Jackie Chan - Actors and Actresses

Pseudonym:

Known to Chinese audiences as Sing Lung, meaning "to become a

dragon."

Nationality:

Hong Kong.

Born:

Chan Kong-Sang in Hong Kong, 7 April 1954.

Education:

Studied at Peking Opera School, Hong Kong, 1961–71.

Career:

1962—screen debut in the Cantonese film

Huang Tian Ba

, subsequently appeared as child actor in more than 20 films;

1972–73—worked as film stuntman and martial artist;

1976—contracted as lead actor by Lo Wei Film Company;

1978—first real success with two films for Ng See-Yuen's

Seasonal Film Corporation; 1979—directed himself for the first time

in

The Fearless Hyena

; 1980—made first film for major Golden Harvest company;

mid-1980s—co-founder, Golden Way production company;

1995—received first widespread North American attention with

Rumble in the Bronx

.

Films as Actor: (films as child actor not included)

- 1971

-

Little Tiger from Canton

- 1973

-

Enter the Dragon ( The Deadly Three ) (Clouse)

- 1975

-

Countdown in Kung Fu ( Hand of Death ) (Woo)

- 1976

-

Xin Ching-Wu Men ( New Fist of Fury ) (Lo Wei) (as Ai Long); Shaolin Wooden Men ( 36 Wooden Men ; Shaolin Chamber of Death ) (Ch'en Chih-Hua and Lo Wei); The Killer Meteors (Lo Wei)

- 1977

-

Snake and Crane Arts of Shaolin (Ch'en Chih-Hua)

- 1978

-

To Kill with Intrigue (Lo Wei); Magnificent Bodyguards (Lo Wei); Snake in the Eagle's Shadow ( The Eagle's Shadow ) (Yuen Woo-ping); Spiritual Kung-Fu ( Karate Ghostbuster ) (Lo Wei)

- 1979

-

Dragon Fist ( In Eagle Dragon Fist ) (Lo Wei); Drunken Master ( Drunken Monkey in a Tiger's Eye ; The Story of Drunken Master ) (Yuen Woo-ping) (as Huang Fei-hong)

- 1980

-

The Big Brawl ( Battle Creek Brawl ) (Clouse) (as Jerry); Half a Loaf of Kung Fu (Ch'en Chi-Hua) (+ martial arts director)

- 1981

-

The Cannonball Run (Needham) (as Subaru driver no. 1); Snake Fist Fighter

- 1983

-

Winners and Sinners (Samo Hung); The Fearless Hyena: Part 2 (Chuen Chan)

- 1984

-

Cannonball Run 2 (Needham) (as Jackie); Meals on Wheels (Samo Hung); Eagle's Shadow (Yuen Woo-ping)

- 1985

-

My Lucky Stars (Samo Hung) (as Muscles); Twinkle, Twinkle, Lucky Stars (Samo Hung); First Mission ; The Protector (Glickenhaus) (as Billy Wong); Ninja Thunderbolt (Ho)

- 1986

-

Heart of the Dragon ( The First Mission ) (Samo Hung)

- 1987

-

Dragons Forever (Samo Hung); Fist of Death

- 1990

-

The Deadliest Art: The Best of the Martial Arts Films (Weintraub—compilation)

- 1992

-

City Hunter (Jing Wong) (as Ryu Saeba); Supercop: Police Story III (Stanley Tong) (as Chan Chia-chu); Twin Dragons (Ringo Lam and Hark Tsui) (as John Ma/Boomer)

- 1993

-

Police Story 4: Project S ( Once a Cop ; Project S ; Supercop 2 ) (Stanley Tong); Crime Story (Kirk Wong) (as Inspector Eddie Chan)

- 1995

-

Hong Faan Kui ( Rumble in the Bronx ) (Stanley Tong) (as Ah Keung, + martial arts director); Thunderbolt

- 1996

-

Rumble in the Bronx (Tong) (as Keung); Supercop 3 (Tong) (as Detective Kevin Chan/Fu Sheng)

- 1998

-

Rush Hour (Ratner) (as Detective Inspector Lee)

- 1999

-

Gorgeous (Kok) (as C.N. Chan); The King of Comedy (Chow, Lee); Tejing xinrenlei (Chan)

- 2000

-

Shanghai Noon (Dey) (as Chong Wang)

Films as Actor and Director:

- 1979

-

Siukun gwaitsiu ( The Fearless Hyena ) (co-d)

- 1980

-

Sidai cheutma ( The Young Master ) (+ co-sc)

- 1982

-

Lung siuye ( Dragon Lord ; Young Master in Love ) (+ co-sc, martial arts choreographer)

- 1983

-

A gaiwak ( Project A ) (as Dragon Ma, + co-sc)

- 1985

-

Gingchat gusi ( Police Story ; Police Force ; Jackie Chan's Police Story ; Jackie Chan's Police Force ) (+ co-sc)

- 1986

-

Lunghing fudai ( The Armour of God ) (+ co-sc)

- 1987

-

A gaiwatsuktsap ( Project A: Part II ) (+ co-sc)

- 1988

-

Gingchat gusi tsuktsap ( Police Story Part II ) (+ co-sc)

- 1989

-

Keitsik ( Miracle ; Black Dragon ; Miracles: The Canton Godfather ; Mr. Canton and Lady Rose ) (as Kuo Cheng-wah/Mr. Canton, + co-sc)

- 1990

-

Lunghing fudai tsuktsap ( The Armour of God II: Operation Condor ) (as Jackie/"Condor," + sc); Island on Fire ( Island of Fire ; The Prisoner )

- 1994

-

Tsui Kun II ( Drunken Master II ) (as Huang Fei-hong)

Publications

By CHAN: articles—

Interview with Tony Rayns and C. Tesson, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), September 1984.

"Jackie Chan, American Action Hero?," interview with Jaime Wolf, in New York Times Magazine , 21 January 1996.

Interview with Michael Kitson, in Cinema Papers (Abbotsford), June 1996.

On CHAN: book—

Rayns, Tony, The Mind Is a Muscle: An Appreciation of Jackie Chan , London, 1987.

On CHAN: articles—

Film Review (London), November 1980.

Ciné Revue (Paris), November 1987.

Kehr, Dave, "Chan Can Do," in Film Comment (New York), May/June 1988.

"Jackie Chan's Big Dilemma: How Long Can He Keep It Up?," in Variety (New York), 1 February 1989.

"Hong Kong Focus," in London Film Festival Programme , 1990.

Ingram, Bruce, "Fast-Moving Jackie Chan's Slow on the Set," in Variety (New York), 18 March 1991.

Elley, Derek, "More Than 'The Next Bruce Lee'," Variety (New York), 23 January 1995.

Corliss, Richard, "Jackie Can!," in Time (New York), 13 February 1995.

Dannen, Fredric, "Hong Kong Babylon," in New Yorker , 7 August 1995.

Straus, Neil, "Higher Style from Hong Kong's Masters," in New York Times , 18 February 1996.

Gallagher, Mark, "Masculinity in Translation: Jackie Chan's Transcultural Star Text," in Velvet Light Trap (Austin), Spring 1997.

* * *

Jackie Chan emerged out of the ranks of martial arts stuntmen and bit players in the mid-1970s as the most talented of those hoping for the international megastardom Bruce Lee had achieved before his death in 1973. In 1976, Lo Wei introduced Chan in a sequel to one of Lee's more popular films, Fist of Fury ( The Chinese Connection ), called New Fist of Fury , in which Chan imitates Lee's fighting style for the most part. Throughout his career, Chan has been haunted by comparisons with Lee. Despite his huge popularity in Asia, evidenced by the box-office records films such as Police Story and Project A: Part II have broken, Chan still aspires to break into the European and American market the way Lee was able to with his Enter the Dragon . To date, Chan's English-language vehicles, The Big Brawl and The Protector , have failed to appeal to most audiences in the West, and Chan is perhaps still most often recognized outside of Asia from his cameo role as the comic Chinese racer in The Cannonball Run series. In 1995, he makes another attempt at winning the American audience with Rumble in the Bronx , filmed "on location" in Vancouver. Although Chan has enjoyed a certain amount of critical attention since his films have been hailed at several international festivals as artistic "masterpieces," popular appeal, outside the Asian community, eludes him.

Comparisons to Lee and failure to win over the Western mass audience are both understandable and unfortunate. Although publicized as a "new Bruce Lee" and encouraged to imitate Lee very early in his film career, Chan, in fact, can best be appreciated as Lee's polar opposite in terms of performance persona and martial arts style. Whereas Lee was fascinated by Western boxing, Philippine stick fighting, and European fencing, which all became part of his very eclectic style, Chan has stuck more to the acrobatic movements associated with the traditional Chinese opera he studied as a young man. A significant part of this involves comic pantomime, and, unlike the more serious and intense Lee, who only occasionally threw in a humorous bit for comic relief, Chan excels at the lighter aspects of the operatic tradition in which his martial skills are rooted. This gift for both acrobatics and comedy has led some critics to compare Chan to Harold Lloyd or Buster Keaton. Conscious of the comparison, Chan has recreated Lloyd's daredevil clock tower stunt and Keaton's infamous falling house stunt in his own films ( Project A: Parts I and II ). Like his silent Hollywood film heroes, Chan prides himself on doing his own stunts, and he has had a number of brushes with death as a result (the most serious a head injury when filming Armour of God ). In the closing credits of his more recent films, outtakes show the bloody results of failed stunts, adding an element of machismo to his star persona missing from the insouciant characters he typically portrays.

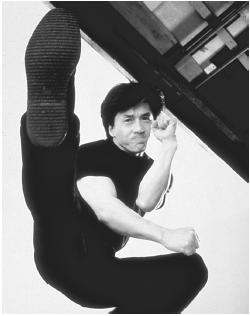

With his wide, almost bulbous nose, sparkling eyes and mischievous smile, Chan's boyish ebullience and remarkable physical prowess seem best put to use in the costume martial arts comedies he made in the late 1970s and early 1980s. During this phase of his career, Chan began to choreograph his own fighting, act as martial arts instructor, and, eventually, direct his own features. As a result, a characteristic Chan star persona really began to emerge, displaying Chan's acrobatic and martial skills to their best advantage.

In most of these films, Chan plays reluctant students who excel at kung fu in spite of themselves. With the exception of Dragon Lord , they all feature scenes that display Chan's physical prowess in training as well as combat. The Chan character is repeatedly tortured by eccentric masters (exemplified by the "drunken master" played by Simon Yuen in Drunken Master and Snake in the Eagle's Shadow ), who casually drink or smoke while Chan sweats blood and plots to escape from kung-fu practice. Set in the past, all these films make use of traditional costumes and weaponry as well as such Chinese arts as lion dancing and calligraphy, and allude to (indeed mildly satirize) established Chinese customs and institutions. In Drunken Master , for example, Chan portrays a young, impudent and impulsive Huang Fei-hong, in sharp contrast to Jet Li's more sober portrayal of the same folk hero in the Once upon a Time in China series. Scenes with expressly Chinese content, however, might explain the cool reception Chan has been given outside the Asian community in the West.

Chan's most recent films mark a significant break with his earlier successes. These later films are set in the present or the more recent past. Unlike the earlier films which delight in Chinese traditions, archaic weaponry, and the arcane aspects of Chinese kung fu, these films have a more Western orientation with gun play, automobile chases, shopping malls, cops, and gangsters replacing rival kung-fu schools, drunken masters, and operatic swordplay. Although Chan continues to play an affable hero, more attention is given to the action-adventure aspects of the plot and to the spectacular, often noncombative stunts than to Chinese martial artistry or acrobatics. No longer the troublesome pupil, Chan has matured into Asia's best-loved comic action hero.

With his own production unit at Hong Kong's Golden Harvest studios, Chan has artistic and a great deal of economic control over his current projects. More than just a kung-fu superstar, Chan has also become a shrewd film producer and promoter. His recent films place Hong Kong and its citizens on the world stage, as players in their own right, with an identity separate from mainland China. In City Hunter , Chan plays a Japanese detective, partly as a tribute to his loyal Japanese fans and partly as a means of looking beyond the confines of Hong Kong. As Rumble in the Bronx brings him back to North America, Chan embodies the fantasy of the Chinese global citizen, acting outside the strictures of a vacillating national identity.

—Gina Marchetti

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: