Tom Hanks - Actors and Actresses

Nationality: American. Born: Concord, California, 9 July 1956. Education: Attended California State University, Sacramento. Family: Married 1) Samantha Lewes, 1978 (divorced 1985), two children; 2) the actress Rita Wilson, 1988, sons: Chester, Truman Theodore. Career: Intern with the Great Lakes Shakespeare Festival, Cleveland, Ohio, and actor with the Riverside Shakespeare Company, New York City; 1980—film debut in He Knows You're Alone ; TV work includes Bosom Buddies , 1980–82, Happy Days , 1982, and Family Ties , 1983–84. Awards: Best Actor Award, Los Angeles Film Critics, for Big and Punchline , 1988; Best Actor Academy Awards, for Philadelphia , 1993, and Forrest Gump , 1994. Agent: c/o Creative Artists Agency, 9830 Wilshire Blvd., Beverly Hills, CA 90212, U.S.A.

Films as Actor:

- 1980

-

He Knows You're Alone (Mastrioianni) (as Elliot)

- 1982

-

Mazes and Monsters (Stern—for TV)

- 1984

-

Splash (Ron Howard) (as Allan Bauer); Bachelor Party (Israel) (as Rick Gasko); The Dollmaker (Petrie—for TV)

- 1985

-

The Man with One Red Shoe (Dragoti) (as Richard); Volunteers (Meyer) (as Lawrence Bourne III)

- 1986

-

The Money Pit (Benjamin) (as Walter Fielding); Nothing in Common (Garry Marshall) (as David Basner); Everytime We Say Goodbye (Mizrahi) (as David)

- 1987

-

Dragnet (Mankiewicz) (as Pep Streebek)

- 1988

-

Big (Penny Marshall) (as Josh Baskin); Punchline (Seltzer) (as Steven Gold)

- 1989

-

The 'Burbs (Dante) (as Ray Peterson); Turner and Hooch (Spottiswoode) (as Scott Turner)

- 1990

-

The Bonfire of the Vanities (De Palma) (as Sherman McCoy); Joe versus the Volcano (Shanley) (as Joe Banks)

- 1992

-

Radio Flyer (Donner) (as narrator); A League of Their Own (Penny Marshall) (as Jimmy Dugan)

- 1993

-

Sleepless in Seattle (Ephron) (as Sam Baldwin); Philadelphia (Jonathan Demme) (as Andrew Beckett)

- 1994

-

Forrest Gump (Zemeckis) (title role)

- 1995

-

Apollo 13 (Ron Howard) (as Jim Lovell); Toy Story (Lasseter) (as voice of Woody); The Celluoid Closet (Epstein and Friedman—doc) (as interviewee)

- 1997

-

I Am Your Child (doc) (Reiner—for TV)

- 1998

-

From the Earth to the Moon (Carson, Field—mini) (as Jean-Luc Despont); Saving Private Ryan (Spielberg) (as Captain John Miller); You've Got Mail (Ephron) (as Joe Fox III)

- 1999

-

Toy Story 2 (Brannon, Lasseter) (as voice of Woody); The Green Mile (Darabont) (as Paul Edgecomb)

Film as Director:

- 1989

-

Tales from the Crypt

- 1993

-

A League of Their Own: "The Monkey's Curse " (for TV); Fallen Angels: "I'll Be Waiting" (for TV)

- 1996

-

That Thing You Do (+ ro, sc)

- 1998

-

From the Earth to the Moon, Part 1 (for TV + pr +sc on parts 6,7,11,12)

Publications

By HANKS: articles—

Interview, in Films (London), July 1984.

Interview, in Photoplay (London), September 1984.

Interview, in Time Out (London), 26 October 1988.

Interview with Beverly Walker, in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1989.

"An Interview with Geena Davis," in Interview (New York), March 1992.

Interview with Brendan Lemon, in Interview (New York), December 1993.

"A Philadelphia Story," interview with Brad Gooch, in Advocate , 14 December 1993.

"Peaking Tom," interview with Brian D. Johnson, in Maclean's (Toronto), 11 July 1994.

"I Wonder, How Did This Happen To Me?" interview with Andrew Duncan, in Radio Times (London), 16 September 1995.

"What on Earth Do I Do Next?" interview with Jane E. Dickson, in Radio Times (London), 1 February 1997.

"Hanks for the Memories," interview with Trevor Johnston, in Time Out (London), 22 January 1997.

On HANKS: books—

Trakin, Roy, Tom Hanks: Journey to Stardom , 1987; rev. ed.1995.

Salamon, Julie, The Devil's Candy: "The Bonfire of the Vanities" Goes to Hollywood , Boston, 1991.

Wallner, Rosemary, Tom Hanks: Academy Award-Winning Actor , Edina, Minnesota, 1994.

Pfeiffer, Lee, The Films of Tom Hanks , Secaucus, New Jersey, 1996.

Quinlan, David, Tom Hanks: a Career in Orbit , B. T. Batsford Limited, 1998.

McAvoy, Jim, Tom Hanks , Broomall, 1999.

On HANKS: articles—

Current Biography 1989 , New York, 1989.

Troy, C., "It's a Cool Gig," in American Film (Hollywood), April 1990.

DeNicolo, David, "Right behind Mr. Nice Guy Lurks an Edgy Tom Hanks," in New York Times , 20 June 1993.

Conant, Jennet, "Tom Hanks Wipes That Grin off His Face," in Esquire (New York), December 1993.

Andrew, Geoff & Floyd, Nigel, "No Hanky Panky: The 'Philadelphia' Story/Straight Acting," in Time Out (London), 23 February 1994.

Ebert, Roger, "Thanks, Hanks," in Playboy (Chicago), December 1994.

* * *

It is a cliché of press-agentry that comedians are always looking for a "stretch," seeking to redefine themselves as serious actors. Much rarer is the remarkable transformation of Tom Hanks from moderately successful television sitcom co-star to one of America's most beloved actors, matching only Spencer Tracy in winning two consecutive Oscars for Best Actor. Having firmly established his own comic persona, Hanks went on to roles that seemed to play deliberately against his type, or used it as a subtext, while in certain recent roles, notably his kindly country prison guard in The Green Mile, he seems to have abandoned it altogether. Less a comedian with acting ability than an actor with a wry sensibility that lends itself to comic roles, Hanks managed better than any comic actor of his generation to make a transition to dramatic leads.

Looking back on the 1984 Splash , which gave the young actor his first leading role and immediate stardom, one finds that he does not give an "apprentice" performance, one that affords mere glimpses of his future screen persona, but rather a fullblown Tom Hanks performance. Already in evidence is the distinctive combination of shyness and a cool knowingness. He makes full use of his slightly pudgy boyish face with its crooked, impish smile; in particular he has mastered a great variety of facial reactions to others' bizarre or obnoxious behavior (a brother's outrageous schemes, a scientist's rudeness, a mermaid eating a lobster, shell and all), as if he were engaged in an inner dialogue with himself. In the scene where the mermaid rejects the youth's marriage proposal, one sees a glimpse too of the petulant sarcastic anger that he will display more prominently in dramatic roles in Nothing in Common and Punchline . He is often funniest when his character is unhappiest, as in the wedding scene, where the guests' queries about his absent fiancee (who has just rejected him) provoke increasingly exasperated reactions.

Splash also establishes a favorite situation for a Tom Hanks comedy: a relatively normal, reasonably sophisticated person reacting with surprisingly little hysteria to the most preposterous situations: here a mermaid, later a collapsing house, spooky neighbors, an insufferable dog, a human sacrifice to a volcano, or the vicissitudes of the Peace Corps. With the special exception of Big , the light comedies do not develop the Hanks persona so much as reprise it; indeed, they offer only a pale reflection of the original when the writing and direction are weak, as in The 'Burbs .

Hanks's boyish looks and, sometimes, air of mischief suited him for roles in which an immature youth, not so much callow as heedless or self-centered, must grow up. In Volunteers the involuntary Peace Corps hero must (however perfunctorily) shape up; in Nothing in Common a self-characterized "childish, selfish" advertising executive has not yet become a "bona fide adult" because his estrangement from his parents has left him emotionally arrested; and in Punchline , a would-be comedian is (again) estranged from his father and capable only of an Oedipal crush upon an older woman. Even in Sleepless in Seattle , where the older Hanks is a widower with a small son and none of the impishness, the role calls for him to replay those anxious boyish days of having to learn the "rules" for dating all over again.

The maturity issue is treated most interestingly in Big , which critiques the perennial appeal of the American child-man to American women and to popular film audiences (while capitalizing upon that appeal at the same time). To portray a 13-year-old inside a man's body Hanks must eliminate the hip side of his persona altogether, but a surprising amount of the Hanks manner remains: the shyness, the wary alertness, the moments of exuberance and playfulness. Perhaps the really new dimension in this role is the occasional moment of naked vulnerability, notably in the moving scene of the man-child's first night in a sinister hotel.

Released the same year as Big , Punchline features one of Hanks's most complex dramatic performances. Here, besides successfully handling several virtuoso scenes, such as the on-stage emotional breakdown and the comic-pathetic "Singin' in the Rain" number, Hanks is able to make something consistent, scene by scene, of an extremely mercurial character, not to mention creating some sympathy for a frequently rude egotist. Of his performance as a gay lawyer with AIDS in the didactic Philadelphia , the cynical could argue that much of his physical decline is accomplished with makeup, and that much of the power of his "Maria Callas" monologue, virtually an aria in itself, comes from the diva's own voice and the director's near-expressionistic lighting and high camera angles. But certainly the actor must be credited for conveying the character's moments of overwhelming terror, determination to achieve justice, sardonic bitterness, and, with a touch of the Hanks boyish smile in the scene on the witness stand, an idealistic love for the law. Of his other pre- Gump dramatic roles, only in The Bonfire of the Vanities , valiantly sporting an upper-crust accent but sabotaged by an ill-conceived script (and incidentally by his own nonpatrician looks), does Hanks fail to create a coherent character, although he at least gets to do a splendid display of outrage in the scene where he drives away the party guests.

As for his incarnation of the "simpleton" Forrest Gump, it must suffice to say that behind the American-Gothic frown and near-monotone delivery, Hanks finds a remarkably subtle range of voice tones and glances to suggest an inner life for a fantasy character—one who is already "old" in suffering but never crushed by sorrow, an Ancient Mariner with a story to tell America but no guilt to expiate. The weight behind each reiteration of "That's all I have to say about that"; the merest hint of knowing disapproval in references to Richard Nixon; the rare outbursts of glee in reunions with Lieutenant Dan: these and countless other details add shadings to what could have been a stiffly allegorical figure.

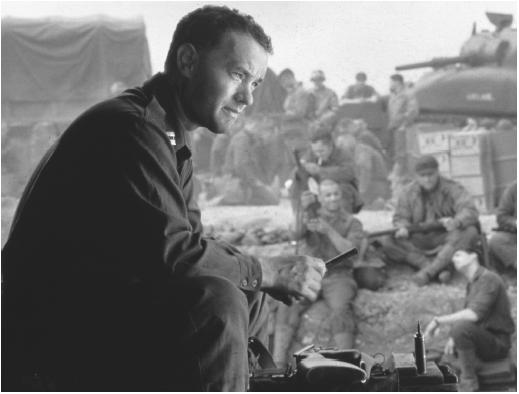

It is indicative of Hanks' post- Gump status as an all-American icon that his decent, solid performance as a decent, solid astronaut in Apollo 13 was widely touted as deserving yet another Oscar, and he did receive a nomination for what might be called a study in heroic decency, in Saving Private Ryan. It is instructive to compare his performance with that of, say, Lee Marvin in Samuel Fuller's The Big Red One (1980), another WWII story of a man leading a small group of soldiers through combat. Marvin's grizzled veteran, equally decent but the essence of the tough Sarge, is worlds (but really just a generation) away from Hanks' and the screenwriters' dryly ironic but close-to-cracking Captain Miller. Firm enough to be plausibly in command, sensitive enough to break down weeping when the other soldiers can't see him, capable of outrage when one of his men disobeys orders to "rescue" a little girl, and also of ironic banter with his men, Miller is one of Hanks' richer roles. It allows him big speeches, as when he tries to justify the number of men he has lost under his command, and subtle moments, as when—in quite different ways, with different inflections—he tells two different Pvt. Ryans (the first the wrong man) that all of his brothers have been lost in action. When the first Ryan realizes that a mistake has been made, and tearfully says, "Well, does that mean that my brothers are OK?" Miller's reply, "Yeah, I'm sure they're fine," is pure Hanks, without breaking character, in its irony verging upon sarcasm and disgust over the whole situation.

Hanks' only altogether "light" roles in recent films have been the voice of Woody in the Toy Story films. Of course, You've Got Mail is a romantic comedy, but rather than replay the character in Sleepless in Seattle , his previous outing with Meg Ryan, he is refreshingly (in the character's own words) an arrogant, spiteful and condescending "Mr. Nasty," a megabookstore entrepreneur who relishes the opportunity to drive Ryan's genteel neighborhood shop out of business. The plot calls for the character's underlying decency to surface in the anonymous e-mail friendship he shares with Ryan, and for a change of heart after his initial outrage that his electronic penpal is his insufferable business foe; but fortunately Hanks never turns smarmy, and never calls upon his old boyish cuteness, when his character becomes a pursuing lover. (He also never reminds us of James Stewart, another all-American icon, who played the original role in The Shop Around The Corner in 1940.) Indeed, he remains a little snotty even to the end.

While convincingly saintly and low-key American heroes are always in short supply on the screen, one can hope that Hanks doesn't choose too many such roles. He remains most memorable when he takes a risk in parts with curious mixtures of comedy and drama, like his comedian in Punchline , his Gump, or—a true character role—his drunken baseball coach in A League of Their Own.

—Joseph Milicia

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: