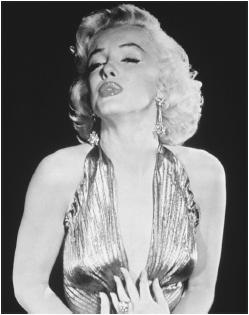

Marilyn Monroe - Actors and Actresses

Nationality:

American.

Born:

Norma Jean Mortenson (or Baker) in Los Angeles, California, 1 June 1926.

Education:

Studied acting at Actors Lab in Los Angeles and Actors Studio in New

York.

Family:

Married 1) James Dougherty, 1942 (divorced 1948); 2) the baseball player

Joe DiMaggio, 1954 (divorced 1954); 3) the writer Arthur Miller, 1956

(divorced 1961).

Career:

During World War II worked in aircraft factory, then began modeling;

1946—short contract with 20th Century-Fox; 1948—film debut

in

Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay!

; 1950—success in films

The Asphalt Jungle

and

All about Eve

led to long-term contract with Fox.

Died:

Probable suicide, 5 August 1962.

Films as Actress:

- 1948

-

Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! ( Summer Lightning ) (Herbert) (as extra); Dangerous Years (Pierson) (as Evie); Ladies of the Chorus (Karlson) (as Peggy Martin)

- 1949

-

Love Happy (Miller) (as extra)

- 1950

-

A Ticket to Tomahawk (Sale) (as Clara); The Asphalt Jungle (Huston) (as Angela Phinlay); All about Eve (Joseph L. Mankiewicz) (as Miss Caswell); The Fireball ( The Challenge ) (Garnett) (as Polly); Right Cross (John Sturges) (as girl at nightclub)

- 1951

-

Home Town Story (Pierson) (as Miss Martin); As Young as You Feel (Harmon Jones) (as Harriet); Love Nest (Joseph M. Newman) (as Roberta Stevens); Let's Make It Legal (Sale) (as Joyce)

- 1952

-

Clash by Night (Fritz Lang) (as Peggy); We're Not Married (Goulding) (as Annabel Norris); Don't Bother to Knock (Roy Ward Baker) (as Nell); Monkey Business (Hawks) (as Lois Laurel); "The Cop and the Anthem" ep. of O. Henry's Full House ( Full House ) (Koster) (as streetwalker)

- 1953

-

Niagara (Hathaway) (as Rose Loomis); Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Hawks) (as Lorelei Lee); How to Marry a Millionaire (Negulesco) (as Pola Debevoise)

- 1954

-

River of No Return (Preminger) (as Kay Weston); There's No Business Like Show Business (Walter Lang) (as Vicky)

- 1955

-

The Seven Year Itch (Wilder) (as the Girl)

- 1956

-

Bus Stop (Logan) (as Cherie)

- 1957

-

The Prince and the Showgirl (Olivier) (as Elsie Marina)

- 1959

-

Some Like It Hot (Wilder) (as Sugar Kane)

- 1960

-

Let's Make Love (Cukor) (as Amanda Dell)

- 1961

-

The Misfits (Huston) (as Roslyn Tabor)

Publications

By MONROE: books—

My Story , New York, 1974.

Marilyn in Her Own Words , New York, 1983; as Marilyn on Marilyn , London, 1983.

A Never-Ending Dream , edited by Guus Luijters, New York, 1986.

On MONROE: books—

Martin, Pete, Will Acting Spoil Marilyn Monroe? , New York, 1956.

Zolotow, Maurice, Marilyn Monroe , New York, 1960; rev. ed., 1990.

Carpozi, George Jr., Marilyn Monroe: "Her Own Story," New York, 1961.

Violations of the Child: Marilyn Monroe , by "Her Psychiatrist Friend," New York, 1962.

The Films of Marilyn Monroe , edited by Michael Conway and Mark Ricci, New York, 1964.

Hoyt, Edwin, Marilyn: The Tragic Years , New York, 1965.

Guiles, Fred, Norma Jean: The Life of Marilyn Monroe , New York, 1969.

Wagenknecht, Edward, Marilyn Monroe: A Composite View , Philadelphia, 1969.

Huston, John, An Open Book , New York, 1972.

Mailer, Norman, Marilyn , New York, 1973.

Mellen, Joan, Marilyn Monroe , New York, 1973.

Rosen, Marjorie, Popcorn Venus , New York, 1973.

Kobal, John, Marilyn Monroe: A Life on Film , New York, 1974.

Murray, Eunice, with Rose Shade, Marilyn: The Last Months , New York, 1975.

Sciacca, Tony, Who Killed Marilyn? , New York, 1976.

Weatherby, W. J., Conversations with Marilyn , New York, 1976.

Pepitone, Lena, and William Stadiem, Marilyn Monroe Confidential: An Intimate Personal Account , New York, 1979.

Dyer, Richard, editor, Marilyn Monroe , London, 1980.

Mailer, Norman, Of Women and Their Elegance , New York, 1981.

Anderson, Janice, Marilyn Monroe , New York, 1983.

Summers, Anthony, Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe , London, 1985.

Kahn, Roger, Joe and Marilyn: A Memory of Love , New York, 1986.

Rollyson, Carl E., Marilyn Monroe: A Life of the Actress , Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1986.

Steinem, Gloria, and George Barris, Marilyn , New York, 1986.

Arnold, Eve, Marilyn Monroe: An Appreciation , London, 1987.

Crown, Lawrence, Marilyn at Twentieth Century-Fox , New York, 1987.

Dyer, Richard, Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society , London, 1987.

Miller, Arthur, Timebends , New York, 1987.

Shevey, Sandra, The Marilyn Scandal: Her True Life Revealed by Those Who Knew Her , London, 1987.

McCann, Graham, Marilyn Monroe , Cambridge, 1988.

Mills, Bart, Marilyn on Location , London, 1989.

Schirmer, Lothar, Marilyn Monroe and the Camera , London, 1989.

Marriott, John, Marilyn Monroe , Philadelphia, 1990.

Haspiel, James, Marilyn: The Ultimate Look at the Legend , London, 1991.

Brown, Peter H., Marilyn: The Last Take , New York, 1992.

Strasberg, Susan, Marilyn and Me: Sisters, Rivals, Friends , New York, 1992.

Wayne, Jane Ellen, Marilyn's Men: The Private Life of Marilyn , New York, 1992.

Gregory, Adela, Crypt 33: The Saga of Marilyn Monroe—The Final Word , Secaucus, New Jersey, 1993.

Guiles, Fred Lawrence, Norma Jean: The Life of Marilyn Monroe , New York, 1993.

Spoto, Donald, Marilyn Monroe: The Biography , New York, 1993.

Miracle, Berniece Baker, and Mona Rae Miracle, My Sister Marilyn: A Memoir of Marilyn Monroe , Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1994.

Baty, S. Paige, American Monroe: The Making of a Body Politic , Berkeley, 1995.

Lefkowitz, Frances, Marilyn Monroe , New York, 1995.

Paris, Yvette, Dying to Be Marilyn , Fort Collins, 1996.

Leaming, Barbara, Marilyn Monroe , New York, 1998.

Wolfe, Donald H., The Last Days of Marilyn Munroe , New York, 1998.

Ajlouny, Joseph, Marilyn, Norma Jean & Me , Farmington Hills, 1999.

Karanikas Harvey, Diana, Marilyn , New York, 1999.

Kidder, Clark, Marilyn Monroe: Cover-To-Cover , Iola, 1999.

Levinson, Robert S., The Elvis & Marilyn Affair , New York, 1999.

Victor, Adam, Marilyn: The Encyclopedia , New York, 1999.

On MONROE: articles—

Baker, P., "The Monroe Doctrine," in Films and Filming (London), September 1956.

Current Biography 1959 , New York, 1959.

Obituary in New York Times , 6 August 1962.

Odets, Clifford, "To Whom It May Concern: Marilyn Monroe," in Show (Hollywood), October 1962.

Roman, Robert, "Marilyn Monroe," in Films in Review (New York), October 1962.

Fenin, G., "M.M.," in Films and Filming (London), January 1963.

Durgnat, Raymond, "Myth: Marilyn Monroe," in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1974.

"Marilyn Monroe Issue" of Cinéma d'aujourd'hui (Paris), March/April 1975.

Haspiel, J. R., "Marilyn Monroe: The Starlet Days," in Films in Review (New York), June/July 1975.

Stuart, A., "Reflection of Marilyn Monroe in the Last Fifties Picture Show," in Films and Filming (London), July 1975.

Haspiel, J. R., "That Marilyn Monroe Dress," in Films in Review (New York), June/July 1980.

Gilliatt, Penelope, "Marilyn Monroe," in The Movie Star , edited by Elisabeth Weis, New York, 1981.

Stenn, D., "Marilyn Inc.," and David Thomson, "Baby Go Boom!," in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1982.

Belmont, Georges, "Souvenirs d'Hollywood," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), July/August 1987.

Minifie, D., "Marilyn Monroe," in Films and Filming (London), August 1987.

Haun, H., "Marilyn Monroe," in Films in Review (New York), November 1987.

Lexton, Maria, "Book of Revelation," in Time Out (London), 8 July 1992.

Legrand, Gérard, "The Irresistible Marilyn," in Radio Times (London), 11 July 1992.

Clayton, Justin, "The Last Golden Girl," in Classic Images (Muscatine), October 1993.

Hoberman, J., "Korea and a Career," in Artforum , January 1994.

Spoto, D., "Marilyn Monroe," in Architectural Digest (Los Angeles), April 1994.

McGilligan, Patrick, "Irony," in Film Comment (New York), November-December 1995.

Norman, Barry, in Radio Times (London), 11 May 1996.

Golden, Eve, "Marilyn Monroe at 70: A Reappraisal," in Classic Images (Muscatine), June 1996.

Savage, S., "Evelyn Nesbit and the Film(ed) Histories of the Thaw-White Scandal," in Film History (London), no. 2, 1996.

Cardiff, J., "Magic Marilyn," in Eyepiece (Greenford), no. 4, 1997.

Jacobowitz, F., and R. Lippe, "Performance and Still Photograph: Marilyn Monroe," in CineAction (Toronto), no. 44, 1997.

On MONROE: films—

Marilyn , documentary, narrated by Rock Hudson, 1963.

Marilyn Monroe, Life Story of America's Mystery Mistress , documentary, 1963.

Marilyn: The Untold Story , directed for television by John Flynn, Jack Arnold, and Lawrence Schiller, 1980.

Marilyn and the Kennedys , documentary for television, 1985.

Marilyn Monroe: Beyond the Legend , documentary, 1985.

Marilyn: Say Goodbye to the President , documentary, 1985.

Marilyn Monroe , documentary, 1990.

Marilyn Monroe: The Last Word , documentary, 1990.

Marilyn Monroe: The Woman behind the Myth , documentary, 1990.

Marilyn and Me , directed for television by John Patterson, 1991.

Marilyn Monroe: The Marilyn Files , documentary, 1991.

Norma Jean & Marilyn , television movie, 1996.

* * *

More pages have been written about Marilyn Monroe than any other movie star. She has inspired all sorts of fellow artists, from novelists to painters to rock songwriters. In 1996, 34 years after Monroe's death (at age 36), HBO brought Oscar winner Mira Sorvino to the small screen in yet another retelling of Monroe's life. Representations of femininity, sexuality, and American ambition created by and around Monroe continue to fascinate, indicating that tensions among these factors continue to exist.

To some she was a gifted comedienne, to others a sexual joke, but there is no doubt that Marilyn Monroe staked a claim for herself in film history as the quintessential "dumb" blond, the biggest of the blond bombshells. She had, according to Billy Wilder, "flesh impact." And her face was her fortune as much as her voluptuous figure (Wilder again): "The luminosity of that face! There has never been a woman with such voltage on the screen, with the exception of Garbo."

Monroe's appeal lay in more than her physical attributes. Another director, Joshua Logan, described her as "naive about herself and touching, rather like a little frightened animal." Lee Strasberg saw "a combination of wistfulness, radiance, yearning [that] set her apart and [made] everyone wish to . . . share in the childish naivete which was at once so shy and yet so vibrant." Or, in the words given to Cary Grant and Ginger Rogers in Monroe's film Monkey Business , she was "half child, but not the half that shows."

Monroe's triumphs in projecting the woman-as-child arose in part from the traumas of her personal life. Orphaned as a child by her father's desertion and mother's insanity, brought up in an orphanage and foster homes, and married at 16 to a boy of 20, she developed, according to critic Molly Haskell, a "painful, naked, and embarrassing need for love." Moreover, her mother's insanity, and the fact that both her mother's parents had also been committed to institutions, may have deepened fears of abandonment instilled by her childhood experiences. Certainly her genetic heritage did nothing to encourage her to envision a future as a responsible adult.

Yet she was adult enough to work throughout her life to develop her

control over her psycho-physical actor's instrument. Most of all,

Monroe engaged with Constantin Stanislavski's ideas—that an

actor's job is to make every physical move meaningful, to embrace

and embody the world as it is for her, not for

convention—variations of which she studied in the early 1950s with

Michael Chekhov and, more famously, in the mid-1950s with Lee and Paula

Strasberg. To further clarify for herself ways to physicalize her

characters' inner states, Monroe kept with her Mabel Elsworth

Todd's book

The Thinking Body

. Once Monroe had the "handle" for a role or scene, she was,

according to Montgomery Clift, "an incredible person to act with. .

.

. Playing a scene with her . . . was like an escalator. You'd do

something, and she'd catch it and would go like that, just right

up."

Her first films relegated her display of such talents to modeling jobs and acting classes. Under contract at Twentieth Century-Fox in 1946–47, she had bit parts in two forgettable films ( Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! and Dangerous Years ). In 1948 Columbia gave her a six-month contract and an introduction to the studio's head acting teacher Natasha Lytess, a former member of Max Reinhardt's company. Until the mid-1950s, Lytess would be Monroe's personal drama coach and a fixture on her sets. Monroe's official debut was a leading role in a B picture, Ladies of the Chorus . Though she showed promise, it wasn't until her first film for MGM, The Asphalt Jungle , that she made a real impact with both the public and the critics. Small parts in All about Eve and in several B pictures led to more substantial roles in We're Not Married and Monkey Business .

For her biggest role yet, in Don't Bother to Knock , Monroe received mixed reviews playing a psychotic babysitter obsessed with her dead lover. As Carl Rollyson notes, Monroe in this film builds perhaps too obviously upon what her second acting instructor, Stanislavski's associate Michael Chekhov, called "the psychological gesture." Such a keystone gesture—here Monroe's twisting together of her fingers—not only encapsulates a character's mental state but allows changes in it to be revealed over time. Throughout her career, as pinup girl, on-stage USO diva in Korea, and movie star, Monroe can be seen carefully framing her own body—using her hands, arms and hips especially—for maximum emotional resonance. Her appeal as a screen actress and archetypal image rests upon this self-composition more than is commonly acknowledged.

Monroe's first starring role was in Niagara , which elevated her to the ranks of 1953's top-grossing stars. As a faithless wife, she delivered a credible performance while projecting a great deal of sex appeal. Her undulations across some cobblestones represented the longest walk in cinema history—116 feet of film.

Niagara was followed by other rich roles. As Lorelei in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes , she showed she could sing and anchored the first of many delightful production numbers. (These redeemed such lesser films as River of No Return and Let's Make Love .) How to Marry a Millionaire further proved her comic talents. As the innocent myopic Pola Debevoise, a gold digger reluctant to wear glasses, she walked into walls and read books upside down with comic aplomb.

Monroe's next big film was The Seven Year Itch , in which she played a lightly parodic media sex goddess with subtle sensitivity. But by then she was disillusioned with her success and bored with her "dumb blond" image. Wanting to continue her artistic growth as a working actress, she left Hollywood for New York and the Actors Studio. Public reaction was unkind. Life magazine called the move "irrational," and Time found her all wet: "her acting talents, if any, run a needless second" to her truest virtues—"her moist 'come-on' look . . . moist, half-closed eyes and moist, half-opened mouth."

But Monroe spent a year with Lee Strasberg, director of the Actors Studio, learning to tap her own experience to work into her characters. At the Strasbergs' prompting, she entered psychoanalysis to negotiate her new self-knowledge. By the end of the year she had more sophisticated tools for exploring her characters—but she was gradually disintegrating as a person. The ego she had so carefully assembled in her early twenties came unglued in her increasing, drug-fueled fears of something lacking in herself.

Still, Bus Stop , her first film upon returning to Hollywood, was a revelation to the critics: "get set for a surprise. Marilyn Monroe has finally proved herself an actress" (Bosley Crowther, New York Times ). Working for the first time with a southern accent, Monroe caught the delicate balance the script sets between her character's self-image and her limitations, especially in her songs. Critics disagreed over whether Monroe's modulated, realistic portrayal was due to the Strasbergs' influence or to the fact that it was her first role of any depth.

Her next film was made by her own company, which she had set up with Milton Greene. Although she and Laurence Olivier, her co-star and director, delivered good performances in The Prince and the Showgirl , problems between them on the set exacerbated Monroe's growing insecurity and addictions and did little to offset her distress over a troubled third marriage, to playwright Arthur Miller.

Monroe's sex appeal and comic timing were happily arrayed again in Some Like It Hot . But her next film, Let's Make Love , was a critical failure that brought her into an unhappy romance with her co-star, Yves Montand. By the time she did The Misfits (written for her by Miller), although she delivered a multifaceted, poignant performance, her chronic lateness and addiction to alcohol and pills were out of control. These afflictions caused her removal from a subsequent film, Something's Got to Give , and she died two months later of a drug overdose.

Her death was a tragic conclusion to a promising career. According to director John Huston, something disturbing happened to Monroe between The Asphalt Jungle and The Misfits , but it deepened her responses; now her acting came from inside. As a child, Monroe "used to playact all the time. For one thing, it meant I could live in a more interesting world than the one around me." But the magnificent life she brought to the screen finally eluded her in reality.

—Catherine Henry, updated by Susan Knobloch

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: