Eddie Murphy - Actors and Actresses

Nationality: American. Born: Edward Regan Murphy in Brooklyn, New York, 3 April 1961. Education: Attended Roosevelt High School. Family: Married Nicole Mitchell, 1993, children: Bria, Miles Mitchell, Shayne Audra. Career: First public performance at a youth center on Long Island, 1976; regular on Saturday Night Live for NBC TV, 1980–84; film debut in 48 HRS. , 1982; signed multi-film deal with Paramount, 1985; formed own film production company; formed Eddie Murphy Television Enterprises, 1986; directed first film, Harlem Nights , 1989. Address: c/o Eddie Murphy Productions, Inc., 152 West 57th Street, 47th Floor, New York, NY 10019, U.S.A.

Films as Actor:

- 1982

-

48 HRS. (Walter Hill) (as Reggie Hammond)

- 1983

-

Trading Places (Landis) (as Billy Ray Valentine)

- 1984

-

Best Defense (Huyck) (as Landry); Beverly Hills Cop (Brest) (as Axel Foley)

- 1986

-

The Golden Child (Ritchie) (as Chandler Jarrell)

- 1987

-

Beverly Hills Cop II (Tony Scott) (as Axel Foley, + story); Eddie Murphy Raw (concert performance)

- 1988

-

Coming to America (Landis) (as Prince Akeem/Clarence/Saul/Randy Watson, + story)

- 1990

-

Another 48 HRS. (Walter Hill) (as Reggie Hammond)

- 1992

-

The Distinguished Gentleman (Lynn) (as Thomas Jefferson Johnson); Boomerang (Hudlin) (as Marcus Graham, + story)

- 1994

-

Beverly Hills Cop III (Landis) (as Axel Foley)

- 1995

-

Vampire in Brooklyn (Craven) (as Maximillian/Preacher Pauley/Guido, + pr, story)

- 1996

-

The Nutty Professor (Shadyac) (as Sherman Klump/Buddy Love and the Klump Family)

- 1997

-

The Metro (Carter) (as Scott Roper + pr)

- 1998

-

Mulan (Bancroft, Cook) (as voice of Mushu); Doctor Dolittle (Betty Thomas) (as Dr. John Dolittle); Holy Man (Herek) (as G.)

- 1999

-

Life (Ted Demme) (as Rayford Gibson + exec pr); The PJs (Gustafson, series for TV) (as voice of Superintendent Thurgoode Orenthal Stubbs + exec pr); Bowfinger (Oz) (as Kit Ramsey/Jiff Ramsey)

- 2000

-

The Nutty Professor II: The Klumps (Segal) (as Sherman Klump/Buddy Love); Shrek (Adamson/Asbury) (voice)

Film as Actor and Director:

- 1989

-

Harlem Nights (as Quick, + exec pr, sc)

Other Film:

- 1990

-

The Kid Who Loved Christmas (exec pr)

Publications

By MURPHY: articles—

Interviews in Time Out (London), 1 December 1983 and 6 July 1988.

Interview in Jet (Chicago), 18 March 1985.

Interview in Photoplay (London), May 1985.

Interview in Interview (New York), September 1987.

Interview with Bill Zehme, in Rolling Stone (New York), 24 August 1989.

Interview with David Rensin, in Playboy (Chicago), February 1990.

Interview with Walter Leavy, in Ebony (Chicago), June 1994.

"Murphy's Lore," interview with David Eimer, in Time Out (London), 28 August 1996.

"Sex Is Easy to Get: Stand-up Comedy You Have to Work For," interview with Andrew Duncan, in Radio Times (London), 28 September 1996.

On MURPHY: books—

Davis, Judith, The Unofficial Eddie Murphy Scrapbook , New York, 1984.

Ruuth, Marianne, Eddie: Eddie Murphy from A to Z , Los Angeles, 1985.

Koenig, Teresa, Eddie Murphy , Minneapolis, 1985.

Gross, Edward, The Films of Eddie Murphy , Las Vegas, Nevada, 1990.

Wilbourn, Deborah A., Eddie Murphy , New York, 1993.

Sanello, Frank, Eddie Murphy: The Life and Times of a Comic on the Edge , Carol Publishing Group, 1997.

On MURPHY: articles—

Current Biography 1983 , New York, 1983.

Corliss, Richard, "The Good Little Bad Little Boy," in Time (New York), 11 July 1983.

Connelly, Christopher, "Eddie Murphy Leaves Home," in Rolling Stone (New York), 12 April 1984.

Hibbin, S., "Eddie Murphy," in Films and Filming (London), December 1984.

"Inside Moves," in Esquire (New York), January 1985.

Berkoff, Steven, in Time Out (London), 1 February 1985.

Grenier, Richard, "Eddie Murphy, American," in Commentary (New York), March 1985.

Townsend, Robert, "Eddie, the Black Pack and Me," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), December 1987.

Ehrenstein, David, "The Color of Laughter," in American Film (New York), September 1988.

"Three Generations of Black Comedy," in Ebony (Chicago), January 1990.

Schickel, Richard, "In Search of Eddie Murphy: The Gifts that Made Him a Star Have Disappeared into Self-Parody," in Time (New York), 25 June 1990.

Richardson, John H., "Murphy's Law," in Premiere (New York), January 1992.

Richmond, Peter, "Trading Places," in GQ (New York), July 1992.

Stivers, Cyndi, "Murphy's Law," in Premiere (New York), August 1992.

Brennan, J., "Murphy's Cool about Being Top Cat," in Variety (New York), 15 March 1993.

Radio Times (London), 9 July 1994.

Samuels, A. and J. Giles, "The Nutty Career," in Newsweek , 1 July 1996.

Hennessey, K. and E. Bailey, "Look Before You Leap!" in Movieline (Escondido), October 1996.

* * *

Young and ambitious, black comedian Eddie Murphy rose from the ranks of stand-up comedy and television to become one of the top box-office film stars of the 1980s only to see his career and popularity take a precipitous nosedive in the 1990s.

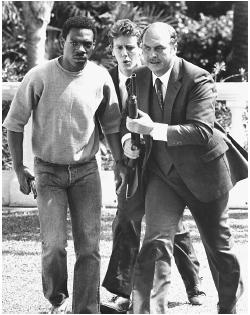

While still a teenager, Murphy began haunting the comedy clubs in New York City, honing his craft at night while attending school during the day. After high school, he was selected to join the cast of Saturday Night Live , the late-night television series that had launched the careers of celebrated comic actors John Belushi, Bill Murray, and Dan Aykroyd. The show offered a forum for Murphy to showcase his talent for mimicry as well as to develop a series of memorable characters, including Gumby, Buckwheat, and Mr. Robinson, which were biting takeoffs on television favorites from the past. A starring role opposite Nick Nolte in the action film 48 HRS. helped to construct his distinctive film persona—that of the sassy, self-confident, often abrasive con artist who is fast on his feet.

From 48 HRS. to Harlem Nights , each of Murphy's roles has made use of this image, even the character of Officer Axel Foley in Beverly Hills Cop (a role originally slated for Sylvester Stallone) and its lackluster sequels, Beverly Hills Cop II and III. Like the fast-talking con-man characters in all of Murphy's films, Axel easily assumes other identities in order to get past some obstacle. Murphy's adeptness at mimicry—whether it is a recognizable character such as Buckwheat or a stereotype such as a fastidious government inspector—is his trademark. His roles emphasize this talent, which places most of his films in the category of star vehicles.

Other aspects of Murphy's comic persona, particularly as displayed in his stand-up routines earlier in his career, include a proclivity toward provocative, masculine humor. His speech is peppered with expletives and street slang, while his self-assured demeanor is assertive. Yet his comedy and his image do not threaten his white audiences. The best of Murphy's humor and the best of his film roles create a tension between the dangerously provocative and the brashly humorous: he makes a potentially volatile joke but tempers the delivery with a wide grin and a unique belly laugh.

Comparisons to Richard Pryor, the biggest black star of the last generation, are inevitable. Though Murphy claims Pryor as a major influence, profound differences mark their comedy styles and personas. Pryor's stand-up routines derive from growing up on society's margins. The characters—winos, junkies, prostitutes—he plays in his routines mirror that society. Murphy grew up in a lower-middle-class neighborhood on Long Island; the primary source for many of his routines and comic impersonations is television. No matter how many four-letter words he uses, Murphy has an immediate bond with mainstream audiences who grew up with the tube.

Toward the end of the 1980s, Murphy experienced a backlash in the media. As occurs to many popular figures who suddenly become superstars, he began to be criticized by a press that had previously been friendly. Reviewers attacked such films as Beverly Hills Cop II and Another 48 HRS. for being uninspired vehicles chosen to cash in on his fame and the success of their forerunners, while stories about his numerous bodyguards, enormous wealth, frequent womanizing, and galloping ego added to the media-based perception that success had gone to his head and altered his personality. This criticism culminated in the beating he took for his vanity production Harlem Nights , an action comedy he wrote, co-produced, directed, and starred in. The film was poorly executed, but reviewers unfairly dismissed Murphy's interest in working behind the camera as the actions of an ego-driven superstar, conveniently forgetting that he had expressed a desire to produce and direct as far back as 1983. Suddenly, Murphy's self-confidence was deemed arrogance; his mainstream appeal was termed "a slick, Hollywood package."

All this negative press had repercussions at the box office. Murphy rebounded slightly with The Distinguished Gentleman in which he took his con-artist persona of the Beverly Hills Cop I and II , 48 HRS. , Another 48 HRS. , and other films to Washington, D.C., to cash in on the gravy train as a freewheeling, wheeler-dealer member of the House of Representatives. The film was warmly received by reviewers for its satiric edge and was a moneymaker at the box office, albeit not in the blockbuster class of earlier Murphy films. Boomerang —a prefeminist if somewhat crass comedy which traded on Murphy's image as a womanizer who, in the film, sees the error of his ways when he runs up against maneater Robin Givens—inspired neither good reviews nor good box office. A third installment in the popular Beverly Hills Cop series, which seemed like a sure bet, was an unexpected flop with audiences. As was Vampire in Brooklyn , a Wes Craven horror comedy in which Murphy played several roles, including the bloodsucker of the title. But Murphy bounced back big time with his remake of the old Jerry Lewis vehicle The Nutty Professor , a comic spin on the Robert Louis Stevenson tale Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in which Lewis had played dual roles—that of a goofy, childlike professor and his chemically-induced alter ego: smooth talking lounge lizard and sleazeball Buddy Love. A huge critical and audience success for Lewis (it is considered his best film), the remake was just the shot in the arm Murphy needed to regain his crown as the king of comedy. Not to be outdone by Lewis, Murphy not only plays Buddy Love and the socially backward scientist Sherman Klump but Klump's entire family—who, at one point in the film, appear together (hilariously) in the same scene with the use of clever special effects.

In Life , a comedy-drama about two convicts who grow old together in prison, Murphy plays just one part (Martin Lawrence plays the other), but the part tests his skills (and range) not only as a comedian but as an actor for he is required to age convincingly throughout the film—a trick he brings off adroitly in what many critics consider to be his best screen performance to date.

Murphy was back to playing dual roles again in Bowfinger , a satire about low budget filmmakers on Hollywood's periphery hoping to catch the brass ring. In it, Murphy plays a black superstar of action films named Kit Ramsey, and Kit's endearingly unsuccessful brother Jiff—whose resemblance to Kit exploitation producer-director Steve Martin trades on to get his latest poverty row extravaganza off the ground. The film, which Martin scripted, is surprisingly bereft of comic high points. Laughs are infrequent—except when Murphy is on the screen; he steals the movie with his hilarious performances in both parts.

—Susan M. Doll, updated by John McCarty

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: