Barbra Streisand - Actors and Actresses

Nationality: American. Born: Barbara Joan Streisand in Brooklyn, New York, 24 April 1942. Education: Attended Erasmus Hall High School. Family: Married the actor Elliott Gould, 1963 (divorced 1971), son: Jason Emanuel; the actor James Brolin, 1998. Career: Singer in New York nightclub; 1961—professional stage debut in Another Evening with Harry Stoones ; 1963—Broadway debut in I Can Get It for You Wholesale ; recording star; 1964—phenomenal success in stage play Funny Girl , and later in film version, 1968; 1969—co-founder, with Paul Newman and Sidney Poitier, First Artists Productions; 1983—producer and director, as well as actress, Yentl . Awards: Best Actress Academy Award, David Di Donatello award for Foreign Actress, and Golden Globe award for Best Actress, for Funny Girl , 1968; David Di Donatello award for Foreign Actress, The Way We Were , 1973; Best Song Academy Award, and Golden Globe award for Best Song, for "Evergreen," in A Star Is Born , 1976; Golden Globe award for Best Director, Silver Ribbon (Italy) as Best New Foreign Director, Yentl , 1983; Women in Film Crystal Awards, 1984, 1992; Emmy Award for Outstanding Variety, Music, or Comedy Special, 1985; ASCAP Award for Most Performed Song from a Motion Picture, for "I Finally Found Someone," 1998; Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award for Lifetime Achievement, 2000. Address: 301 N. Carolwood Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90077, U.S.A.

Films as Actress:

- 1968

-

Funny Girl (Wyler) (as Fanny Brice)

- 1969

-

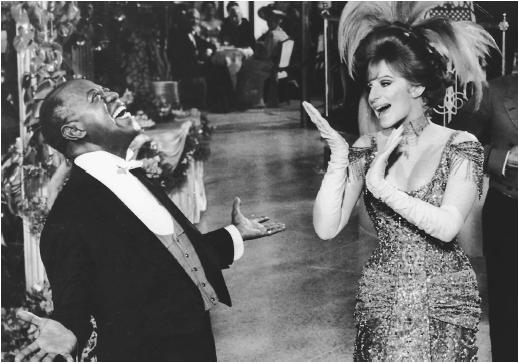

Hello Dolly! (Kelly) (as Dolly Levi)

- 1970

-

On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (Minnelli) (as Daisy Gamble); The Owl and the Pussycat (Ross) (as Doris)

- 1972

-

What's Up, Doc? (Bogdanovich) (as Judy Maxwell); Up the Sandbox (Kershner) (as Margaret Reynolds)

- 1973

-

The Way We Were (Pollack) (as Katie Morosky)

- 1974

-

For Pete's Sake (Yates) (as Henrietta)

- 1975

-

Funny Lady (Ross) (as Fanny Brice)

- 1976

-

A Star Is Born (Pierson) (as Esther Hoffman) (+ exec pr, musical concepts)

- 1979

-

The Main Event (Zieff) (as Hillary Kramer) (+ pr)

- 1981

-

All Night Long (Tramont) (as Cheryl Gibbons)

- 1983

-

Yentl (title role) (+ d, co-pr, sc)

- 1987

-

Nuts (Ritt) (as Claudia Draper) (+ pr, mus)

- 1990

-

Listen Up!: The Lives of Quincy Jones (doc)

- 1991

-

The Prince of Tides (as Susan Lowenstein) (+ d, co-pr)

- 1995

-

Barbra Streisand: The Concert (as herself—for TV) (+ pr)

- 1996

-

The Mirror Has Two Faces (as Rose Morgan) (+ d, co-pr, mus)

Other Films:

- 1995

-

Serving in Silence: The Margarethe Cammermeyer Story (Bleckner—for TV) (co-exec pr)

- 1997

-

Rescuers: Stories of Courage: Two Women (Bogdanovich) (pr)

- 1998

-

City of Peace (Koch) (exec pr); The Long Island Incident (Sargent—for TV) (exec pr)

- 1999

-

The King and I (song composer)

Publications

By STREISAND: articles—

"Symbiosis Continued," with William Wyler, in Action (Los Ange-les), March-April 1968.

"A Star Is Reborn," interview with Michael Shnayerson, in Vanity Fair , November 1994.

On STREISAND: books—

Castell, David, The Films of Barbra Streisand , London, 1974.

Spada, James, with Christopher Nickens, Streisand: The Woman and the Legend , New York, 1981.

Zec, Donald, and Anthony Fowles, Barbra: A Biography of Barbra Streisand , 1981.

Considine, Shaun, Barbra Streisand: The Woman, the Myth, the Music , London, 1986.

Swenson, Karen, Barbra: The Second Decade , Secaucus, New Jer-sey, 1986.

Gerber, Françoise, Barbra Streisand , Paris, 1988.

Kimbrell, James, Barbra: An Actress Who Sings , Boston, 1989.

Carrick, Peter, Barbra Streisand: A Biography , London, 1991.

Riese, Randall, Her Name Is Barbra: An Intimate Portrait of the Real Barbra Streisand , Secaucus, New Jersey, 1993.

Waldman, Allison J., The Barbra Streisand Scrapbook , Secaucus, New Jersey, 1994.

Gibbons, Leeza, Barbra Streisand , Broomall, 1995.

Spada, James, Streisand: Her Life , New York, 1995.

Okun, Milton, Barbra Streisand; The Concert , Port Chester, 1995.

Dennen, Barry, My Life with Barbra; A Love Story , Amherst, 1997.

Edwards, Anne, Streisand; It Only Happens Once , New York, 1997.

Harvey, Diana K., Streisand; the Pictoral Biography , Philadel-phia, 1997.

Edwards, Anne, Streisand: A Biography , New York, 1998.

Swenson, Karen, Films of Barbra Streisand , Carol Publishing Group, 1998.

Kimbrell, James, Barbra: An Actress Who Sings—An Unauthorized Biography , Collingdale, 1999.

Cunningham, Ernest W., The Ultimate Barbra , Los Angeles, 1999.

Vare, Ethlie Ann, Diva: Barbra Streisand & the Making of a Superstar , Collingdale, 1999.

On STREISAND: articles—

Carnell, R., "Barbra Streisand's Animal Crackers," in Lumiere (Melbourne), November 1973.

Stewart, G., "The Woman in the Moon," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1977.

Maslin, Janet, "Barbra Streisand" in The Movie Star , edited by Elisabeth Weis, New York, 1981.

Pally, Marcia, "Kaddish for the Fading Image of Jews in Film," in Film Comment (New York), February 1984.

Current Biography 1992 , New York, 1992.

Zoglin, Richard, "The Way She Is," in Time , 16 May 1994.

Sandler, A., "Streisand Tunes Up for Her Directing Stints," in Variety (New York), 21/27 August, 1995.

Spada, J., "Becoming Barbara," in Vanity Fair , September 1995.

Radio Times (London), 18 November 1995.

"ShowEast Filmmaker of the Year Award," in Film Journal (New York), November 1996.

"The 1996 Honorees," in Boxoffice (Chicago), November 1996.

"Don't Hate Me Because I'm Beautiful," in Premiere (Boulder), December 1996.

Radio Times (London), 25 October, 1997.

* * *

Barbra Streisand has become, by sheer force of talent and the strength of her personality, one of the icons of the American cinema and popular culture. Her career has been long, unusual, and incredibly successful, despite the fact that for such a major star, she has a relatively short list of film credits. During the late seventies and eighties when men overwhelmingly dominated the American box office, Streisand was, for the most part, the only woman consistently considered bankable, that is, a performer who could make a project happen. And having directed only three films, she has become one of the most powerful directors in Hollywood as well. In short, Streisand is an industry to herself: a director, a producer, a concert performer, a recording star, and an actress who could secure virtually any part she chooses. She is one of the few performers who has won all four major American entertainment awards: the Emmy for television work, the Grammy for music recording, the Tony for the Broadway stage, and the Academy award for film work. Incredibly, she has even won several awards for composing music. Despite her achievements, criticism of Streisand has always been centered on two fronts: first, charges of egotism and self-centeredness which her defenders reject as actually representing her perfectionism; and second, her choice of projects, many of which have been rather safe vehicles that have not especially stretched her abilities as performer.

Streisand's first screen appearance was in the role she originated on Broadway, Fanny Brice in the film Funny Girl . In Funny Girl Streisand established the persona which she was to express, with only slight variation, in a series of vehicles over the next several years: an unattractive woman, generally with Jewish vocal inflections, intelligence, ego, and humor, who disarms all about her and is able to transform herself into the successful and morally superior creature who is the romantic object of a Gentile man's affections. In Funny Girl , Streisand's energy was overwhelming, indeed threatening. Her slightly crossed eyes and long, crooked nose proved no impediment to her triumphant announcement, in her first film, that "I'm the greatest star. . . ." Along with Dustin Hoffman, Streisand was one of the new generation of Hollywood stars who refused to change their names, get plastic surgery, or conform to the conventional Hollywood stereo-types of attractiveness. That Streisand became a star at all, looking as she did, is itself a sign of her enormous talent: the strong singing voice, the comic timing, the photogenic face, the considerable onscreen charisma. To say that Streisand forced the Hollywood community and American moviegoers to reevaluate their concepts of beauty would not really be an overstatement. For her first film, Hollywood awarded Streisand an Academy Award, though in a tie with Katharine Hepburn—a symbol, as it were, of Streisand's uneasy alliance with Hollywood, a community that fears and respects her, but does not, apparently, love her with the kind of fervor they reserve for her more conventional male counterparts.

Funny Girl was followed by two musicals, On a Clear Day You Can See Forever , and the highly underrated Hello, Dolly! Her performance as Dolly Levi was controversial at the time for its tongue-in-cheek synthesis of Vivien Leigh and Mae West mannerisms. The film's climax is in a restaurant filled with patrons contemplating Streisand's beauty (rather than her talent), a concept that would have been unthinkable only several years earlier. A series of comedies harkening back to the screwball era followed, including What's Up, Doc? , in which Streisand wooed the blond WASP Ryan O'Neal, For Pete's Sake , in which Streisand starred opposite the pretty Michael Sarrazin, and The Owl and the Pussycat , in which Streisand plays opposite George Segal, and gives what many feel is her most energetic and inspired comic performance. At least two films in this period indicated untapped wells of dramatic abilities: the commercially unsuccessful feminist comedy Up the Sandbox , in which Streisand quietly and naturalistically plays a mother contemplating another pregnancy, and The Way We Were . The latter, which starred Streisand opposite blonde WASP superstar Robert Redford, was an incredibly successful and romantic film. The pairing evoked the kind of chemistry generally associated with the greatest stars of the past, such as Gable and Crawford. Streisand's persona was fundamentally the same: the awkward, ugly duckling who becomes the romantic object of a handsome man's affections. When Redford and Streisand divorce at the end of the film, it is Streisand who is morally righteous. In the three decades since the release of The Way We Were , the film looks increasingly like a great Hollywood classic, valorized and remembered, its images and sounds srongly reverberating in our national consciousness, a love story that one can put alongside Casablanca as an immortal icon of American identity.

Streisand followed The Way We Were with a series of films attacked by many for being lazy, self-indulgent, or redundant: another comedy called The Main Event ; a sequel to Funny Girl , entitled Funny Lady , in which Streisand gets to reject Omar Sharif, reversing the pattern of the original; and an almost universally reviled but commercially successful remake of A Star Is Born . The latter, like Funny Girl and Funny Lady , chronicles the rise to fame of Streisand in a narrative that also chronicles the decline and moral inferiority of the handsome man with whom she becomes involved.

Yentl definitely ushered in a new era for Streisand and her career. The story of a young Jewish woman who masquerades as a man in order to study the Talmud, this quasi-musical (in an era when the film musical had been long considered as extinct as the dinosaur) was directed and produced by Streisand. Although most critics were prepared to accuse Streisand of total self-centeredness, Yentl 's genuine and ostensible quality, for the most part, disarmed them. Certainly Streisand the director is by no means self-indulgent with Streisand the star: close-ups of Streisand do not automatically reveal the actress's "good" (left) side; occasionally, the star will even be photographed out of focus so the director can emphasize something else within the frame. The film's cinematography is extraordinary. In Yentl , director Streisand reveals a fetching sensitivity, an interest in androgyny (which would foreshadow her interest in gay and lesbian issues in the nineties), and a profoundly lyrical sensuality. Unlike A Star Is Born , Yentl seems organically unified, with all facets of production working in harmony toward one artistic end. For the first time, Streisand's love interest is as Jewish as she and not morally inferior. Much sympathy (as well as screen time) is extended to the secondary female lead in the film as well—another break with the patterns of Streisand's past films.

In 1991, Streisand both directed and acted in Prince of Tides , a deviously entertaining love story-cum-melodrama in the style of the classic women's films of the forties and fifties, updated with subtlety and intelligence to deal head-on with a variety of current issues, most notably childhood sexual abuse and the socially prescribed gender roles for men and women. To the surprise of many, including Streisand, the film turned into a huge event, winning the enthusiastic approbation of an emotionally moved public and significant critical raves. Streisand garnered sensitive performances from her son, Jason Gould, who played her on-screen son, and particularly from macho Nick Nolte, whose key scene required him to break down emotionally to childlike vulnerability as he admits to having been raped as a young boy. The negative backlash to the film was, unfortunately, muddled in sexism: criticism of Streisand's having photographed herself in a glamorous way (with no criticism of director Streisand having photographed Nolte similarly), accusations against the genre of melodrama as inherently unworthy (except to the extent that its focus is on male characters), and so forth. That the film received seven Academy award nominations, but again not one for Streisand, its director and star, became a matter for such public comment that Streisand became the de facto, acclaimed director of the year.

From 1992, Streisand worked on a variety of projects: particularly her long-awaited return to live performance—her first in over twenty-five years—via a triumphantly successful concert tour. Notably, the tour was itself marked by Streisand's expanded political consciousness: notably absent were many of the "lonely-woman-as-victim" songs that had made Streisand famous. Streisand also became increasingly involved in feminist issues, AIDS research and education, and children's rights. Although always politically active and socially conscious in the past (particularly through her philanthropic Streisand Foundation), Streisand transformed herself into Hollywood's leading liberal spokesperson, notably giving a very public and controversial speech against Colorado legislation designed to prevent civil rights protection to gays and lesbians, in the process cementing a tourism boycott against the entire state. Similarly, Streisand has been vocal in her support for the beleaguered President Clinton.

After co-producing, with Glenn Close, a successful Emmy award-winning TV movie on homophobia in the military, Serving in Silence: The Margarethe Cammermeyer Story , Streisand finally abandoned her long-cherished project of directing Larry Kramer's angry exposé of government inaction during the first wave of the AIDS epidemic, The Normal Heart . This abandonment, after having kept the optioned property away from other potential producers for so many years, angered Kramer and garnered negative publicity for Streisand, which perhaps contributed to the markedly tepid reaction to her "replacement" project (on a less overtly important subject), The Mirror Has Two Faces .

Perhaps surprisingly, although a Hollywood entertainment, The Mirror Has Two Faces is amazingly ambitious, synthesizing the genres of traditional romantic comedy with the mother/daughter melodrama. Streisand's hybrid, which works as a kind of ideological re-invention, miraculously avoiding all the sexist claptrap endemic to both genres, managed to attract a large, popular audience in an era in which "feminism" had been turned into a dirty word. Streisand's exploration of romantic vs. courtly love is a testament to the political resolve of its director's obsessive work with screenwriter Richard Lagravanese. Streisand also takes the role of Rose, and the cinematography glows with an appropriate pink burnish, its art direction witty and inspired. That The Mirror Has Two Faces was under-esteemed by both Hollywood and the critical community suggests that the film's very real intellectual achievements were, like the proverbial purloined letter, not particularly noticed, if nevertheless in plain sight. A witty, deft comedy filled with compassion (based, oddly enough, on a French film by André Cayatte), The Mirror Has Two Faces offers warm performances by Streisand and her co-star Jeff Bridges, as well as generous opportunities for a supporting cast headed by Lauren Bacall.

Including references to It Happened One Night , Brief Encounter , and particularly, Now Voyager (with its tortured mother/daughter relationship, theme of female transformation, and iconography of cigarette smoking as the epitome of romantic chic), The Mirror Has Two Faces at times is rather reflexive. The truth about lasting love, contends Bridges, is that unlike lovers in the movies, "we don't hear music when we kiss." Later, when the stars kiss for the first time, romantic soundtrack music is notably absent. Amazingly for a Hollywood film, Bridges falls in love with Streisand not because of her looks or sexual allure, but because of "your mind, your humor, your passion for ideas." Streisand's eventual physical transformation—which takes place after she and Bridges have already married—turns out to be laudably irrelevant: wittily, Bridges prefers her appearance pre-transformation. "I don't care if you are pretty," offers Bridges, "I love you anyway." The final fade-out kiss on the streets of New York suggests a feminist correction of the final scene of The Way We Were . Although this kiss is accompanied by Puccini (Streisand's metaphor for how it feels to be in love), Turandot is presented as source music from an apartment above, rather than as extra-diegetic comment.

Energized by her feminism and political activism, and now the most visible role model for Hollywood women interested in social change through art or grassroots political action, Streisand has effectively shut down her career as an actress-for-hire. Whereas once one might have looked forward to Streisand in a Bergman film (who once had wanted to cast her), or in a Scorsese film, or even in a Woody Allen film, it is clear that Streisand's future projects will continue to be carefully chosen and painstakingly produced in the service of her own artistic vision. Perhaps one emotional climax to her career is the Lifetime Achievement Award given her by the Foreign Press Association (Golden Globes), whose ceremony in 2000 was marked by a Streisand testament and climaxed by her unusually intelligent and inspiring speech, which strongly emphasized the integrity of the "work" itself as the supreme value for all artists, even those working in Hollywood.

—Charles Derry

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: