Denzel Washington - Actors and Actresses

Nationality: American. Born: Mount Vernon, New York, 28 December 1954. Education: Graduated from Fordham University with degrees in drama and journalism; studied one year at the American Conservatory Theater, San Francisco. Family: Married the actress and singer Pauletta Pearson, 1982; four children. Career: Performed with the New York Shakespeare Festival and the American Place Theater; 1981—off-Broadway in A Soldier's Play and as Malcolm X in When the Chickens Come Home to Roost ; theatrical film debut in Carbon Copy ; 1982–88—as Dr. Phillip Chandler in TV series St. Elsewhere ; 1988—on Broadway in Checkmates ; has own production company Mundy Lane Entertainment. Awards: Obie Award, for A Soldier's Play , 1982; Academy Award, Best Supporting Actor, Golden Globe, for Glory , 1989; Harvard Foundation Award, 1996. Address: PMK Public Relations, 955 South Carillo Drive, Suite 200, Los Angeles, CA 90048, U.S.A. Agent: ICM, 8942 Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90211, U.S.A.

Films as Actor:

- 1977

-

Wilma (Greenspan—for TV)

- 1979

-

Flesh & Blood (Jud Taylor—for TV)

- 1981

-

Carbon Copy (Schultz) (as Roger Porter)

- 1984

-

A Soldier's Story (Jewison) (as Pfc. Melvin Peterson); License to Kill (Jud Taylor—for TV) (as Martin Sawyer)

- 1986

-

Power (Lumet) (as Arnold Billings); The George Mckenna Story (Laneuville—for TV) (title role)

- 1987

-

Cry Freedom (Attenborough) (as Stephen Biko)

- 1988

-

Reunion (short)

- 1989

-

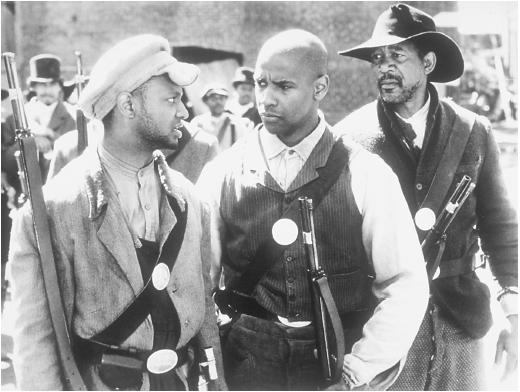

For Queen and Country (Stellman) (as Reuben James); Glory (Zwick) (as Trip); The Mighty Quinn (Schenkel) (as Xavier Quinn)

- 1990

-

Heart Condition (Parriott) (as Napoleon Stone); Mo' Better Blues (Spike Lee) (as Bleek Gilliam)

- 1991

-

Ricochet (Mulcahy) (as Nick Styles)

- 1992

-

Malcolm X (Spike Lee) (title role); Mississippi Masala (Nair) (as Demetrius)

- 1993

-

Much Ado about Nothing (Branagh) (as Don Pedro); The Pelican Brief (Pakula) (as Gray Grantham); Philadelphia (Jonathan Demme) (as Joe Miller)

- 1995

-

Virtuosity (Brett Leonard) (as Parker Barnes); Devil in a Blue Dress (Carl Franklin) (as Easy Rawlins); Crimson Tide (Tony Scott) (as Lt. Cmdr. Hunter)

- 1996

-

Courage under Fire (Zwick) (as Lt. Col. Nathaniel Serling); The Preacher's Wife (Penny Marshall) (as Dudley)

- 1998

-

Fallen (Hoblit) (as John Hobbes); He Got Game (Lee) (as Jake Shuttlesworth); The Siege (Zwick) (as Anthony "Hub" Hubbard)

- 1999

-

The Bone Collector (Noyce) (as Lincoln Rhyme); The Hurricane (Jewison) (as Rubin "Hurricane" Carter)

- 2000

-

Remembering the Titans (Yakin) (as Coach Boone)

Films as Director:

- 1999

-

Finding Fish

Publications

By WASHINGTON: articles—

Interview with Veronica Webb, and photographer Herb Ritts, in Interview (New York), July 1990.

"Denzel on Malcolm," interview with Joe Wood, in Rolling Stone (New York), 26 November 1992.

"Brothers," interview with Brendan Lemon, in Interview (New York), December 1993.

"A League of His Own," interview with Lloyd Grove, in Vanity Fair (New York), October 1995.

On WASHINGTON: books—

Nickson, Chris, Denzel Washington , New York, 1996.

Brode, Douglas, Denzel Washington: His Films and Career , Secaucus, New Jersey, 1996.

On WASHINGTON: articles—

Current Biography 1992 , New York, 1992.

Clark, John, filmography in Premiere (Boulder), November 1992.

Norment, Lynn, "Denzel Washington Opens Up about Stardom, Family and Sex Appeal," in Ebony (Chicago), October 1995.

Farley, C.J., "Pride of Place," in Time , 2 October 1995.

Rebello, S. and others, "Who's the Best Actor in Hollywood?" in Movieline (Escondido), October 1996.

* * *

Denzel Washington has insisted in interviews that he wants to be thought of as an actor , not a black actor. In one sense (which is presumably the sense he intends) this is perfectly understandable: as a star he has everything going for him, he is a gifted and intelligent actor, he has a very strong screen presence, and he is one of the handsomest men in contemporary cinema. This eminence as an actor requires no qualification. In another sense, however, in a less than ideal world still riddled with racism, it is inevitable that his blackness would be an important signifying presence in every film in which he appears.

Consider, for example, one of his less interesting films, Crimson Tide. Take away his blackness and we are left with a perfectly banal, oft-repeated plot formula: intelligent and pragmatic subordinate clashes with his older, die-hard, commanding officer, who does

Washington's presence alone illuminates these films, which give him little to do except go through the paces of a conventionally conceived and written "hero" role. The films in which Washington gives his strongest performances—which also happen to be the best in which he has appeared—all foreground in one way or another the issue of race: Malcolm X , obviously, but also Mississippi Masala , Philadelphia , and Devil in a Blue Dress. Though ultimately unsatisfying (it degenerates into contrivance and predictability), Mississippi Masala is one of the very few Hollywood films to deal in a completely frank, open, and detailed way with an interracial love relationship—though rendered "safe" for white audiences by dramatizing a relationship between an African-American and an Indian woman. Although the action is contained within only a brief time period, we watch Washington mature in the course of the film. At that time (1992) he could still look boyish, exuding an innocent charm, and the scene in the Leopard Lounge when he first dances with Mina (Sarita Choudhury) exhibits his ability to portray subtle shifts of feeling. Using Mina first merely to arouse the jealousy of an old flame who, having "made it big," has treated him with condescension, he experiences a growing attraction to her, until the old flame is forgotten. A delightful chemistry develops between Washington and Choudhury, and the crucial scene by a lake when they first kiss is played by both with marvelous delicacy. Then, when the relationship is threatened and seemingly destroyed by racial tensions, Washington visibly sheds the boyishness, seeming to age into full manhood before our eyes.

This ability not merely to delineate but to develop a character is perhaps at its most striking in Malcolm X : Washington convincingly shows us Malcolm's growth from irresponsibility to complete emotional and political maturity. If the film as a whole is somewhat disappointingly conventional—Spike Lee allows himself to slip too easily into the conventions and manner of the worthy but finally unexciting biopic—this is no fault of Washington's: he carries the film securely, and is largely responsible for its limited distinction.

Washington's two finest films are, arguably, Philadelphia and Devil in a Blue Dress. The relative commercial failure of the latter is a great disappointment: it deserved large audiences, and the studio was apparently planning to follow it with a series of adaptations of the splendid "Easy Rawlins" novels of Walter Mosley, a series which now may never materialize. The film is directed with great intelligence by Carl Franklin, and Washington's performance as an unusually fallible and vulnerable involuntary "private eye" (we are worlds removed here from Philip Marlowe) is a marvel of integrity and insight.

Tom Hanks got most of the attention (and the Best Actor Oscar) for Philadelphia —understandably, as his character, a gay man dying of AIDS, is the more showy—but Washington's performance equals his in intelligence and subtlety. Again, Washington traces with surety the character's emotional and psychological development. Initially hostile to the idea of taking on a gay client, a prey to a casual and unthinking homophobia, he comes to understand the parallels between racial prejudice and antigay prejudice, systematically casting off his homophobia intellectually (if never entirely on the emotional level). We see him, in fact, learning from the Tom Hanks character, whom he originally rejected: learning especially, in the famous "Maria Callas" scene, the value of the individual life, the essential human creativity expressed in the striving to live , not merely exist or survive.

Since the collapse of the studio system, the situation and stability of the star have been notoriously precarious. Denzel Washington is the only black star so far to achieve so great a preeminence, and to sustain it over more than a decade. One can read his recent career in terms of strategies of security, a traversal of the currently fashionable generic cycles: the "Devil" movie ( Fallen ), the "Angel" movie ( The Preacher's Wife ), the serial killer movie ( The Bone Collector ), the "Plea for Justice" movie ( The Hurricane ). Fallen is intriguing for its first half, a considerable letdown when the issues become clear. The Preacher's Wife , a remake of The Bishop's Wife with Washington in the Cary Grant role, owes most of its ideas to It's a Wonderful Life and The Bells of St. Mary's , whilst carefully avoiding the inner tensions that give those films their continuing interest; it proves mainly that frivolous romantic comedy is not his forte. The Bone Collector (out of Seven , by Silence of the Lambs ) is better than its derivative nature suggests, but mainly because of Angelina Jolie. The Hurricane gives Washington a role that displays his strengths, his intensity, his virtuosity, within the simplistic and self-righteous setting of a Norman Jewison "social protest" movie. None of these films extends him significantly.

His return to collaboration with Spike Lee gives him his one chance to shine within a film of real distinction, and he makes the most of it. He Got Game had a disappointing critical reception (everyone seems to expect Lee to remake Do the Right Thing every time he shoots a film). Its insights into the importance of sport, as one of the few areas in which American blacks have been permitted to find success, dignity, and self-respect, are cogently and movingly presented, with Washington (almost unrecognizable in beard and Afro) at his finest in an emotionally demanding role. The complex fatherson relationship is handled with great sensitivity and intelligence by director and star.

—Robin Wood

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: