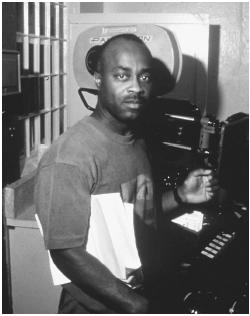

Charles Burnett - Director

Nationality: American. Born: Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1944. Education: Studied electronics at Los Angeles Community College, and theater, film, writing, arts, and languages at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Career: Directed first feature film,

Films as Director:

- 1969

-

Several Friends (short)

- 1973

-

The House (short)

- 1977

-

Killer of Sheep (+ sc, pr, ph, ed)

- 1983

-

My Brother's Wedding (+ sc, pr, ph)

- 1989

-

Guests of Hotel Astoria (+ ph)

- 1990

-

To Sleep with Anger (+ sc)

- 1994

-

The Glass Shield (+ sc)

- 1995

-

When It Rains (short)

- 1996

-

Nightjohn (for TV)

- 1998

-

The Wedding (mini for TV); Dr. Endesha Ida Mae Holland (doc/short)

- 1999

-

Selma, Lord, Selma (for TV); The Annihilation of Fish ; Olivia's Story

- 2000

-

Finding Buck McHenry

Other Films:

- 1983

-

Bless Their Little Hearts (Woodbury) (sc, ph)

- 1985

-

The Crocodile Conspiracy (ph)

- 1987

-

I Fresh (sc)

Publications

By BURNETT: articles—

"Charles Burnett," interview by S. Sharp in Black Film Review (Washington, D.C.), no. 1, 1990.

"Entretien avec Charles Burnett," interview by M. Cientat and M. Ciment in Positif (Paris), November 1990.

"They've Gotta Have Us," interview by K. G. Bates in New York Times , 14 July 1991.

Burnett, Charles, and Charles Lane, "Charles Burnett and Charles Lane," in American Film (Los Angeles), August 1991.

Burnett, Charles, "Breaking & Entering," in Filmmaker (Los Angeles), vol. 3, no. 1, 1994.

"Simple Pain," an interview with M. Arvin, in Film International (Tehran), vol. 3, no. 2, 1995.

Burnett, Charles & Lippy, Tod, "To Sleep with Anger: Writing and Directing To Sleep with Anger ," in Scenario (Rockville), Spring 1996.

On BURNETT: articles—

Reynaud, B., "Charles Burnett," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), June 1990.

Kennedy, L., "The Black Familiar," in Village Voice (New York), 16 October 1990.

Amiel, V., "To Sleep, to Dream," in Positif (Paris), November 1990.

"In from the Wilderness," in Time (New York), 17 June 1991.

Krohn, B., "Flics Story," in Cahiers du Cinéma , December 1993.

Makarah, O.F., "Director: 'The Glass Shield'," in The Independent Film & Video Monthly (New York), October 1994.

White, Armond, "Sticking to the Soul," in Film Comment (New York), January-February 1997.

Thompson, Cliff, "The Devil Beats His Wife: Small Moments and Big Statements in the Films of Charles Burnett," in Cineaste (New York), December 1997.

* * *

Prior to the release of To Sleep with Anger in 1990, Charles Burnett had for two decades been writing and directing low-budget, little-known, but critically praised films that examined life and relationships among contemporary African Americans. Killer of Sheep , his first feature, is a searing depiction of ghetto life; My Brother's Wedding knowingly examines the relationship between two siblings on vastly different life tracks; Bless Their Little Hearts (directed by Billy Woodbury, but scripted and photographed by Burnett) is a poignant portrait of a black family. But how many had even heard of these films, let alone seen them? Thanks to the emergence in the 1980s of the prolific Spike Lee as a potent box office (as well as critical) force, however, a generation of African-American moviemakers have had their films not only produced but more widely distributed.

Such was the case with To Sleep with Anger , released theatrically by the Samuel Goldwyn Company. The film, like Burnett's earlier work, is an evocative, character-driven drama about relationships between family members and the fabric of domestic life among contemporary African Americans. It is the story of Harry Mention (Danny Glover), a meddlesome trickster who arrives in Los Angeles at the doorstep of his old friend Gideon (Paul Butler). The film details the manner in which Harry abuses the hospitality of Gideon, and his effect on Gideon's family. First there is the older generation: Gideon and his wife Suzie (Mary Alice), who cling to the traditions of their Deep South roots. Gideon has attempted to pass on his folklore, and his sense of values, to his two sons. One, Junior (Carl Lumbly), accepts this. But the other, Babe Brother (Richard Brooks), is on the economic fast track—and in conflict with his family.

While set within an African-American milieu, To Sleep with Anger transcends the ethnic identities of its characters; it also deals in a generic way with the cultural differences between parents and children, the manner in which individuals learn (or don't learn) from experience, and the need to push aside those who only know how to cause violence and strife. As such, it becomes a film that deals with universal issues.

The Glass Shield is a departure for Burnett in that his scenario is not set within an African-American universe. Instead, he places his characters in a hostile white world. The Glass Shield is a thinking person's cop film. Burnett's hero is a young black officer fresh out of the police academy, JJ Johnson (Michael Boatman), who becomes the first African American assigned to a corruption-laden, all-white sheriff's station in Los Angeles. Johnson is treated roughly by the station's commanding officer and some of the veteran cops. Superficially, it seems as if he is being dealt with in such a manner solely because he is an inexperienced rookie, in need of toughening and educating to the ways of the streets. But the racial lines clearly are drawn when one of his senior officers tells him, "You're one of us. You're not a brother." Johnson, who always has wanted to be a cop, desires only to do well and fit in. And so he stands by idly as black citizens are casually stopped and harassed by his fellow officers. Even more telling, with distressing regularity, blacks seem to have died under mysterious circumstances while in custody within the confines of the precinct.

As the film progresses, Burnett creates the feeling that a bomb is about to explode. And it does, when Johnson becomes involved in the arrest of a black man, framed on a murder charge, and readily agrees to lie in court to protect a fellow officer. Burnett's ultimate point is that in contemporary America it is impossible for a black man to cast aside his racial identity as he seeks his own personal destiny. First and foremost, he is an African American, existing within a society in which all of the power is in the hands of a white male elite. But African Americans are not the sole powerless entity in The Glass Shield. Johnson befriends his station's first female officer (Lori Petty), who must deal with sexism within the confines of her precinct house as much as on the streets. Together, this pair becomes united in a struggle against a white male-dominated system in which everyday corruption and hypocrisy are the rule.

Burnett's themes—African-American identity within the family unit and, subsequently, African-American identity within the community at large—are provocative and meaningful. It seems certain that he will never direct a film that is anything short of insightful in its content.

—Rob Edelman

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: