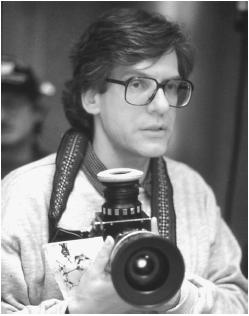

David Cronenberg - Director

Nationality:

Canadian.

Born:

Toronto, 15 March 1943.

Education:

University of Toronto, B.A., 1967.

Career:

After making two short films, made first feature,

Stereo

, 1969; travelled to France, directed filler material for Canadian TV,

1971.

Address:

David Cronenberg Productions, 217 Avenue Road, Toronto M5R 2J3, Canada.

Agent:

William Morris Agency, 151 El Camino Drive, Beverly Hills, CA 90212,

U.S.A.

Films as Director:

- 1966

-

Transfer (short) (sc, ph, ed)

- 1967

-

From the Drain (short) (sc, ph, ed)

- 1969

-

Stereo (pr, sc, ph, ed + role as Dr. Luther Stringfellow)

- 1970

-

Crimes of the Future (pr, sc, ph + role as Antoine Rouge)

- 1975

-

Shivers ( They Came from Within ; The Parasite Murders ; Frissons ) (sc)

- 1976

-

Rabid ( Rage ) (sc)

- 1978

-

Fast Company ; The Brood

- 1979

-

Scanners (sc)

- 1982

-

Videodrome (sc)

- 1983

-

The Dead Zone

- 1986

-

The Fly (co-sc, + role as gynecologist)

- 1988

-

Dead Ringers ( Twins ) (co-sc, + pr)

- 1991

-

Naked Lunch (sc)

- 1992–93

-

M. Butterfly

- 1996

-

Crash (sc + role as Auto Wreck Salesman)

- 1999

-

eXistenZ (sc)

Other Films:

- 1985

-

Into the Night (Landis) (as Group Supervisor)

- 1990

-

Nightbreed (Barker) (as Decker)

- 1992

-

Blue (McKellar) (role)

- 1994

-

Trial by Jury (Gould) (as Director); Boozecan (Campbell) (role); Henry & Verlin (Ledbetter) (as Doc Fisher)

- 1995

-

To Die For (Van Sant) (as Man at Lake); Blood and Donuts (Dale) (as Stephen)

- 1996

-

Moonshine Highway (Armstrong—for TV) (as Clem Clayton); The Stupids (Landis) (as Postal Supervisor); Extreme Measures (Apted) (as Hospital Lawyer)

- 1997

-

The Grace of God (L'Ecuyer) (role)

- 1998

-

Last Night (McKellar) (as Duncan)

- 1999

-

Resurrection (Mulcahy) (as Priest); David Cronenberg, I Have to Make the World Be Flesh (as himself)

- 2000

-

Dead by Monday (Truninger) (role)

- 2001

-

Jason X: Friday the 13th Part 10 (Isaac) (role as Dr. Wimmer)

Publications

By CRONENBERG: books—

Cronenberg on Cronenberg , with Chris Rodley, London, 1997.

Crash , New York, 1997.

Existenz: A Graphic Novel , Toronto, 1999.

By CRONENBERG: articles—

Interview in Ecran Fantastique (Paris), no. 2, 1977.

Interview in Time Out (London), 6 January 1978.

Interview in Cinema Canada (Montreal), September/October 1978.

Interview in Starburst (London), nos. 36/37, 1981.

Interview in Films (London), June 1981.

Interviews in Ecran Fantastique (Paris), June and November 1983.

Interview with S. Ayscough, in Cinema Canada (Montreal), December 1983.

Interview in Starburst (London), May 1984.

Interview with C. Tesson and T. Cazals, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), January 1987.

Interview with Brent Lewis, in Films and Filming (London), February 1987.

Interview in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1988.

Interview in American Film (Washington, D.C.), October 1988.

Interview in Cinefex (Riverside, California), November 1988.

Interview with Derek Malcolm, in the Guardian (London), 29 December 1989.

Interview in Film and Televisie , no. 419, April 1992.

Interview in Sight and Sound (London), vol. 4, no. 12, December 1994.

Interview in Sight and Sound (London), vol. 6, no. 6, June 1996.

Interview in Take One (Toronto), no. 13, Fall 1996.

Interview in Time Out (London), no. 1368, 6 November 1996.

Interview in Film Comment (New York), vol. 33, no. 2, March-April 1997.

Interview in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), vol. 78, no. 4, April 1997.

On CRONENBERG: books—

McCarty, John, Splatter Movies: Breaking the Last Taboo , New York, 1981.

Handling, Piers, editor, The Shape of Rage: The Films of David Cronenberg , Toronto, 1983.

Drew, Wayne, editor, David Cronenberg , London, 1984.

Newman, Kim, Nightmare Movies: A Critical History of the Horror Film from 1968 , London, 1988.

Morris, Peter, David Cronenberg: A Delicate Balance , Toronto, 1994.

Grant, Michael, editor, The Modern Fantastic: The Films of David Cronenberg , Westport, Connecticut, 2000.

On CRONENBERG: articles—

Film Comment (New York), March/April 1980.

"Cronenberg Section" of Cinema Canada (Montreal), March 1981.

"Cronenberg Section" of Cinefantastique (Oak Park, Illinois), Spring 1981.

Sutton, M., "Schlock! Horror! The Films of David Cronenberg," in Films and Filming (London), October 1982.

Harkness, J., "The Word, the Flesh, and the Films of David Cronenberg," in Cinema Canada (Montreal), June 1983.

Sharrett, C., "Myth and Ritual in the Post-Industrial Landscape: The Films of David Cronenberg," in Persistence of Vision (Maspeth, New York), Summer 1986.

Edelstein, R., "Lord of the Fly," in Village Voice (New York), 19 August 1986.

Lucas, Tim, in American Cinematographer (Los Angeles), September 1986.

" The Fly Issue" of Starburst (London), January 1987.

" The Fly Issue" of Ecran Fantastique (Paris), January 1987.

Newman, Kim, "King in a Small Field," in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), February 1987.

Time Out (London), 11 February 1987.

Revue du Cinéma (Paris), May 1987.

Morris, Peter, "Up from the Underground," in Take One (Toronto), no. 6, Fall 1994.

Beard, William, "Cronenberg, Flyness, and the Other-Self," in Cinémas (Montreal), vol. 4, no. 2, Winter 1994.

"Special Section," in Mensuel du Cinéma (Nice), no. 16, April 1994.

Testa, Bart, "Technology's Body: Cronenberg, Genre, and the Canadian Ethos," in Post Script (Commerce, Texas), vol. 15, no. 1, Fall 1995.

Lucas, Tim, "Ideadrome: David Cronenberg from Shivers to Dead Ringers ," in Video Watchdog (Cincinnati), no. 36, 1996.

"David Cronenberg" (special issue), in Post Script (Commerce, Texas), vol. 15, no. 2, Winter-Spring 1996.

Cowan, Noah, and Angela Baldassare, "Canadian Science Fiction Comes of Age," in Take One (Toronto), vol. 4, no. 11, Spring 1996.

Grünberg, Serge, "Crash: eros + massacre," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), no. 504, July-August 1996.

Sanjek, David, "Dr. Hobbe's Parasites: Victims, Victimization, and Gender in David Cronenberg's Shivers ," in Cinema Journal (Austin, Texas), vol. 36, no. 1, Fall 1996.

Daviau, Allen, Fred Elmes, and Stephen Pizzello, "Auto Erotic / Driver's Side," in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), vol. 78, no. 4, April 1997.

Suner, Asuman, "Postmodern Double Cross: Reading David Cronenberg's M. Butterfly as a Horror Story," in Cinema Journal (Austin, Texas), vol. 36, no. 359, Winter 1998.

* * *

David Cronenberg's breakthrough movie, Shivers , carries over the Burroughsian mind-and-body-bending themes of his underground pictures— Stereo and Crimes of the Future —but also benefits from the influence of Romero's Night of the Living Dead and Siegel's Invasion of the Body Snatchers in its horror movie imagery, relentless pacing, and general vision of a society falling apart. Thus the film locates Cronenberg at the centre of the thriving 1970s horror movement that produced such figures as Romero, Larry Cohen, John Carpenter, Wes Craven, and Tobe Hooper. While a mad scientist's creation—a horde of creeping phallic-looking parasites—infects people with a combination of venereal disease and aphrodisiac, a chilly, luxurious, modernist skyscraper apartment building becomes a Boschian nightmare of blood and carnality. An undisciplined film, Shivers gains from its scattershot approach. Cronenberg has since proved himself capable of more control but, in a movie about the encroachment of chaos upon order, it is appropriate that the narrative itself should break down. While strong enough in its mix of sex and violence to give fuel to critics who view Cronenberg as a reactionary moralist, it is clear that his approach is ambiguous, and that he is as concerned with the anomie of the normality disrupted as he is with the nature of the outbreak. The orgiastic solution of the blood parasites may be too extreme, but the soulless routine they replace suggests the straight world deserves to be eaten away from within.

His follow-up movies, Rabid , The Brood , and Scanners , develop the themes of Shivers —although his odd-man-out film, the drag-racing drama Fast Company , comes from this period also—and gradually struggle away from impersonal nihilism. Rabid is a plague story, with Marilyn Chambers quite affecting as the Typhoid Mary, while The Brood is an intense family melodrama about child abuse triggered by Nola (Samantha Eggar), a mad mother who can manifest her anger as murderous malformed children, and Scanners concerns itself with the feuds of a race of telepaths who co-exist with humanity and are unsure whether to conquer or save the world. With its exploding heads and car chases, Scanners is a progression away from the venereal apocalypse of the earlier films and is almost an upbeat movie after the icy down-ness of The Brood. Scanners has the typical early Cronenberg construction: it crams in more ideas than it can possibly deal with and tears through its overly complex plot so quickly that the holes only become apparent when it is all over. The unrelenting action of Shivers and Rabid show a society tearing itself apart; and, given the breakup of Nola's family, the incestuous cruelty of The Brood is inevitable; but Scanners follows a purposeful conflict between opposing, highly motivated sides, out of which a new world will emerge. If The Brood finds a balance between mind and body, Scanners finally achieves a hard-won harmony. Crimes of the Future, Shivers, Rabid , and The Brood all end with the persistent disease threatening to spread. In Scanners , for the first time in a David Cronenberg film, the good guys win.

Cronenberg closed this phase of his career with Videodrome , which summed up his work to date. Structurally reminiscent of Shivers , the film follows Max Renn (James Woods), a cable TV hustler whose justification for his channel's output of "softcore pornography and hardcore violence" is "better on television than in the streets." Renn is trying to track down a pirate station that is transmitting Videodrome , "a show that's just torture and murder. No plot. No characters. Very realistic," because he thinks "it's the coming thing." Underneath the stimulating images of sex and violence is a signal which causes a tumor in Renn's brain that makes him subject to hallucinations which increasingly take over the flow of the film, completely fracturing reality with disturbing developments of Cronenberg's by-now familiar bodily evolutions. A television set pulses with life and Renn buries his head in its mammary screen as he kisses the image of his fantasy lover (Deborah Harry). A vaginal slot grows from a rash on his stomach and the villains plunge living videocassettes into it which program him as an assassin. His hand and gun grow together to create a sickening biomechanical synthesis. Once Renn has been exposed to Videodrome , the film cannot hope to sustain its storyline, and, as Paul Taylor wrote in Monthly Film Bulletin , "becomes most akin to sitting before a TV screen while someone else switches channels at random."

After traveling so far into his own personal—and uncommercial—nightmare, Cronenberg felt the need to ease off by tackling an uncomplicated project. The Dead Zone , a bland but efficient adaptation of Stephen King's novel, is one of the few films he has directed without having been involved in writing the screenplay. Having proved that he could work in the mainstream, Cronenberg turned to more personal projects that still somehow pass as commercial cinema, keeping up a miraculous balancing act that has put him, in a career sense, on a much more solid footing than Romero, Hooper, Cohen, Carpenter, or Craven, all of whom he has outstripped. The Fly , a major studio remake of the 1958 monster movie, is despite its budget and lavish special effects a quintessentially Cronenbergian movie, pruning away the expected melodrama to concentrate on a single relationship, between Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum), a gawky scientist whose teleportation device has set in motion a metamorphosis that turns him into an insect, and his horrified but compassionate lover (Geena Davis). The Fly is an even more concentrated, intimate movie than The Brood , with only three main characters and one major setting. Like Rabid Rose and Max Renn, Brundle remains himself as he changes, tossing away nervous remarks about his collection of dropped-off body parts, giving an amusingly disgusting TV-chef-style demonstration of the flylike manner in which the new creature eats a doughnut, humming, "I know an old lady who swallowed a fly," and treating his mutation as a voyage of discovery.

Based on a true-life National Enquirer headline ("Twin Docs Found Dead in Posh Pad"), Dead Ringers follows the lives of Beverly and Elliot Mantle (Jeremy Irons), identical twins who develop a precocious interest in the problems of sex and the female anatomy and grow up to be a world-beating team of gynecologists. Their intense relationship, when unbalanced by the presence of a third party (Genevieve Bujold), eventually leads to their destruction. The film takes fear of surgery about as far as it can go when Beverly, increasingly infuriated that women's bodies do not conform to his textbooks, brings in a Giger-ish surrealist metalworker to create a set of "Gynecological Instruments for Operating on Mutant Women." In the theatre, Beverly is kitted up in scarlet robes more suited to a mass and horrifyingly blunders through a supposedly simple operation, wielding these bizarre and distorted implements. The home stretch is profoundly depressing, and yet deeply moving, as the twins come to resemble each other more and more in their degradation. The calculating Elliot follows Beverly into drug addiction on the theory that only if the Mantle brothers really become identical can the two inadequate personalities separate from each other and get back to some kind of functioning normality. Too often genre publications sneer at filmmakers who achieve success with horror but then claim they want to move on, but notions of genre are inherently limiting, and Cronenberg is entirely justified in leaving behind the warmed-over science-fiction elements of his earlier films and concentrating on a more intellectual, character-based mode. For the first time, he is able to present the inhuman condition without recourse (one slightly too blatant dream sequence apart, as in The Fly ) to slimy special effects, borrowings from earlier horror films, and the trappings of conventional melodrama. This is not the work of someone trying for the commecial high ground, and it certainly is not by any stretch of the imagination a mainstream movie. Dead Ringers is not a horror film. It is a David Cronenberg film, and entering the 1990s, that put it at the cutting edge of the nightmare cinema.

Cronenberg used his commercial clout to bring to the screen William S. Burroughs' novel Naked Lunch , a book that had long preoccupied him. It proved a challenge because the book is almost "unfilmable" ("It would cost hundreds of millions of dollars and be banned in every country on earth," Cronenberg has noted), so, rather than adapt the book in the traditional sense, he opted to make a film about what it was like to be William S. Burroughs. Where Dead Ringers had largely eschewed the fantastic while retaining the horrific, Naked Lunch grows from the fantastic, relegating the horrific to a minor position, in order to become a dissection of the act of creativity itself, which Cronenberg presents in the film as subversive, cathartic, and sexual act to the artist. Whereas Cronenberg had presented art as a viable outlet for release in Scanners , in Naked Lunch he seems to be saying that such a release can also lead to an inescapable trap for the artist, as well. Peter Weller's Burroughs would like to be a "normal" person, but can't. He has no choice in the matter—a viewpoint many critics interpreted as self-justification on Cronenberg's part for the nightmare images he puts on the screen.

With Naked Lunch , Cronenberg came full-circle, arriving back where he started—with an original, unsettling, dangerous, and subversive "art film" reminiscent of his earliest work. These qualities made him a seemingly natural choice to direct the film version of David Henry Hwang's bizarre, gender- and identity-bending Broadway hit M. Butterfly , about a French diplomat's (Jeremy Lyons) love affair with a Chinese opera diva whom he never realizes is a man (and spy to boot). Remarkably, the film turned out to be rather subdued and orthodox—most unCronenberg-like. He turned that around with his next film, however, the very Cronenberg-like Crash . A lover of cars in his youth (perhaps this is what the anomalous Fast Company derived from), Cronenberg had long been fascinated by J.G. Ballard's controversial science-fiction novel Crash , the story of a group of people turned on by revisiting the sites of, and even recreating, famous car wrecks such as the one that killed teen idol James Dean. The novel is disturbingly perverse, and, like Naked Lunch , "unfilmable," except that Cronenberg went ahead and filmed it anyway. As the characters keep raising the bar on their twisted hobby in order to increase their kicks and feel more alive, they start having sex with each other using their accident wounds as orifices—bizarre and horrific behavior from which Cronenberg does not avert his camera's eye. As a result, the film was slapped with the dreaded NC-17 rating until Cronenberg agreed to make some cuts to get it an "R." The NC-17 version was eventually released on video. Either version, though, is a powerful viewing experience—albeit an unwholesome and unpleasant viewing experience that makes one question, "Why am I watching this?" This is undoubtedly the kind of audience response Cronenberg was striving for (as he has throughout his career), and sought to elicit as well with his next film, eXistenZ , another twisted allegory about the sexual and others extremes people feel the need to go to keep feeling alive in today's Virtual Reality world.

—Kim Newman, updated by John McCarty

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: