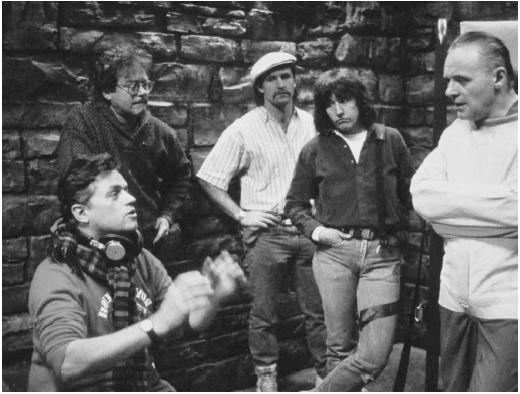

Jonathan Demme - Director

Nationality:

American.

Born:

Baldwin, New York, 1944.

Education:

University of Miami.

Military Service:

U.S. Air Force, 1966.

Family:

Married director Evelyn Purcell.

Career:

Publicity writer for United Artists, Avco Embassy, and Pathe Contemporary

Films, early 1960s; writer on

Film Daily

, 1968–69; worked in London, 1969; unit publicist, then writer for

Roger Corman, 1970; directed first film,

Caged Heat

, 1974; also director of TV films, commercials, and music videos for

recording artists Chrissie Hynde, New Order, Suzanne Vega, and others.

Awards:

Best Picture and Best Director Academy Awards, for

The Silence of the Lambs

, 1991.

Films as Director:

- 1974

-

Caged Heat (+ sc)

- 1975

-

Crazy Mama

- 1976

-

Fighting Mad (+ sc)

- 1977

-

Citizen's Band ( Handle with Care )

- 1979

-

Last Embrace

- 1980

-

Melvin and Howard

- 1983

-

Swing Shift (co-d)

- 1984

-

Stop Making Sense (doc)

- 1986

-

Something Wild (+ co-pr)

- 1987

-

Swimming to Cambodia

- 1988

-

Married to the Mob ; Famous All over Town

- 1991

-

The Silence of the Lambs ; Cousin Bobby (doc)

- 1993

-

Philadelphia (+ co-pr)

- 1994

-

The Complex Sessions

- 1997

-

Subway Stories: Tales from the Underground (exec pr)

- 1998

-

Storefront Hitchcock ; Beloved (pr)

Other Films:

- 1970

-

Sudden Terror ( Eyewitness ) (Irwin Allen) (music coordinator)

- 1972

-

Angels Hard as They Come (Viola) (pr, co-sc); The Hot Box (Viola) (pr, co-sc)

- 1973

-

Black Mama, White Mama (Romero) (co-story)

- 1985

-

Into the Night (Landis) (role)

- 1990

-

Miami Blues (pr)

- 1993

-

Household Saints (Savoca) (exec pr); Amos and Andrew (exec pr)

- 1995

-

Devil in a Blue Dress (exec pr)

- 1996

-

Mandela (pr)

- 1998

-

Shadrach (exec pr)

- 1999

-

Janis (exec pr)

- 2000

-

Maangamizi: The Ancient One (exec pr)

Publications

By DEMME: articles—

"Demme Monde," an interview with Carlos Clarens, in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1980.

Interview with Michael Stragow, in American Film (Washington, D.C.), January-February 1984.

Interview in Time Out (London), 1 July 1987.

Interview with Quentin Curtis in Independent (London), 15 June 1989.

"Identity Check," an interview with Gavin Smith in Film Comment (New York), January/February 1991.

"Jonathan Demme: Heavy Estrogen," an interview with Gary Indiana in Interview (New York), February 1991.

"Demme's monde," an interview with Amy Taubin in Village Voice (New York), 19 February 1991.

Interview with A. DeCurtis in Rolling Stone (New York), 24 March 1994.

On DEMME: book—

Winfrey, Oprah and Regan, Ken, Journey to Beloved , with Jonathan Demme, New York, 1998.

Bliss, Michael, What Goes around Comes Around: The Films of Jonathan Demme , with Christina Banks, Carbondale, 1996.

On DEMME: articles—

Goodwin, Michael, "Velvet Vampires and Hot Mamas: Why Exploitation Films Get to Us," in Village Voice (New York), 7 July 1975.

Kehr, Dave, in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1977.

Baumgarten, Marjorie, and others, " Caged Heat ," in Cinema Texas Program Notes (Austin), Spring 1978.

Maslin, Janet, in New York Times , 13 May 1979.

Black, Louis, " Crazy Mama ," in Cinema Texas Program Notes (Austin), Spring 1978.

Kaplan, James, "Jonathan Demme's Offbeat America," in New York Times Magazine , 27 March 1988.

Schruers, Fred, "Jonathan Demme: A Study in Character," in Rolling Stone (New York), 19 May 1988.

Farber, J., " Something Wild ," in Rolling Stone (New York), 2 November 1989.

DeCourcey Hinds, M., "Retelling a Psychopathic Killer's Tale Is No Joke," in New York Times , 25 March 1990.

Miller, M., "An Unlikely Director for the G-Men," in Newsweek (New York), 9 April 1990.

Vineberg, S., " Swing Shift: A Tale of Hollywood," in Sight and Sound (London), vol. 60, no. 1, 1990–1991.

Gramfors, R., article in Chaplin (Stockholm), vol. 33, no. 3, 1991.

Maslin, Janet, "How to Film a Gory Story with Restraint," in New York Times , 19 February 1991.

Ehrenstein, David, "Of Lambs and Slaughter: Director Jonathan Demme Responds to Charges of Homophobia," in Advocate , 12 March 1991.

Taubin, Amy, "Still Burning," in Village Voice (New York), 9 June 1992.

Gleick, E., "Only Lambs Are Silent," in People Weekly (New York), 22 June 1992.

Andrew, Geoff, and Floyd, Nigel, "No Hanky Panky/ The Philadelphia Story / Straight Acting," in Time Out (London), 23 February 1994.

Cunningham, M., "Breaking the Silence," in Vogue (New York), January 1994.

Green, J., "The Philadelphia Experiment," in Premiere (New York), January 1994.

Tally, Ted, "Ted Tally, on Jonathan Demme," in New Yorker , 21 March 1994.

"Jonathan Demme's Moving Pictures," in New Yorker , 31 October 1994.

Reichman, R., "I Second That Emotion," in Creative Screenwriting (Washington, D.C.), Spring 1995.

Norman, Barry, in Radio Times (London), 27 January 1996.

Cremonini, Giorgio, in Cineforum (Bergamo), March 1996.

Van Fuqua, Joy, "'Can You Feel It, Joe?': Male Melodrama and the Family Man," in Velvet Light Trap (Austin), no. 38, Fall 1996.

McCormick, Neil, "Storefront Hitchcock," in Sight and Sound (London), January 1999.

* * *

Jonathan Demme has proven himself to be one of the more acute observers of the inner life of America during the course of a directorial career that began in the early 1970s, though he began as just another protégé of the Roger Corman apprentice school of filmmaking. Demme's concern with character—focused particularly through the observation of telling eccentricities—is perhaps his trademark, combined with a vitality and willingness to use the frameworks of various genres to their fullest extent. A film such as Something Wild , for example, combines a tale of character and relationship development in an exhilarating movie which successfully mixes classic screwball comedy (you could imagine Hepburn and Tracy in the leads) with a very real menace in the closing stages that extends earlier comic confusion into the deadlier paranoia of the thriller.

Perhaps inspired by the "anything goes" aura of his Corman days, Demme has never been afraid to experiment with mood and subject matter in his films: Hitchcockian suspense in The Last Embrace , the possibilities of monologue in Swimming to Cambodia , romantic comedy in Swing Shift , horror in The Silence of the Lambs , and gangster conventions in Married to the Mob. Even his earliest films— Caged Heat and Fighting Mad (which he also wrote)—showed Demme exploiting the possibilities offered by the sex-and-violence format (rampaging girl-gangs in the first, rampaging rednecks in the second) for original and highly distinctive exploration of subjects and style.

Caged Heat also gave early signs of Demme's concern with those struggling to take control of their lives—particularly, but not exclusively, women. This examination of self-determination has remained a theme throughout his work, from the women prisoners of Caged Heat and the munitions worker (Goldie Hawn) in Swing Shift to the central characters in Something Wild (Melanie Griffith) and Married to the Mob (Michelle Pfeiffer), and contributed to his reputation as a feminist filmmaker. Their struggle to establish themselves against patriarchal attitudes epitomizes, for Demme, the struggles of the underdog, which he has called "heroic." This real concern for his characters is clear in the (usually affectionate) intensity with which they—and their lives—are portrayed, and Demme recently described his films as "a little old-fashioned, at the same time as we try to make them modern."

Demme is concerned with entertaining a mass audience, and it is probably unwise to consider the low-key mood of the earlier critically-adored films Citizen's Band (a black comedy that explores lack of communication through a small town's obsession with CB-radio) and Melvin and Howard (an offbeat comedy based on a true story of a working-class man who gave a lift to a hobo Howard Hughes in the Nevada desert) as being necessarily closest to his own heart. Both films, however good they may be, were also conscious reactions to the over-the-top nature of earlier Corman-inspired work.

Misjudgment of Demme's concerns is nothing new for the filmmaker. His much-noted focus on the everyday kitsch of Americana, for example, is driven more by an understanding of its importance as a yardstick by which America consumer society measures itself ("it's our kind of fetishism") than with being a desire to be "hip." For Demme, observing kitsch is simply a form of realism in a country where the bizarre is often real.

Though much concerned with achieving an honest view of character, Demme is not uncaring about stylish direction. A sequence such as the series of out-takes used for the final credits of Married to the Mob is one mark of a freewheeling approach to filmmaking that has roots in the knowing wit of the French New Wave (Demme cites Truffaut as an early influence), while his pared-down vision of a Talking Heads concert in Stop Making Sense is a distinctive, classy example of the rock film which pointedly eschews the tacky visual trappings too often associated with the genre.

Ultimately, though, his concern is with character rather than style—content over form. Demme is concerned more with exploring humanity than with proving himself an auteur for film critics. His own description of Married to the Mob offers an excellent insight into what he has sought in his work. "It was intelligent fun, it didn't patronise the characters or the audience, it was good-hearted. Those are tough commodities to come by." Since his late 1980s work, Demme has gone on to make two of the higher-profile films of the 1990s. The Silence of the Lambs , based on the Thomas Harris bestseller, was a film about a young FBI trainee (Jodie Foster) who locks horns with Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins), a psychopathic, cannibalistic murderer. The film, which featured fine performances and excellent direction, earned Oscars for Best Picture, Director, Actor, Actress and Adapted Screenplay—quite a haul for what is essentially a big-budget splatter film. In quite a change of pace, Demme next directed Philadelphia , a film that stars Tom Hanks as Andrew Beckett, an AIDS-afflicted lawyer who fights the system after being fired from a prestigious Philadelphia law firm. Upon the film's release, gay activists complained—sometimes bitterly—that the film soft-pedals its subject. However, Philadelphia was not produced for those who already are highly politicized and need no introduction to the reality of AIDS. The film was made for the masses who do not live in urban gay enclaves, and who have never met—or think they have never met—a homosexual, let alone a person with AIDS. As a drama, Philadelphia is not without flaws. The members of Beckett's family are unfailingly supportive and understanding, a much-too-simplistic ideal in a world in which many gays and lesbians are shunned by their relatives. It also is difficult to accept the subtle changes that occur within Joe Miller (Denzel Washington), the homophobic lawyer who takes Beckett's case. But Philadelphia does succeed in showing that homosexuals are human beings, people who deserve to be treated fairly and civilly. It enjoyed a mainstream success with audiences who normally might be turned off by a more radical, politically loaded (let alone sexually frank) film about gays or AIDS.

—Norman Miller, updated by Rob Edelman

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: