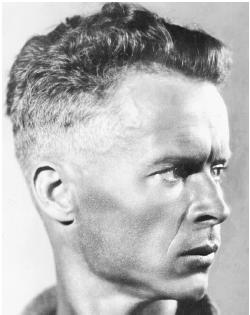

Alexander Dovzhenko - Director

Nationality: Ukrainian. Born: Sosnytsia, Chernigov province of Ukraine, 12 September 1894. Education: Hlukhiv Teachers' Institute, 1911–14; Kiev University, 1917–18; Academy of Fine Arts, Kiev, 1919. Military Service: 1919–20. Family: Married 1) Barbara Krylova, 1920 (divorced 1926); 2) Julia Solntseva, 1927. Career: Teacher, 1914–19; chargé d'affaires, Ukrainian embassy, Warsaw, 1921; attached to Ukrainian embassy, Berlin; studied painting with Erich Heckel, 1922; returned to Kiev, expelled from Communist Party, became cartoonist, 1923; co-founder, VAPLITE (Free Academy of Proletarian Literature), 1925; joined Odessa Film Studios, directed first film, Vasya-reformator , 1926; moved to Kiev Film Studios, 1928; Solntseva began as his assistant, 1929; lectured at State Cinema Institute (VGIK), Moscow, 1932; assigned to Mosfilm by

Films as Director:

- 1926

-

Vasya-reformator ( Vasya the Reformer ) (co-d, sc); Yahidka kokhannya ( Love's Berry ; Yagodko lyubvi ) (+ sc)

- 1927

-

Teka dypkuryera ( The Diplomatic Pouch ; Sumka dipkuryera ) (+ revised sc, role)

- 1928

-

Zvenyhora ( Zvenigora ) (+ revised sc)

- 1929

-

Arsenal (+ sc)

- 1930

-

Zemlya ( Earth ) (+ sc)

- 1932

-

Ivan (+ sc)

- 1935

-

Aerograd ( Air City ; Frontier ) (+ sc)

- 1939

-

Shchors (co-d, co-sc)

- 1940

-

Osvobozhdenie ( Liberation ) (co-d, ed, sc)

- 1945

-

Pobeda na pravoberezhnoi Ukraine i izgnanie Nemetskikh zakhvatchikov za predeli Ukrainskikh Sovetskikh zemel ( Victory in Right-Bank Ukraine and the Expulsion of the Germans from the Boundaries of the Ukrainian Soviet Earth ) (co-d, commentary)

- 1948

-

Michurin (co-d, pr, sc)

Other Films:

- 1940

-

Bukovyna-Zemlya Ukrayinska ( Bucovina-Ukrainian Land ) (Solntseva) (artistic spvr)

- 1941

-

Bohdan Khmelnytsky (Savchenko) (artistic spvr)

- 1942

-

Alexander Parkhomenko (Lukov) (artistic spvr)

- 1943

-

Bytva za nashu Radyansku Ukrayinu ( The Battle for Our Soviet Ukraine ) (Solntseva and Avdiyenko) (artistic spvr, narration)

- 1946

-

Strana rodnaya ( Native Land ; Our Country ) (co-ed uncredited, narration)

(films directed by Julia Solntseva, prepared or written by Dovzhenko or based on his writings):

- 1958

-

Poema o more ( Poem of an Inland Sea )

- 1961

-

Povest plamennykh let ( Story of the Turbulent Years ; The Flaming Years ; Chronicle of Flaming Years )

- 1965

-

Zacharovannaya Desna ( The Enchanted Desna )

- 1968

-

Nezabivaemoe ( The Unforgettable ; Ukraine in Flames )

- 1969

-

Zolotye vorota ( The Golden Gates )

Publications

By DOVZHENKO: books—

Izbrannoie , Moscow, 1957.

Tvori v triokh tomakh , Kiev, 1960.

Sobranie sotchinenyi (4 toma), izdatelstvo , Moscow, 1969.

Polum'iane zhyttia: spogadi pro Oleksandr a Dovzhenka , compiled by J. Solntseva, Kiev, 1973.

By DOVZHENKO: articles—

Interview with Georges Sadoul, in Lettres Françaises (Paris), 1956.

"Avtobiographia," in Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), no. 5, 1958.

"Iz zapisnykh knijek," in Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 1963.

Dovzhenko, Alexander, "Pis'ma raznyh let," in Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), April 1984.

"Listy Aleksandra Dowzenki do zony," (Letters to Julia Solntseva 1942–52), in Kino (Warsaw), May 1985.

On DOVZHENKO: books—

Yourenev, R., Alexander Dovzhenko , Moscow, 1958.

Schnitzer, Luda, Dovjenko , Paris, 1966.

Mariamov, Alexandr, Dovjenko , Moscow, 1968.

Oms, Marcel, Alexandre Dovjenko , Lyons, 1968.

Amengual, Barthélemy, Alexandre Dovjenko , Paris, 1970.

Carynnyk, Marco, editor, Alexander Dovzhenko: The Poet as Filmmaker , Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1973.

Marshall, Herbert, Masters of the Soviet Cinema: Crippled Creative Biographies , London, 1983.

Kepley, Vance, In the Service of the State: The Cinema of Alexander Dovzhenko , Madison, Wisconsin, 1986.

Nebesio, Bohdan Y., Alexander Dovzhenko: A Guide to Published Sources , Edmonton, 1995

On DOVZHENKO: articles—

"Dovzhenko at Sixty," in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1955.

Obituary in New York Times , 27 November 1956.

Montagu, Ivor, "Dovzhenko—Poet of Life Eternal," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1957.

"Dovzhenko Issue" of Film (Venice), August 1957.

Shibuk, Charles, "The Films of Alexander Dovzhenko," in New York Film Bulletin , nos. 11–14, 1961.

Robinson, David, "Dovzhenko," in The Silent Picture (London), Autumn 1970.

Carynnyk, Marco, "The Dovzhenko Papers," in Film Comment (New York), Fall 1971.

"Dovzhenko Issue" of Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), September 1974.

Biofilmography in Film Dope (London), January 1978.

Trimbach, S., "Tvorchestvo A.P. Dovzhenko i narodnaia kul'tura," in Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), no. 10, 1979.

Kepley, Vance, Jr., "Strike Him in the Eye: Aerograd and the Stalinist Terror," in Post Script (Jacksonville, Florida), Winter 1983.

Bondarchuk, Sergei, "Alexander Dovzhenko," in Soviet Film (Moscow), January 1984.

"Dovzhenko Sections," of Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), September and October 1984.

Bernard, J., "Odzak dia a mysleni Alexandra Petrovice Dovzenka," in Film a Doba (Prague), September and October 1984.

Pisarevsky, D., "Radiant Talent," in Soviet Film (Moscow), September 1984.

Navailh, F., "Dovjenko: 'L'or pur et la verite'," in Cinema (Paris), January 1985.

Amiel, Vincent, "Hommage a Dovjenko," in Positif (Paris), September 1986.

Véronneau, P., "Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1889–1968," in Revue de la Cinémathèque (Montreal), no. 2, August-September 1989.

Dovzhenko, A., "Drevnik. 1945, 1953, 1954," in Isskustvo Kino (Moscow), no. 9, September 1989.

Filmcritica (Italy), vol. 41, no. 407, July 1990.

"Nikolaj Ščors?legenda I real'nost," in Isskustvo Kino (Moscow), no. 9, September 1990.

On DOVZHENKO: film—

Hyrhorovych, Yevheniya (Evgeni Grigorovich), Alexander Dovzhenko , 1964.

* * *

Unlike many other Soviet filmmakers, whose works are boldly and aggressively didactic, Alexander Dovzhenko's cinematic output is personal and fervently private. His films are clearly political, yet at the same time he was the first Russian director whose art is so emotional, so vividly his own. His best films, Arsenal, Earth , and Ivan , are all no less than poetry on celluloid. Their emotional and poetic expression, almost melancholy simplicity, and celebration of life ultimately obliterate any external event in their scenarios. His images—most specifically, farmers, animals, and crops drenched in sunlight—are penetratingly, delicately real. With Eisenstein and Pudovkin, Dovzhenko is one of the great inventors and masters of the Russian cinema.

As evidenced by his very early credits, Dovzhenko might have become a journeyman director and scenarist, an adequate technician at best: Vasya the Reformer , his first script, is a forgettable comedy about an overly curious boy; The Diplomatic Pouch is a silly tale of secret agents and murder. But in Zvenigora , his fourth film, he includes scenes of life in rural Russia for the first time. This complex and confusing film proved to be the forerunner of Arsenal, Earth , and Ivan , a trio of classics released within four years of each other, all of which honor the lives and struggles of peasants.

In Arsenal , set in the Ukraine in a period between the final year of World War I and the repression of a workers' rebellion in Kiev, Dovzhenko does not bombard the viewer with harsh, unrealistically visionary images. Despite the subject matter, the film is as lyrical as it is piercing and pointed; the filmmaker manages to transcend the time and place of his story. While he was not the first Soviet director to unite pieces of film with unrelated content to communicate a feeling, his Arsenal is the first feature in which the totality of its content rises to the height of pure poetry. In fact, according to John Howard Lawson, "no film artist has ever surpassed Dovzhenko in establishing an intimate human connection between images that have no plot relationship."

The storyline of Earth , Dovzhenko's next—and greatest—film, is deceptively simple: a peasant leader is killed by a landowner after the farmers in a small Ukrainian village band together and obtain a tractor. But these events serve as the framework for what is a tremendously moving panorama of rustic life and the almost tranquil admission of life's greatest inevitability: death. Without doubt, Earth is one of the cinema's few authentic masterpieces.

Finally, Ivan is an abundantly eloquent examination of man's connection to nature. Also set in the Ukraine, the film chronicles the story of an illiterate peasant boy whose political consciousness is raised during the building of the Dnieper River dam. This is Dovzhenko's initial sound film: he effectively utilizes his soundtrack to help convey a fascinating combination of contrasting states of mind.

None of Dovzhenko's subsequent films approach the greatness of Arsenal, Earth , and Ivan. Stalin suggested that he direct Shchors , which he shot with his wife, Julia Solntseva. Filmed over a three-year period under the ever-watchful eye of Stalin and his deputies, the scenario details the revolutionary activity of a Ukrainian intellectual, Nikolai Shchors. The result, while unmistakably a Dovzhenko film, still suffers from rhetorical excess when compared to his earlier work.

Eventually, Dovzhenko headed the film studio at Kiev, wrote stories, and made documentaries. His final credit, Michurin , about the life of a famed horticulturist, was based on a play he wrote during World War II. After Muchurin , the filmmaker spent several years putting together a trilogy set in the Ukraine, chronicling the development of a village from 1930 on. He was sent to commence shooting when he died, and Solntseva completed the projects.

It is unfortunate that Dovzhenko never got to direct these last features. He was back on familiar ground: perhaps he might have been able to recapture the beauty and poetry of his earlier work. Still, Arsenal, Ivan , and especially Earth are more than ample accomplishments for any filmmaker's lifetime.

—Rob Edelman

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: