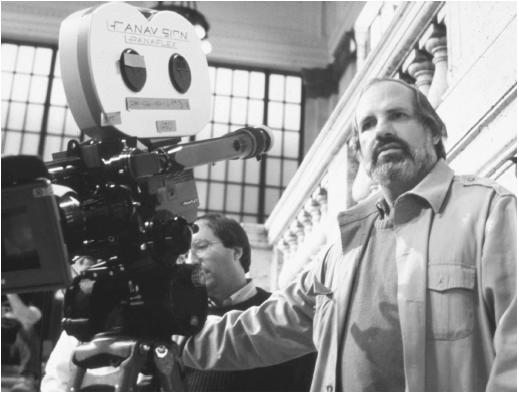

Brian De Palma - Director

Nationality:

American.

Born:

Newark, New Jersey, 11 September 1940.

Education:

Attended Columbia University, New York, and Sarah Lawrence College

(writing fellowship), 1963–64.

Family:

Married 1) actress Nancy Allen, 1979 (divorced, 1984); 2) producer Gale

Anne Hurd (divorced); 3) Darnell De Palma, 1995 (divorced, 1997); one

child.

Career:

Directed first feature,

Murder a la Mod

, 1967; also film teacher and instructor.

Awards:

Rosenthal Foundation award for

Woton's Wake

, 1963; Silver Bear Award, Berlin Festival, for

Greetings

, 1969.

Films as Director:

- 1961

-

Icarus (short); 660214, the Story of an IBM Card (short)

- 1963

-

Woton's Wake (short)

- 1964

-

Jennifer (short)

- 1965

-

Bridge That Gap (short)

- 1966

-

Show Me a Strong Town and I'll Show You a Strong Bank (short); The Responsive Eye (doc)

- 1967

-

Murder a la Mod (+ sc, ed)

- 1968

-

Greetings (+ co-sc, ed)

- 1969

-

The Wedding Party (+ pr, ed, co-sc; release delayed from 1966)

- 1970

-

Dionysus in '69 (co-d, co-ph, co-ed; completed 1968); Hi, Mom! (+ co-sc)

- 1972

-

Get to Know Your Rabbit

- 1973

-

Sisters ( Blood Sisters ) (+ co-sc)

- 1974

-

Phantom of the Paradise (+ sc)

- 1976

-

Obsession (+ co-sc); Carrie

- 1978

-

The Fury

- 1979

-

Home Movies

- 1980

-

Dressed to Kill (+ sc)

- 1981

-

Blow Out (+ sc)

- 1983

-

Scarface

- 1984

-

Body Double (+ pr, sc)

- 1986

-

Wise Guys

- 1987

-

The Untouchables

- 1989

-

Casualties of War

- 1990

-

The Bonfire of the Vanities (+ pr, role as Prison Guard)

- 1992

-

Raising Cain (+ sc)

- 1993

-

Carlito's Way

- 1996

-

Mission: Impossible

- 1998

-

Snake Eyes (+ co-sc, pr)

- 2000

-

Mission to Mars ; Mr. Hughes

Publications

By DE PALMA: articles—

Interview in The Film Director as Superstar , by Joseph Gelmis, Garden City, New York, 1970.

Interview with E. Margulies, in Action (Los Angeles), September/October 1974.

"Phantoms and Fantasies," an interview with A. Stuart, in Films and Filming (London), December 1976.

"Things That Go Bump in the Night," an interview with S. Swires, in Films in Review (New York), August/September 1978.

Interview with Serge Daney and Jonathan Rosenbaum, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), April 1982.

"Double Trouble," an interview with Marcia Pally, in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1984.

"Brian De Palma's Guilty Pleasures," in Film Comment (New York), May/June 1987.

"Brian De Palma," an interview with Robert Plunket, in Interview (New York), August 1992.

Interview with Isabelle Huppert, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), no. 477, March 1994.

Interview with Laurent Vachaud and Pierre Berthomieu, in Positif (Paris), no. 455, January 1999.

On DE PALMA: books—

Nepoti, Roberto, Brian De Palma , Florence, 1982.

Bliss, Michael, Brian De Palma , Metuchen, New Jersey, 1983.

Dworkin, Susan, Double De Palma: A Film Study with Brian De Palma , New York, 1984, revised edition, 1990.

Wood, Robin, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan , New York, 1986.

Bouzereau, Laurent, The De Palma Cut: The Films of America's Most Controversial Director , New York, 1988.

MacKinnon, Kenneth, Misogyny in the Movies: The De Palma Question , New York, 1990.

Salamon, Julie, The Devil's Candy: The Bonfire of the Vanities Goes to Hollywood , Boston, 1991.

On DE PALMA: articles—

Rubinstein, R., "The Making of Sisters ," in Filmmakers Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), September 1973.

Henry, M., "L'Oeil du malin (à propos de Brian de Palma)," in Positif (Paris), May 1977.

Brown, R. S., "Considering de Palma," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), July/August 1977.

Matusa, P., "Corruption and Catastrophe: De Palma's Carrie ," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Fall 1977.

Garel, A., "Brian de Palma," in Image et Son (Paris), December 1977.

Byron, Stuart, "Rules of the Game," in Village Voice (New York), 5 November 1979.

Jameson, R.T., "Style vs. 'Style'," in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1980.

Button, S., "Visceral Poetry," in Films (London), November 1982.

Eisen, K., "The Young Misogynists of American Cinema," in Cineaste (New York), vol. 8, no. 1, 1983.

Brown, G. A., "Obsession," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), December 1983.

Rafferty, T., "De Palma's American Dreams," in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1984.

Fisher, W., "Re: Writing: Film History: From Hitchcock to De Palma," in Persistence of Vision (Maspeth, New York), Summer 1984.

Denby, David, and others, "Pornography: Love or Death?" in Film Comment (New York), November/December 1984.

Braudy, Leo, "The Sacraments of Genre: Coppola, De Palma, Scorsese," in Film Quarterly (Los Angeles), Spring 1986.

Hugo, Chris, "Three Films of Brian De Palma," in Movie (London), Winter 1989.

White, Armond, "Brian De Palma, Political Filmmaker," Film Comment (New York), May/June 1991.

Muse, Eben J., "The Land of Nam: Romance and Persecution in Brian De Palma's Casualties of War ," in Literature/Film Quarterly , vol. 20, no. 3, 1992.

Spear, Bruce, "Political Morality and Historical Understanding in Casualties of War ," in Literature/Film Quarterly , vol. 20, no. 3, 1992.

Barry, Norman, in Radio Times (London), 5 November 1994.

Barry, Norman, in Radio Times (London), 10 June 1995

Ingersoll, Earl G. "The Constitution of Masculinity in Brian De Palma's Film Casualties of War ," in Journal of Men's Studies , August 1995.

Uffelen, René van, "Realisme even buiten spel. Het Topshot," in Skrien (Amsterdam), October-Noevenber 1995.

Scorsese, Martin, "Notre génération," March 1996

Hampton, Howard, "Rerun for Your Life: TV's Search and Destroy Mission," in Film Comment (New York), July-August 1996.

Vaz, Mark Cotta, "Cruising the Digital Backlot," in Cinefex (Riverside), September 1996.

Krohn, Bill, "Tornadoes, martiens et ordinateurs," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), September 1996.

Carlson, Jerry W., "Down the Streets of Time: Puerto Rico and New York City in the Films Q&A and Carlito's Way ," in Post Script (Commerce), vol. 16, no. 1, Fall 1996.

Magid, Ron, "Making Mission Impossible," in American Cinemtographer (Hollywood), December 1996.

Librach, Ronald S., "Sex, Lies, and Audiotape: Politics and Heuristics in Dressed to Kill and Blow Out ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), July 1998.

Eisenreich, Pierre, "Y a-t-il une vie après le stéréotype?" in Positif (Paris), no. 456, February 1999.

* * *

The conventional dismissal of Brian De Palma—that he is a mere "Hitchcock imitator"—though certainly unjust, provides a useful starting point, the relation being far more complex than such a description suggests. It seems more appropriate to talk of symbiosis than of imitation: if De Palma borrows Hitchcock's plot-structures, the impulse is rooted in an authentic identification with the Hitchcock thematic that results in (at De Palma's admittedly infrequent best) valid variations that have their own indisputable originality. Sisters and Dressed to Kill are modeled on Psycho; Obsession and Body Double on Vertigo; Body Double also borrows from Rear Window , as does Blow Out. The debt is of course enormous, but—at least in the cases of Sisters, Obsession , and Blow Out , De Palma's three most satisfying films to date—the power and coherence of the films testifies to the genuineness of the creativity.

Central to the work of both directors are the tensions and contradictions arising out of the way in which gender has been traditionally constructed in a male-dominated culture. According to Freud, the human infant, while biologically male or female, is not innately "masculine" or "feminine": in order to construct the socially correct man and woman of patriarchy, the little girl's masculinity and the little boy's femininity must be repressed. This repression tends to be particularly rigorous and particularly damaging in the male, where it is compounded by the pervasive association of "femininity" with castration (on both the literal and symbolic levels). The significance of De Palma's best work (and, more powerfully and consistently, that of Hitchcock before him) lies in its eloquent evidence of what happens when the repression is partially unsuccessful. The misogyny of which both directors have been accused, expressing itself in the films' often extreme outbursts of violence against women (both physical and psychological), must be read as the result of their equally extreme identification with the "feminine" and the inevitable dread that such an identification brings with it.

Sisters is concerned single-mindedly with castration: the symbolic castration of the woman within patriarchy, the answering literal castration that is the form of her revenge. The basis concept of female Siamese twins, one active and aggressive, one passive and submissive, is a brilliant inspiration, the action of the entire film arising out of the attempts by men to destroy the active aspect in order to construct the "feminine" woman who will accept her subordination. The aggressive sister Dominique (dead, but still alive as Danielle's unconscious) is paralleled by Grace Collier (Jennifer Salt), the assertive young reporter who usurps the accoutrements of "masculinity" and eventually assumes Dominique's place in the extraordinary climactic hallucination sequence in which the woman's castration is horrifyingly reasserted. Sisters , although weakened by De Palma's inability to take Grace seriously enough or give the character the substance the allegory demands, remains his closest to a completely satisfying film: the monstrousness of woman's oppression under patriarchy and its appalling consequences for both sexes have never been rendered more vividly. Blow Out rivals it in coherence and surpasses it in sensitivity: one would describe it as De Palma's masterpiece were it not for one unpardonable and unfortunately extended lapse—the entirely gratuitous sequence depicting the murder of the prostitute in the railway station, which one can account for only in terms of a fear that the film was not "spicy" enough for the box office (it failed anyway). It can stand as a fitting counterpart to Sisters , a rigorous dissection of the egoism fostered in the male by the culture's obsession with "masculinity." It is clear that Travolta's obsession with establishing the reality of his perceptions has little to do with an impersonal concern for truth and everything to do with his need to establish and assert the symbolic phallus at whatever cost—the cost involving, crucially, the manipulation and exploitation of a woman, eventually precipitating her death. Since Body Double —a tawdry ragbag of a film that might be seen as De Palma's gift to his detractors—De Palma seems to have abandoned the Hitchcock connection, and it is not yet clear that he has found a strong thematic with which to replace it. The Untouchables seems a work of empty efficiency; it is perhaps significant that one remains uncertain whether to take the patriarchal idyll of Elliott Ness's domestic life straight or as parody. Casualties of War is more interesting, though severely undermined by the casting of the two leads: one grasps the kind of contrast De Palma had in mind, but it is not successfully realized in that between Sean Penn's shameless mugging and Michael J. Fox's intractable blandness. Like most Hollywood movies on Vietnam, the film suffers from the inability to see Asians in terms other than an undifferentiated "otherness": it is symptomatic that the two Vietnamese girls, past and present, are played by the same actress. His return to the film of political protest (and specifically to the Vietnam War) brings De Palma's career to date full circle: his early work in an independent avant-garde ( Greetings, Hi, Mom! ) is too often overlooked. But nothing in Casualties of War , for all the strenuousness of its desire to disturb, achieves the genuinely disorienting force of the remarkable "Be Black, Baby" sections of Hi, Mom!. Following Casualties of War —a film to which he had a deep personal commitment, whatever its success or failure as a comment upon the Vietnam War, violence against women, or the power of traumatic memory—De Palma seemed intent upon remaking his own public image by choosing an unusual property for him, the social satire The Bonfire of the Vanities. He did put a personal stamp upon the material, most notably (and paradoxically) by paying tribute to the Orson Welles of Touch of Evil , opening the film with an extremely long and intricate tracking shot and using distorting wide-angle lenses almost constantly (though less imaginatively than Welles). Unfortunately the visual flair did nothing to compensate for some disastrous miscastings and craven attempts to soften the book's scathing cynicism, or for the unfocused script in general and De Palma's own inability to do satiric comedy without obnoxious overemphasis. Raising Cain , a return to more comfortable territory—the lurid pop-Freudian thriller, the genre through which De Palma had achieved greatest fame and critical admiration—puzzled those who claimed he was merely repeating himself. But for connoisseurs it was intentionally a delicious self-parody—or at least a virtuoso filmmaker's display of his special talents—most flagrantly in a spectacularly choreographed steadicam shot in which a psychiatrist spouting endless exposition is always on the verge of walking out of the frame, and in the delirious slow-motion climax.

Carlito's Way again harked back to earlier De Palma successes, this time to crime drama, with an emotional intensity somewhere between the hallucinatory Scarface and the more coolly impersonal The Untouchables. If the film ultimately could not rise beyond the conventional trajectory of its plot—ex-hood trying to go straight is drawn back into crime by his old buddy, despite the outreach of a saintly woman—it at least boasted a brilliant impersonation of a crooked lawyer by Sean Penn and some splendid De Palma set pieces, like the chase through Grand Central Terminal. The film reminds us that De Palma is unsurpassed among film directors in portraying furies: not the collective surges of violence rendered by a Sam Peckinpah, but the private demons unleashed within or witnessed by (the same thing on dream level) "ordinary" people as well as crime kings and raving lunatics. De Palma's cinematic flourishes have often been called "operatic," but perhaps the better analogy is with the Lisztian keyboard virtuoso, someone who can tap profound emotional depths one moment but skitters over the surface at other times; who frequently improvises upon others' themes but is always unmistakably himself, for better or worse.

—Robin Wood, updated by Joseph Milicia

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: