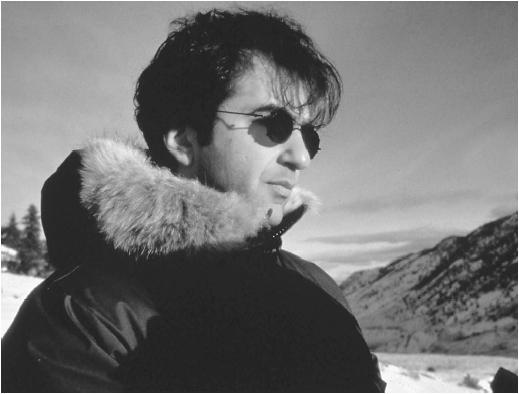

Atom Egoyan - Director

Nationality:

Canadian.

Born:

Cairo, Egypt, 19 July 1960; immigrated to Canada, 1962; naturalized

Canadian citizen.

Education:

Trinity College, University of Toronto, B.A., 1982.

Family:

Married Arsinee Khanjian (an actress); son: Arshile.

Career:

Associated with Playwrights Unit in Toronto, Ontario, Canada; director of

Ego Film Arts in Toronto, 1982—; director of episodes of television

shows such as

Alfred Hitchcock Presents

, 1985,

Twilight Zone

, 1985,

Friday the 13th

, 1987, and

Yo-Yo Ma Inspired by Bach

, 1997; director of stage productions, including

Salome

, 1996; member of jury, Cannes International Film Festival, 1996.

Awards:

Grant from University of Toronto's Hart House Film Board; prize

from Canadian National Exhibition's film festival, for Howard in

Particular; grants from Canadian Council and Ontario Arts Council; Gold

Ducat Award, Mannheim International Film Week Festival, 1984, for Next of

Kin; Toronto City Award for excellence in a Canadian production, Toronto

Film Festival, 1987, International Critics Award for Best Feature Film,

Uppsala Film Festival, 1988, and Priz Alcan from Festival du Nouveau

Cinema, 1988, all for

Family Viewing

; prize for best screenplay, Vancouver International Film Festival, 1989,

for

Speaking Parts

; Special Jury Prize, Moscow Film Festival, Golden Spike, Vallodolid Film

Festival, Toronto City Award, Toronto Film Festival, and award for best

Canadian film, Sudbury Film Festival, all 1991, all for

The Adjuster

; Golden Gate Award, San Francisco Film Festival, 1992, for

Gross Misconduct

; prize for best film in "new cinema," International Jury

for At Cinema and prize from Berlin International Film Festival, both

1994, both for Calendar; Genie awards for best picture, best director, and

best writer, International Film Critics Award, Cannes Film Festival, Prix

de la Critique for best foreign film, and Toronto City Award, Toronto

International Film Festival, all 1994, all for

Exotica.

Address:

Ego Film Arts, 80 Niagara St., Toronto, Ontario M5V 1C5, Canada.

Films as Director:

- 1979

-

Howard in Particular (+ sc, ed, ph, ro as voices)

- 1980

-

After Grad with Dad (+ sc, ed, ph, mus)

- 1981

-

Peep Show (+ sc, ed, ph)

- 1982

-

Open House (+ sc, ed)

- 1984

-

Next of Kin (+ sc, pr, ed, mus)

- 1985

-

In This Corner (TV); Men: A Passion Playground

- 1987

-

Family Viewing (+ sc, pr, ed)

- 1988

-

Looking for Nothing (TV) (+ sc)

- 1989

-

Speaking Parts (+ sc, pr)

- 1991

-

Montreal vu par. . . ( Montreal Sextet ) (segment "En passant") (+ sc); The Adjuster (+ sc, mus)

- 1993

-

Gross Misconduct (TV); Calendar (+ sc, pr, ed, ph, ro as Photographer)

- 1994

-

Exotica (+ sc, pr)

- 1995

-

A Portrait of Arshile (ro)

- 1997

-

Bach Cello Suite ν m4: Sarabande ; The Sweet Hereafter ( De beaux lendemains ) (+ sc, pr)

- 1999

-

Felicia's Journey (+ sc)

- 2000

-

Krapp's Last Tape (+ sc)

Other Films:

- 1985

-

Knock! Knock! (ro); Men: A Passion Playground (ed, ph)

- 1994

-

Camilla (as Director)

- 1995

-

Curtis's Charm (exec pr)

- 1996

-

The Stupids (as TV Studio Guard)

- 1998

-

Jack & Jill (exec pr); Babyface (exec pr)

Publications

By EGOYAN: articles—

"Ladies and Gentleman of the Jury," in Cinema Canada , no. 156, October 1988.

Interview with A. Pastor and D. Turco, in Filmcritica (Montepulciano), vol. 40, no. 396–397, June-July 1989.

Grugeau, Gérard, "Entretien avec Atom Egoyan: les élans du coeur," in 24 Images (Montréal), no. 46, November-December 1989.

Interview with E. Castiel, in Séquences (Montréal), no. 144, January 1990.

"Théorème de Pasolini," in Positif (Paris), no. 400, June 1994.

Interview with Marcus Rothe, in Jeune Cinema (Paris), no. 231, April 1995.

"Family Romance," interview with Richard Porton, in Cineaste (New York), vol. 23, no. 2, December 1997.

With Tony Rayns, in Sight and Sound (London), vol. 7, no. 10, October 1997.

Interview with S. B. Katz, in Written By (Los Angeles), vol. 2, February 1998.

On EGOYAN: articles—

24 Images , Summer 1989.

Film Comment , November-December 1989.

New Statesman and Society , 22 September 1989.

Nation , 13 July 1992.

Maclean's , 3 October 1994.

Nation , 21 March 1994.

Entertainment Weekly , 24 March 1995.

Film Comment , November-December 1995.

Film Comment , January-February 1998.

The Observer , 9 April 1995.

The Observer , 28 September 1997

Positif , special section, October 1997.

Kino (Warsaw), February 1998.

* * *

Given Atom Egoyan's background and family history, the chief preoccupations of his films might seem all but inevitable. Born in Cairo to Armenian parents, he was taken to Canada as a child and grew up in Victoria, British Columbia, a town so full of British

Add to these themes, at least in his earlier films, an uneasy fascination with the role of visual media in the modern world. Video in particular serves for Egoyan's characters as an escape route, a form of do-it-yourself therapy that allows them to evade the unsatisfactory reality around them. In Family Viewing a husband and wife lie semi-naked side by side, neither touching nor speaking, grimly watching videos of their earlier couplings that the man has taped over scenes of his son's childhood. When not viewing tapes, he calls up phone-sex lines. Two female characters in Speaking Parts , obsessed with a wannabe actor (and part-time gigolo), spend more time watching him on video than in the flesh. In The Adjuster , Egoyan's most dreamlike and elusive film, a censor secretly videotapes the porn films she's being shown—experience at third hand.

Repeatedly, Egoyan's characters try to reconstruct reality to fit their own yearnings. The protagonist of his first feature, Next of Kin , bored with his own bland WASP background, reinvents himself as the long-lost son of an expatriate Armenian family, It's typical of Egoyan's deadpan humour that the young man is accepted without question, though not looking remotely Armenian. Identity is a charade, and not even a well-acted one.

Elliptical and enigmatic, intricately structured, Egoyan's films have sometimes been called cold and contrived; though as Kent Jones notes, objecting to Egoyan's work being contrived "is a little like reprimanding Monet for his loose brushwork or dismissing Schoenberg for being atonal." As for "coldness," Egoyan resolutely shuns sentimentality, even when dealing with so emotive a subject as the death of children, but there's a soulful, troubled melancholy to his films that's counterbalanced, but never cancelled out, by a concurrent sense of the absurd. This ambiguity of tone can often be unsettling, an effect the director fully intends. He stresses that his films are "designed to make the viewer self-conscious. I revel in that . . . . The viewer has to invest themself in what they're seeing because then the emotions you are able to engage in are that much stronger."

The films often touch on disturbing territory—voyeurism, incest, paedophilia—and with their fragmented structure, give up their secrets only gradually. Sometimes, as in Exotica , a mordant study of need and exploitation set largely in a strip club, it's not until the final moments that we realise the full significance of what we've been watching—and not always even then. This mirrors the troubled outlook of his characters who rarely see anything whole, least of all themselves. Hilditch, lonely serial killer of lonely girls in Felicia's Journey , never thinks of himself as a monster. In his own eyes he's the kindest of men—just as Noah Render, the eponymous insurance man in The Adjuster , believes he's acting out of pure compassion in sexually exploiting his clients.

To date, Egoyan's most explicit statement of the cultural and emotional dislocation central to all his films comes in Calendar , where he ironically casts himself as a photographer visiting Armenia who loses his wife (played by Egoyan's own wife, actress Arsinde Khanjian) to a handsome guide. The film is at once funny and desolate, seemingly simple (by Egoyan's standards) in its structure yet teasingly oblique. Khanjian is one of a number of actors (others include David Hemblen, Elias Koteas, Bruce Greenwood and Maury Chaikin) who constantly recur in Egoyan's films, reinforcing the sense of a hermetic, inward-looking world. Venues are typically bland and drab—featureless modern hotels and offices figure frequently—without much intimation of life going on beyond the edges of the screen. Even when he portrays a community, such as the small provincial township of The Sweet Hereafter , there's little sense of social cohesion: all the houses seem remote from each other, with each person or family trapped in their own separate universe.

The Sweet Hereafter and its successor, Felicia's Journey , marked a departure in Egoyan's career, adapting material by others (novels by Russell Banks and William Trevor) instead of working to his own original scripts. Both films are sensitively crafted, keeping faith with their originals while further exploring his perennial themes of loss and disaffection. ("All my characters," he observes, "have had missing people in their lives.") In Felicia's Journey , what's more, Egoyan intriguingly maps his bleak, sardonic poetry on to the suburbs and industrial complexes of Birmingham. But the incorporation of other authorial sensibilities into his work seems to dilute the mix rather than enriching it; neither film achieves the intensity, or the complexity, of The Adjuster or Exotica. A vision as potent and idiosyncratic as that of Egoyan is perhaps best taken neat.

—Philip Kemp

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: