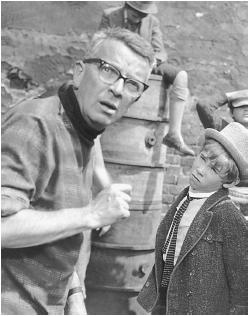

Zoltán FÁbri - Director

Nationality: Hungarian. Born: Budapest, 1917. Education: Academy of Fine Arts and Academy of Dramatic and Film Art, Budapest, diploma 1941. Career: Stage designer, actor, and director; interned as prisoner of war, 1941–45; at Artists Theatre, Budapest, 1945–49; artistic director of Hunnia Studios, 1949; made first feature, 1952; began collaboration with cameraman György Illés on Húsz óra , 1964; President of Union of Hungarian Cinema and Television Artists, and Professor at Academy of Dramatic and Cinema Arts, Budapest. Awards: Moscow Festival, for 141 perc a Befejezetlen mondatból , 1975; Grand Prize, Moscow Festival, for Az ötödik pecsét , 1977; received Kossuth Prize three times. Died: 23 August 1994, in Budapest, Hungary, of a heart attack.

Films as Director:

- 1951

-

Gyarmat a föld alatt ( Colony beneath the Earth ) (co-d)

- 1952

-

Vihar ( Storm )

- 1954

-

Eletjel ( Vierzehn Menschenleben ; Life Signs )

- 1955

-

Körhinta ( Merry-Go-Round ; Karussell ) (+ co-sc, art d)

- 1956

-

Hannibál tonár úr ( Professor Hannibal ) (+ co-sc)

- 1957

-

Bolond április ( Summer Clouds ; Crazy April ); Èdes Anna ( Anna, Schuldig? ) (+ co-sc)

- 1959

-

Dùvad ( The Brute ; Das Scheusal ) (+ sc)

- 1961

-

Két Félidö a pokolban ( The Last Goal ) (+ art d)

- 1963

-

Nappali sötétség ( Darkness in Daytime ; Dunkel bei Tageslicht ) (+ sc, art d)

- 1964

-

Húsz óra ( Twenty Hours )

- 1965

-

Vizivárosi Nyár ( A Hard Summer ) (for TV)

- 1967

-

Utószezon ( Late Season )

- 1968

-

A Pál utcai fiúk ( The Boys of Paul Street ) (+ co-sc)

- 1969

-

Isten hozta, örnagy úr! ( The Toth Family ) (+ co-sc)

- 1971

-

Hangyaboly (+ co-sc)

- 1973

-

Plusz minusz egy nap ( One Day More, One Day Less )

- 1974

-

141 perc a Befejezetlen mondatból ( 141 Minutes from the Unfinished Sentence ) (+ co-sc)

- 1976

-

Az ötödik pecsét ( The Fifth Seal ) (+ sc)

- 1977

-

Magyarok ( The Hungarians ) (+ sc)

- 1979

-

Fábián Bálint találkozása Istennel ( Balint Fabian Meets God ) (+ sc)

- 1981

-

Requiem

- 1983

-

Gyertek el a névnapomra

Publications

By FÁBRI: articles—

Interview with M. Ember, in Filmkultura (Budapest), April 1975.

"Az emberi méltóság védelme foglalkoztat," in Filmkultura (Budapest), September/October 1977.

"Bálint Fábián's Encounter with God," in Hungarofilm Bulletin (Budapest), no. 4, 1979.

Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), January 1980.

Fábri, Zoltán, "Felkertek, megirtam. Elmondanom mar nem volt szabad," in Filmkultura (Budapest), vol. 25, no. 5, 1989.

On FÁBRI: books—

Nemeskurty, Istvan, Short History of the Hungarian Cinema , New York, 1980.

Petrie, Graham, History Must Answer to Man: The Contemporary Hungarian Cinema , New York, 1981.

On FÁBRI: articles—

Biographical note, in International Film Guide , London, 1965.

Hanisch, Michael, "Zoltán Fábri," in Regiestühle , Berlin, 1972.

Biofilmography in Film und Fernsehen (Berlin), no. 3, 1976.

Nemes, K., "Egy életmü—a társadalom fejlödésében," in Filmkultura (Budapest), September/October 1977.

Revy, E., in Filmkultura (Budapest), March/April 1984.

Obituary, in Variety (New York) , 29 August 1994.

Roth, Wilhelm, "Zoltán Fábri 15.10.1917 -23.8.1994," in EPD Film (Frankfurt), October 1994.

Obituary, in Film-Dienst (Cologne), 25 October 1994.

Obituary, in Classic Images (Muscatine), October 1994.

On FÁBRI: film—

Nádassy, László, director, Fábri portré , 1980.

* * *

Having been a theatre director and designer, Zoltán Fábri began to work in films in 1950 and quickly discovered his true vocation. In 1952 he made his first film, Vihar , a drama about the collectivization of a village. Körhinta , presented at Cannes in 1956 was astonishing for the beauty of its images and feelings, and for the appearance of a young actress, Mari Töröcsik, whom he picked again two years later for his film Èdes Anna. Also in 1956 he made Hannibál tanár úr , the tragedy of a man broken by the pressure of his conformist milieu, with the outstanding Ernö Szabó in the main role. This film, honored at in the main role. This film, honored at the Karlovy Vary Festival in 1957, raised the problem of the heritage of a fascist past and indirectly attacked the oppressive atmosphere of the Stalinist period. Following the political events which supervened in 1956, it was excluded from Hungarian screens.

In all of his work, nourished by Hungarian literature, Fábri deals with moral problems bound up with the history of his country, making use of a vigorous realism. Besides the meticulous composition of his narratives, and precise evocation of atmosphere and the milieu where they unfold, it is necessary to underline the importance given to his work with actors and his own participation in the creation of some set designs.

Following a drama showing the present-day problems of life in the countryside, Dúvad , Fábri continued with Két félidö a pokolban , set in a concentration camp. The moral behavior of men in times of crisis, the confrontation of ideas and of characters, of cowardice and heroism, totally absorb him and are at the heart of all his films. In Húsz óra , made in 1964, he uses an investigation undertaken by a journalist as the starting point for a brilliant reflection on the impact in Hungary of political events in the recent past, confirming anew his abilities as an analyst and director. For this film he was again able to engage György Illés as cameraman, and they would continue a constant collaboration from that point on.

Having given the Hungarian cinema an international audience, Fábri in 1968 directed a Hungarian-American co-production, The Boys of Paul Street , faithfully adapted from the popular novel by Ferenc Molnár, a touching story of childhood heroism. After Hangyaboly , a drama that unfolds behind the walls of a convent, with Mari Töröcsik, he made 141 perc a Befejezetlen mondatból , then returned to a moral analysis of the wartime period with Az ötödik pecsét , a work of deep psychological insight that received the Grand Prize at the Moscow Festival in 1977 and remains one of the director's best films. With Magyarok and its sequel, Fábián Bálint találkozása Istennel , he traces in epic style and more conventional form the fate of the peasants in the period between the wars. In Requiem , he sets against the drama of a young girl the tragic consequences of the postwar political dislocations. In attempting thus to renew his method, he succeeds once again in powerfully expressing the message of a great moralist.

Having received the Kossuth Prize three times, as well as being president of the Union of Hungarian Cinema and Television Artists, and professor at Budapest's Academy of Dramatic and Cinema Arts, Fábri is a key figure of the Hungarian cinema.

—Karel Tabery

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: