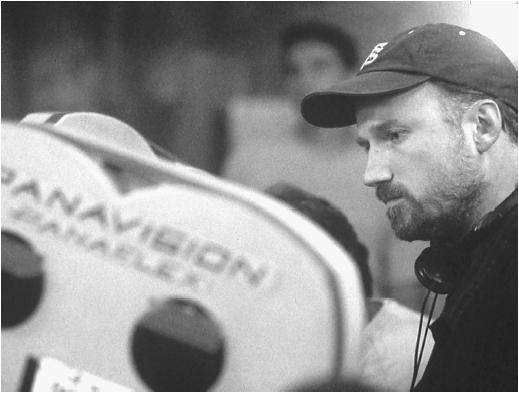

David Fincher - Director

Nationality:

American.

Born:

Colorado, 1963; raised in San Rafael, California.

Career:

Worked at an animation company as a teen; worked at Industrial Light and

Magic, c. 1981–85; director of TV commercials and music videos for

bands such as Aerosmith, Madonna, and Paula Abdul; founded Propaganda

Films production company.

Awards:

Fantosporto International Fantasy Film Award for Best Film, for

Se7en

, 1996.

Office:

Propaganda Films, 940 North Mansfield Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90038.

Agent:

Creative Artists Agency, 9830 Wilshire Blvd., Beverly Hills, CA 90212.

Films as Director:

- 1985

-

The Beat of the Live Drum

- 1992

-

Alien 3

- 1995

-

Se7en ( Seven )

- 1997

-

The Game

- 1999

-

Fight Club

Other Films:

- 1983

-

Twice upon a Time (Korty, Swenson) (special photographic effects); Star Wars: Episode VI—Return of the Jedi (Marquand) (assistant cameraman: miniature and optical effects unit)

- 1984

-

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (Spielberg) (matte photography); The NeverEnding Story ( Die Unendliche Geschichte ) (Petersen) (matte photography assistant)

- 1999

-

Being John Malkovich (Jonze) (uncredited ro as Christopher Bing)

Publications

By FINCHER: articles—

Interview in Sight and Sound (London), January 1996.

Rouyer, Philippe, " Seven, " interview in Positif (Paris), no. 420, February 1996.

Eimer, David, "Game Boy," interview in Time Out (London), no. 1416, 8 October 1997.

Probst, Christopher, "Playing for Keeps on The Game ," interview in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), vol. 78. n0. 9, September 1997.

Vachaud, Laurent, and Christian Viviani, "David Fincher: Le film d'action est sur le déclin," interview in Positif (Paris), no. 443, January 1998.

On FINCHER: articles—

Taubin, Amy, and John Wrathall, "The Allure of Decay/ Seven ," in Sight and Sound (London), vol. 6, no. 1, January 1996.

Rolling Stone , 17 October 1996.

Rolling Stone , 3 April 1997.

Entertainment Weekly , 19 September 1997.

National Review , 13 October 1997.

New York Times , 31 August 1997.

Smith, Gavin, article in Film Comment (New York), September-October 1999.

* * *

David Fincher is a devotee of darkness. Scene after scene in his films takes place in cramped, sparsely lit rooms where malignancy seems to hang in the air like ineradicable damp. For the shadows that pervade his films are moral and psychological no less than physical. Using darkness as a metaphor for evil and danger is hardly original—it is the entire basis of film noir, for a start—but Fincher brings to the banal equation a degree of emotional intensity that reinvigorates it. The darkness in his films is organic, the element in which his characters swim. When the Narrator in Fight Club quits his bland, Ikea-styled apartment to move into the derelict Victorian mansion where Tyler Durden lives, it's clear that he's coming home. This leaky ruin, squalid and underlit, is where he spiritually belongs.

On the face of it Fincher, with his dark sensibility and nervy, MTV-honed style, should have been the ideal director to take on Alien 3. It was the Alien series, after all, that had brought shadows into space, grafting the conventions of the Old-Dark-House horror movie on to a genre previously typified by brightly lit sets and gleaming, sterile surfaces. But Fincher found himself mired in a hopelessly jinxed project that had already chewed up and spat out two previous directors—not to mention a cinematographer, a small army of writers, and a lot of studio money. "I got hired for a personal vision," he later recounted, "and was railroaded into something else. I had never been devalued or lied to or treated so badly. . . . I thought I'd rather die of colon cancer than do another movie."

The experience evidently left its scars; even with three far more accomplished films to his credit, Fincher claims not to enjoy directing at all, describing it as "kind of a masochistic endeavor." Something of this penchant for willed self-torment transfers itself to his characters, haunted as they are by their demonic alter egos to the point of possession. The actions and character of John Doe (Kevin Spacey), the sadistic serial killer in Se7en , increasingly obsess Brad Pitt's young homicide detective until Doe is able to direct the cop's will, using him as an instrument to complete his own murderous design. In The Game Michael Douglas's rich banker becomes a puppet, jerked this way and that in the devious scheme devised by his scapegrace younger brother. The pattern is even there in embryo (literally) in the flawed Alien 3 , with Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) impregnated by the Alien; but it reaches its logical conclusion in Fight Club , where Edward Norton's Narrator and the dangerous, charismatic Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt again), disciple and manipulative guru, turn out to be one and the same person.

This view of people as constantly in thrall to their dark side, ever vulnerable to takeover by their worst submerged instincts, might

This kind of conceptual balancing-act requires the highest degree of precisely gauged scripting. When it's lacking, as in John Brancato and Michael Ferris's not-quite-cunning-enough screenplay for The Game , the movie lapses into ingenious spectator sport—diverting, but ultimately uninvolving. But at their most sublimely ambiguous, Fincher's films can set up disquieting tensions in the viewer—as shown by the outraged reactions of certain critics to Se7en and Fight Club. Fincher talks of being "drawn to things that begin to dismantle the architecture, not of movies, but of the pact that a movie that's responsible entertainment makes with an audience." Such disruptive tactics are never likely to make for commercial smash-hits. But if this self-styled "malcontent and miscreant" can resist pressure to tone down the edginess and mordant humour in favour of something less disturbing, his future films—and his influence on mainstream Hollywood cinema—promise to be, at the least, highly stimulating.

—Philip Kemp

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: