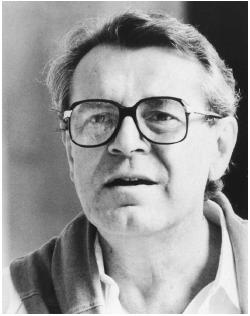

Milos Forman - Director

Nationality: Czech. Born: Kaslov, Czechoslovakia, 18 February 1932, became U.S. citizen, 1975. Education: Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, Prague, and at Film Academy (FAMU), Prague, 1951–56. Family: Married 1) Jana Brejchová, 1951 (divorced, 1956); 2) Vera Kresadlova, 1964 (divorced), two sons (twins), Matej and Petr; 3) Martina Zborilova, 28 November 1999, two sons (twins), Andrew and James (b. 1998). Career: Collaborated on screenplay for Frič's Leave It to Me , 1956; theatre director for Laterna Magika, Prague, 1958–62; directed first feature, Black Peter , 1963; moved to New York, 1969, after collapse of Dubcek government in Czechoslovakia; co-director of Columbia University Film Division, from 1975. Awards: Czechoslovak Film Critics' Prize, for Black Peter , 1963; Grand Prix Locarno, for Black Peter , 1964; Czechoslovak State Prize, 1967; Grand Prize of the Jury, Cannes Film Festival, for Taking Off , 1971 (tied with Johnny Got His Gun ); Oscar for Best Director, and Best Director Award, Directors Guild of America, and Silver Ribbon Award, Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists, for One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest , 1975; Oscar for Best Director, for Amadeus ,

1984; Golden Globe (USA) and Cesar (France) for Best Foreign Film, and

Silver Ribbon, Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists, for Best

Director, Foreign Film, for A

madeus

, 1985; Golden Globe for Best Director, for

The People vs. Larry Flynt

, 1997; Outstanding European Achievement in World Cinema, European Film

Awards, for

The People vs. Larry Flynt

, 1997 Golden Berlin Bear, Berlin International Film Festival, for

The People vs Larry Flynt

, 1997; Special Prize for Outstanding Contribution to World Cinema,

Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, 1997; Silver Berlin Bear, Berlin

International Film Festival, for

Man on the Moon

, 2000; Lifetime Achievement Award, Palm Springs International Film

Festival, 2000.

Agent:

Robert Lantz, 888 Seventh Ave., New York, NY 10106, U.S.A.

Address:

Milos Forman, The Hampshire House, 150 Central Park South, New York,

NY10019, U.S.A.

Films as Director:

- 1963

-

Cerný Petr ( Black Peter ; Peter and Pavla ); (+ co-sc); Konkurs ( Talent Competition ) (+ co-sc)

- 1965

-

Lásky jedné plavovlásky ( Loves of a Blonde ) (+ co-sc); Dobrě placená procházka ( A Well–Paid Stroll ) (+ co-sc)

- 1967

-

Hoří, má panenko ( The Firemen's Ball ) (+ co-sc)

- 1970

-

Taking Off (+ co-sc)

- 1972

-

"Decathlon" segment of Visions of Eight (+ co-sc)

- 1975

-

One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest

- 1979

-

Hair

- 1981

-

Ragtime

- 1983

-

Amadeus

- 1989

-

Valmont

- 1996

-

People vs. Larry Flynt

- 1999

-

The Little Black Book ; Man on the Moon

Other Films:

- 1955

-

Nechte to na mně ( Leave It to Me ) (Frič) (+ co-sc); Dědeček automobil ( Old Man Motorcar ) (Radok) (asst d, role)

- 1957

-

Stěnata ( The Puppies ) (+ co-sc)

- 1962

-

Tam za lesem ( Beyond the Forest ) (Blumenfeld) (asst d, role as the physician)

- 1968

-

La Pine à ongles (Carrière) (+ co-sc)

- 1975

-

Le Mâle du siècle (Berri) (story)

- 1986

-

Heartburn (Nichols) (role)

- 1989

-

New Year's Day (Jaglom) (role)

- 1990

-

Dreams of Love (pr)

- 1991

-

Why Havel? (Jasny) (narrator)

- 1992

-

L'Envers du décor: Portrait de Pierre Guffoy (Salis) (role)

- 1995

-

Heavy (Mangold) (misc. crew)

- 1996

-

Who Is Henry Jaglom? (Rubin and Workman) (role, as Himself)

- 1997

-

Cannesples 400 coups (Nadeau—for TV) (role, as Himself)

- 1998

-

V centru filmu—v temple domova (Janecek and Marek—for TV) (role, as Himself)

- 2000

-

Way Past Cool (Davidson) (pr); Keeping the Faith (Norton) (role)

Publications

By FORMAN: books—

Taking Off , with John Guare and others, New York, 1971.

Milos Forman , with others, London, 1972.

Turnaround: A Memoir , with Jan Novak, New York, 1994.

By FORMAN: articles—

"Closer to Things," in Cahiers du Cinéma in English (New York), January 1967.

Interview with Galina Kopaněvová, in Film a Doba (Prague), no. 8, 1968.

Interview, in The Film Director as Superstar , edited by Joseph Gelmis, New York, 1970.

"Getting the Great Ten Percent," an interview with Harriet Polt, in Film Comment (New York), Fall 1970.

"A Czech in New York," an interview with Gordon Gow, in Films and Filming (London), September 1971.

Interview in American Cinematographer (Los Angeles), November 1972.

Interview with L. Sturhahn, in Filmmakers Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), December 1975.

"Milos Forman: An American Film Institute Seminar on His Work," 1977.

Interview with T. McCarthy, in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1979.

Interview with Michel Ciment, in Positif (Paris), July/August 1979.

"How Amadeus Was Translated from Play to Film," an interview with M. Kakutani, in New York Times , 16 September 1984.

"The Czech Bounces Back," interview with C. Hodenfeld in Rolling Stone (New York), 27 September 1984.

Interview with Michel Ciment, in Positif (Paris), November 1984.

Interview in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), November 1984.

Forman, Milos, "Celui a qui on pense en secret," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), December 1984.

Interview in Films (London), March 1985.

Interview with T.J. Slater, in Post Script (Jacksonville, Florida), Spring/Summer and Fall 1985.

"What's Wrong with Today's Films," an interview with J. Kearney, in American Film (Washington, D.C.), May 1986.

Interview in Première (Paris), July 1987.

Interview with Michel Ciment, in Positif (Paris), December 1989.

Forman, Milos, "L'opera muet," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), May 1991 (supplement).

Interview with Nell Scovell, in Vanity Fair (New York), February 1994.

Interview with Holly Millea, "Warning: Material Is of an Adult Nature. This Literature Is Not Intended for Minors" in Premiere (New York), December 1996.

Interview with Cédric Anger and Frédéric Strauss, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), February 1997.

"Porn Again: The People vs. Larry Flynt, " an interview with Richard Porton, in Cineaste (New York), March 1997.

"Porn in the USA," an interview with David Eimer, in Time Out (London), 26 March 1997.

"Defender of the Artist and the Common Man," an interview with Kevin Lewis, in DGA Magazine (Los Angeles), March-April 1997.

Interview with Rachel Abramowitz, in Premiere (Boulder), January 2000.

Interview with Courtney Love, in Interview (New York), January 2000.

Interview with Ian Spelling, "Hello, My Name Is Andy and This Is My Feature," in Film Review (London), March 2000.

On FORMAN: books—

Boček, Jaroslav, Modern Czechoslovak Film 1945–1965 , Prague, 1965.

Skvorecký, Josef, All the Bright Young Men and Women , Toronto, 1971.

Henstell, Bruce, editor, Milos Forman, Ingrid Thulin , Washington, D.C., 1972.

Liehm, Antonín, Closely Watched Films , White Plains, New York, 1974.

Liehm, Antonín, The Milos Forman Stories , White Plains, New York, 1975.

Vecchi, Paolo, Milos Forman , Florence, 1981

Slater, Thomas, Milos Forman: A Bio-Bibliography , New York, 1987.

Liehm, Antonin, Pribehy Milos Forman , Prague, 1993.

On FORMAN: articles—

Dyer, Peter, "Star-crossed in Prague," in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1965/66.

Bor, Vladimír, "Formanovský film a nekteré předsudky" ["The Formanesque Film and Some Prejudices"], in Film a Doba (Prague), no. 1, 1967.

Effenberger, Vratislav, "Obraz človeka v českém film" ["The Portrayal of Man in the Czech Cinema"], in Film a Doba (Prague), no. 7, 1968.

"Director of the Year," International Film Guide (London and New York), 1969.

Combs, Richard, "Sentimental Journey," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1977.

Baker, B., "Milos Forman," in Film Dope (London), April 1979.

Cameron, J., "Milos Forman and Hair : Styling the Age of Aquarius," in Rolling Stone (New York), 19 April 1979.

Stein, H., "A Day in the Life: Milos Forman: Moment to Moment with the Director of Hair ," in Esquire (New York), 8 May 1979.

Holloway, Ron, "Columbia U.'s Film School Now Attracts Europe's Helmers," in Variety (New York), 14 January 1981.

Buckley, T., "The Forman Formula," in New York Times , 1 March 1981.

Kennedy, Harlan, " Ragtime : Milos Forman Searches for the Right Key," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), December 1981.

Quart, Leonard, and Barbara Quart, " Ragtime without a Melody," in Literature-Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 10, no. 2, 1982.

Kamm, M., "Milos Forman Takes His Camera and Amadeus to

Prague," in New York Times , 29 May 1983.

Jacobson, H., "Mostly Mozart: As Many Notes as Required," in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1984.

Harmetz, Aljean, "Film Makers in a Race over Les liaisons ," in New York Times , 10 February 1988.

"Four Who've Made It," in Variety (New York), 25 October 1989.

Dudar, Helen, "Milos Forman Takes a New Look at Old Loves," in New York Times , 12 November 1989.

Goodman, Walter, "Forman in His Own and Others' Words," in New York Times , 22 December 1989.

Warchol, T., "The Rebel Figure in Milos Forman's American Films," in New Orleans Review , 1990.

Wharton, Dennis, "Top Directors Get behind Film-labeling Legislation," in Variety , July 29, 1991.

Cohn, L., "A Tale of Two Expatriate Filmmakers," in Variety (New York), 29 January 1992.

Newman, Kim, review of People vs. Larry Flynt in Empire (London), May 1997.

Jensen, Jeff, "Moon Landing," in Entertainment Weekly (New York), 10 December 1999.

McCarthy, Todd, "'Moon' Trip Revelation: There's No There There," in Variety (New York), 13 December 1999.

Travers, Peter, " Man on the Moon ," in Rolling Stone (New York), 30 December 1999.

On FORMAN: film—

Weingarten, Mira, Meeting Milos Forman , U.S., 1971.

* * *

In the context of Czechoslovak cinema in the early 1960s, Milos Forman's first films ( Black Peter and Talent Competition ) amounted to a revolution. Influenced by Czech novelists who revolted against the establishment's aesthetic dogmas in the late 1950s rather than by Western cinema (though the mark of late neorealism, in particular Ermanno Olmi, is visible), Forman introduced to the cinema after 1948 (the year of the Communist coup) portrayals of working-class life untainted by the formulae of socialist realism.

Though Forman was fiercely attacked by Stalinist reviewers initially, the more liberal faction of the Communist Party, then in ascendancy, appropriated Forman's movies as expressions of the new concept of "socialist" art. Together with great box office success and an excellent reputation gained at international festivals, these circumstances transformed Forman into the undisputed star of the Czech New Wave. His style was characterized by a sensitive use of nonactors (usually coupled with professionals); refreshing, natural-sounding, semi-improvised dialogue that reflected Forman's intimate knowledge of the milieu he was capturing on the screen; and an unerring ear for the nuances of Czech folk-rock and music in general.

All these characteristic features of Forman's first two films are even more prominent in Loves of a Blonde , and especially in The Firemen's Ball. The latter film works equally well on one level as a realistic, humorous story and on an allegorical level that points to the aftermath of the Communist Party's decision to reveal some of the political crimes committed in the 1950s (the Slánský trial). In all these films—developed, except for Black Peter , from Forman's original ideas—he closely collaborated with scriptwriters Ivan Passer and Jaroslav Papousek, who later became directors in their own right.

Shortly after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, The Firemen's Ball was banned and Forman decided to remain in the West, where he was working on the script for what was to become the only film in which he would apply the principles of his aesthetic method and vision to indigenous American material, Taking Off. It is also his only American movie developed from his original idea; the rest are either adaptations or based on real events.

Traces of the pre-American Forman are easily recognizable in his most successful U.S. film, One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest , which radically changed Ken Kesey's story and—just as in the case of Papousek's novel Black Peter —brought it close to the director's own objective and comical vision. The work received an Oscar in 1975. In that year Forman became an American citizen.

The Forman touch is much less evident in his reworking of the musical Hair , and almost—though not entirely—absent from his version of E.L. Doctorow's novel Ragtime. The same is true of the box-office smash hit and multiple Oscar winner Amadeus , and his later adaptation, Valmont. Of marginal importance are the two remaining parts of Forman's oeuvre, The Well-Paid Stroll , a jazz opera adapted from the stage for Prague TV, and Decathlon , his contribution to the 1972 Olympic documentary Visions of Eight. Forman is a merciless observer of the comedie humaine and has often been accused of cynicism, both in Czechoslovakia and in the West. To such criticisms he answers with the words of Chekhov, pointing out that what is cruel in the first place is life itself. But apart from such arguments, the rich texture of acutely observed life and the sensitive portrayal of and apparent sympathy for people as victims—often ridiculous—of circumstances over which they wield no power, render such critical statements null and void. Forman's vision is deeply rooted in the anti-ideological, realistic, and humanist tradition of such "cynics" of Czech literature as Jaroslav Hasek ( The Good Soldier Svejk ), Bohumil Hrabal ( Closely Watched Trains ) or Josef Skvorecký (whose novel The Cowards Forman was prevented from filming by the invasion of 1968).

Although the influence of Forman's filmmaking methods may be felt even in some North American films, his lasting importance will, very probably, rest with his three Czech movies. Taking Off , a valiant attempt to show America to Americans through the eyes of a sensitive, if caustic, foreign observer, should be added to this list as well. After the mixed reception of this film, however, Forman turned to adaptations of best sellers and stage hits.

In the early 1990s Forman was inactive as a director, with a gap of almost seven years between Valmont and People vs. Larry Flynt. Valmont attempted to capture the spirit of his smash hit Amadeus but suffers in the comparison. Moreover, it was released after Stephen Frears' superior Dangerous Liaisons , adapted from the same Choderlos de Laclos novel. Forman remains an outstanding craftsman and a first-class actors' director; however, in the context of American cinema he does not represent the innovative force he was in Prague.

Nevertheless, in the late 1990s he has returned to something like his earlier form with the somewhat idealistic People vs. Larry Flynt , the story of a pornographer's efforts to keep his magazine on the newsstands in a fight for freedom of speech. The more melancholy Man on the Moon is a biographical film about the comedian Andy Kaufman, who died of cancer aged thirty-five, after a turbulent career that saw him first lauded and then dumped by TV networks nervous about his erratic style. Both films have re-established Forman as an arch commentator on American popular culture.

Besides filmmaking, Forman has also been involved in the academic world in recent years, accepting a position as professor of film and co-chair of the film division at Columbia University's School of the Arts. He also appeared onscreen in several small roles, such as Catherine O'Hara's husband in Mike Nichols' Heartburn , in which he was reunited with his One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest star, Jack Nicholson, and, oddly enough, as an apartment house janitor in Henry Jaglom's New Years' Day. He has appeared as himself in several documentaries.

—Josef Skvorecký, updated by Rob Edelman and Chris Routledge

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: