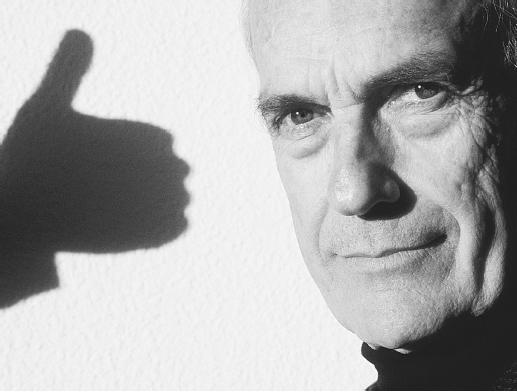

Tomás GutiÉrrez Alea - Director

Nationality: Cuban. Born: Havana, 11 December 1928. Education: Studied law at the University of Havana; attended Centro Sperimentale, Rome, 1951–53. Career: Worked with Cine-Revista newsreel organisation, late 1950s; following establishment of Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematograficos (ICAIC) by revolutionary government, began making documentaries, 1959; later collaborated with younger filmmakers, in keeping with ICAIC policy. Awards: Union of Writers of the URSS Award, Moscow International Film Festival, for Historias de la revolucion , 1961; Grand Coral—First Prize, for Tiempo de revancha , 1982; Grand Coral—First Prize, for Hasta cierto punto , 1983; Silver Berlin Bear Award and Teddy Award, Berlin International Film Festival, Golden Kikito, Gramado Latin Film Festival, ARCI-NOVA Award, FIPRESCI Award, Grand Coral—First Prize, OCIC Award, and Special Jury Award, Sundance Film Festival, for Strawberry and Chocolate , 1994; Grand Coral—Second Prize, shared with Juan Carlos Tabío, Havana Film Festival,

Films as Director:

- 1947

-

La Caperucita roja ; El Faquir

- 1950

-

Una Confusión cotidiana

- 1953

-

Il Sogno de Giovanni Bassain

- 1955

-

El Mégano

- 1959

-

Esta tierra nuestra (+ sc, ed)

- 1960

-

Asamblea general ; Historias de la revolución ( Stories of the Revolution ) (+ sc)

- 1961

-

Muerte al invasor

- 1962

-

Las Doce sillas ( The Twelve Chairs ) (+ sc)

- 1964

-

Cumbite (+ sc)

- 1966

-

La Muerte de un burócrata ( Death of a Bureaucrat ) (+ sc)

- 1968

-

Memorias del subdesarrollo ( Historias del subdesarrollo ; Inconsolable Memories ; Memories of Underdevelopment ) (+ sc, ro)

- 1971

-

Una Pelea cubana contra los demonios ( A Cuban Fight against Demons ) (+ sc)

- 1974

-

El Arte del tabaco

- 1975

-

El Camino de la mirra y el incienso

- 1976

-

La Última cena ( The Last Supper )

- 1977

-

De cierta manera ( One Way or Another ) (+ sc); La Sexta parte del mundo

- 1979

-

Los Sobrevivientes ( The Survivors ) (+ sc)

- 1984

-

Hasta cierto punto ( Up to a Certain Point ; Up to a Point )

- 1988

-

Cartas del parque ( Letters from the Park ) (+ sc)

- 1991

-

Contigo en la distancia ( Far Apart )

- 1993

-

Fresa y chocolate ( Strawberry and Chocolate )

- 1994

-

Guantanamera (+ sc)

Other Films:

- 1975

-

El Otro Francisco ( The Other Francisco )

Publications

By GUTIÉRREZ ALEA: book

Las doce sillas , Havana, 1963.

By GUTIÉRREZ ALEA: articles

"Individual Fulfillment and Collective Achievement: An Interview with Tomás Gutiérrez Alea," with Julianne Burton, in Cineaste (New York), January 1977.

"Toward a Renewal of Cuban Revolutionary Cinema," an interview with Zuzana Mirjam Pick, in Cine-Tracts (Montreal), no. 3/4, 1978.

Interview with G. Chijona, in Framework (Norwich), Spring 1979.

Interview with M. Ansara, in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), May/June 1981.

"Dramaturgia (cinematografica) y realidad," in Cine Cubano (Havana), no. 105, 1983.

Interview with E. Colina, in Cine Cubano (Havana), no. 109, 1984.

"I Wasn't Always a Filmmaker," in Cineaste (New York), vol. 14, no. 1, 1985.

Interview with Gary Crowdus, in Cineaste (New York), vol. 14, no. 2, 1985.

Interview with J. R. MacBean, in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Spring 1985.

"The Viewer's Dialectic," in Reviewing Histories: Selections from New Latin American Cinema , edited by Coco Fusco, Buffalo, New York, 1987.

"Another Cinema, Another World, Another Society," in Journal of Third World Studies , vol. 11, no. 1, 1994.

West, Dennis, " Strawberry and Chocolate , Ice Cream and Tolerance: Interviews with Tomás Gutiérrez Alea and Juan Carlos Tabío," in Cineaste (New York), vol. 21, no. 1–2, 1995.

On GUTIÉRREZ ALEA: books

Nelson, L., Cuba: The Measure of a Revolution , Minneapolis, 1972.

Myerson, Michael, editor, Memories of Underdevelopment: The Revolutionary Films of Cuba , New York, 1973.

Chanan, Michael, The Cuban Image: Cinema and Cultural Politics in Cuba Bloomington , Indiana, 1985.

Oroz, Silvia, Os filmes que Não Filmei: Gutiérrez Alea , Rio de Janeiro, 1985.

Burton, Julianne, editor, Cinema and Social Change in Latin America: Conversations with Filmmakers , Austin, Texas, 1986.

Fornet, Ambrosio, editor, Alea: Una retrospectiva critica , Havana, 1987.

Douglas, María Eulalia, Diccionario de Cineastas Cubanos: 1959–1987 , Merida, Venezuela, 1989.

Chanan, Michael, editor, Memories of Underdevelopment, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, Director, and Inconsolable Memories , London, 1990.

Paranagua, Paulo Antonio, editor, Le Cinema Cubain , Paris, 1990.

Pick, Zuzana M., The New Latin American Cinema: A Continental Project , Austin, Texas, 1993.

Tomás Gutiérrez Alea: poesí y revolución , Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 1994.

Evora, José Antonio, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea , Madrid, 1996.

On GUTIÉRREZ ALEA: articles

Sutherland, Elizabeth, "Cinema of Revolution—Ninety Miles from Home," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Winter 1961/62.

Adler, Renata, in New York Times , 10, 11, and 12 February 1969.

Engel, Andi, "Solidarity and Violence," in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1969.

Crowdus, Gary, "The Spring 1972 Cuban Film Festival Bust," in Film Society Review (New York), March/May 1972.

Lesage, Julia, "Images of Underdevelopment," in Jump Cut (Chicago), May/June 1974.

Kernan, Margot, "Cuban Cinema: Tomás Gutiérrez Alea," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Winter 1976.

Burton, Julianne, "Introduction to Revolutionary Cuban Cinema," in Jump Cut (Chicago), December 1978.

West, Dennis, "Slavery and Cinema in Cuba: The Case of Gutiérrez Alea's The Last Supper ," in Western Journal of Black Studies , Summer 1979.

Alexander, W., "Class, Film Language, and Popular Cinema," in Jump Cut (Berkeley), March 1985.

Burton, Julianne, "The Intellectual in Anguish: Modernist Form and Ideology in Land in Anguish and Memories of Underdevelopment," in Ideologies and Literature , Winter-Spring 1985.

West, Dennis, " The Last Supper ," in Magill's Survey of Cinema: Foreign Language Films , edited by Frank N. Magill, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1985.

Sanchez Crespo, Osvaldo, "The Perspective of the Present: Cuban History, Cuban Filmmaking," in Reviewing Histories: Selections from New Latin American Cinema , edited by Coco Fusco, Buffalo, New York, 1987.

West, Dennis, "Cuba: Cuban Cinema before the Revolution and After," in World Cinema since 1945 , edited by William Luhr, New York, 1987.

"Tomás Gutiérrez Alea," in Film Dope (London), March 1988.

Chanan, Michael, "Tomás Gutiérrez Alea: The Man in Havana," in National Film Theatre Booklet (London), October/November 1989.

Fornet, Ambrosio, "Alea: Diez notas en busca de un autor," in Encuadre (Venezuela), vol. 11, 1992.

Chávez, Rebeca, "Tomás Gutiérrez Alea: Entrevista filmada," in La Gaceta de Cuba , September-October 1993.

Padrón Nodarse, Frank, "La realidad en el cine cubano de los noventa," in Dicine , vol. 57, 1994.

Strawberry and Chocolate issue of Viridiana (Madrid), no. 7, 1994.

González, Reynaldo, "Meditation for a Debate, or Cuban Culture with the Taste of Strawberry and Chocolate ," in Cuba Update , May 1994.

Mason, Joyce, "State Machismo: The Official Versions of the State of Male/Female Relations," in Cineaction , May 1986.

Jaramillo, Diana, "El sabor de la cubanía," in Kinetoscopio , May-June 1994.

Yglesias, Jorge, "La espera del futuro," in Kinetoscopio , November-December 1994.

Cotler, Andrés, "Contradicciones cubanas: Fresa y chocolate ," in La Gran Ilusion , vol. 4, 1995.

Espinasa, JoséMaría, " Fresa y chocolate : Un cuento de hadas," in Nitrato de Plata , vol. 20, 1995.

Mraz, John, "Memorias del subdesarrollo: Conciencia burguesa, contexto revolucionario," in Nitrato de Plata , vol. 20, 1995.

Martínez Carril, Manuel, "Gutiérrez Alea observa a Cuba desde adentro," in Cinemateca Revista , January 1995.

Wise, Michael Z., "In Totalitarian Cuba, Ice Cream and Understanding," in New York Times , 22 January 1995.

Marsolais, Gilles, "Un humour décapant: coup d'oeil sur quelques films de Tomás Gutiérrez Alea," in 24 Images (Montreal), no. 77, Summer 1995.

Obituary in Cineaste (New York), vol. 22, no. 2, Spring 1996.

Obituary in Variety (New York), 22 April 1996.

Obituary in Cineaste (New York), June 1996.

Obituary in Sight and Sound (London), vol. 7, no. 3, March 1997.

Chanan, Michael, "Remembering Titón," in Jump Cut (Berkeley), no. 41, May 1997.

* * *

In 1946, when he was 17 years old, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea came into possession of a 16mm movie camera. As he related later in a Cinéaste essay titled "I Wasn't Always a Filmmaker," his first effort was a Kafkaesque comedy called Una confusion cotidiana ( An Everyday Confusion ). "The film was about ten minutes long, I worked with actors, and the experience was exciting and fun. From then on, I knew what I wanted to be."

Though he went to law school at the University of Havana (where one of his fellow students was Fidel Castro), he pursued his true interest even there, making two films for the Cuban Communist Party. He wasn't a party member at that time, but was responding to a culture of student activism that had dominated his campus for the previous three decades.

In 1951 Gutiérrez Alea went to Rome to continue his studies at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia. He arrived just after the peaking of post-war neorealism, of which his new school was still very much a center of influence. One of his fellow students was Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Returning to Cuba two years later, the future director found minimal opportunity to pursue his profession, but a fertile landscape for his political and social activism. In his absence the country had been come under the military dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista.

Gutiérrez Alea joined a group making a clandestine, neorealistinspired film about charcoal burners, intended to expose the conditions imposed on the poor by American neocolonialism. The film, El Megano , which took a year to make, was shown once, at a 1956 screening on the University of Havana campus. It was then seized by the authorities, and the filmmakers were interrogated. That same year Gutiérrez Alea finally found paid work as a filmmaker, making short documentaries and humorous films for a weekly TV series called Cinerevista. He worked for a Mexican producer named Manuel Barbachano Ponce, who two years later would produce Luis Buñuel's Nazarin .

After Castro came to power on December 31, 1958, Alea was recruited by the Cultural Directorate of the Rebel Army to make a documentary called Esta tierra nuestra ( This Land of Ours ). Meanwhile, the Revolutionary Government was establishing an official film production house called the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry; it's first head was Alfredo Guevara, who had been involved in the making of El Megano . Gutiérrez Alea became one of its founding members.

Over the next eight years, Gutiérrez Alea made another documentary and three feature films, including a satire on revolutionary excess called La muerte de un burócrata ( Death of a Bureaucrat ). Then in 1968 he began work on what was to become his most influential films, Memorias de subdesarollo ( Memories of Underdevelopment ).

Based on a novella by Edmundo Desnoes called Inconsolable Memories , Gutiérrez Alea's film combined its fictional elements with documentary footage to create a portrait of a bourgeois intellectual who wants to be a part of the revolutionary ferment going on all around him, but remains disconnected, watching the transformation of Havana society through binoculars from his apartment balcony. This breaking down of the barriers between fiction and reality was widely exploited in the Cuban film industry, and was to have a wide influence on world cinema when it was finally shown in America and France in 1973 and 1974.

In America the National Society of Film Critics honored Memorias de subdesarollo by inviting its director to a ceremony to accept a plaque and a $2000 award. The U.S. State Department refused to grant Gutiérrez Alea a visa, and threatened the Society with legal action if it delivered the award in any other way. The New York Times editorialized on the situation on January 19, 1974: "The absurdity of such sanctions must be measured against the fact that the USA is now busily encouraging trade with the Communist superpowers. But the transmission of a prize for cultural achievement is treated as a subversive act . . . At a time when détente with the Soviet Union and the normalization of relations with Communist China are rightfully considered diplomatic triumphs, the suggestion that Cuban filmmakers might constitute a menace only exposes American officialdom to ridicule."

While Gutiérrez Alea always defended the Cuban revolution abroad, he also accepted the responsibility of critiquing it at home. This dual response is exemplified by the way he responded to the issues of oppression experienced by gay men and lesbians under the Castro regime. In 1984 the director participated over several issues of the Village Voice in a polemical discussion with Cuban expatriate cinematographer Nestor Almendros. This was in response to Almendros' documentary about the official anti-gay oppression in Cuba called Improper Conduct .

Gutiérrez Alea forthrightly defended the Cuban regime against what he viewed as Almendros' "half-truths," and tried to place the attitudes against homosexuality in a wider context of Cuba's Catholic and Spanish traditions. Working in Cuba however, Gutiérrez Alea had already made one film, Hasta un cierto punto ( Up to a Certain Point ), which analyzed the machismo underlying anti-gay prejudice, and in 1993 he would produce a film, Frese y chocolate ( Strawberry and Chocolate ) which brought the issue to the forefront of political debate in Cuba.

Because of deteriorating health, Gutiérrez Alea had to bring in a frequent collaborator, Juan Carlos Tabío, to co-direct this film. Tabío also served in the same capacity on Gutiérrez Alea's final project, Guantanamera . The director succumbed to lung cancer on April 16, 1996, at the age of 67. He was widely eulogized as the brightest star of the Cuban cinema, at a time when it was matched in the hemisphere only by Brazil in its artistic excellence and social and political relevance.

—Stephen Brophy

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: