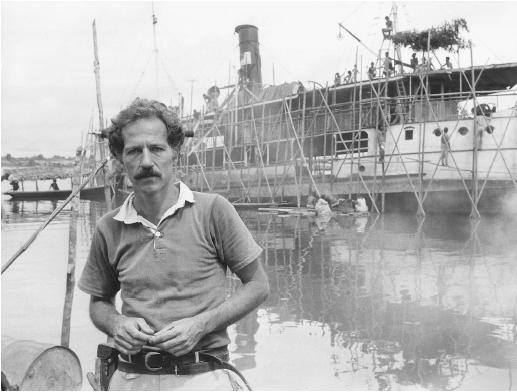

Werner Herzog - Director

Nationality: German. Born: Werner Stipetic in Sachrang, 5 September 1942. Education: Classical Gymnasium, Munich, until 1961; University of Munich, early 1960s. Family: Married journalist Martje Grohmann, one son. Career: Worked as a welder in a steel factory for U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration; founded Werner Herzog Filmproduktion, 1966; walked from Munich to Paris to visit film historian Lotte Eisner, 1974. Awards: Bundesfilmpreis, and Silver Bear, Berlinale, for Signs of Life , 1968; Bundespreis, and Special Jury Prize, Cannes Festival, for Every Man for Himself and God against All , 1975; Best Director, Cannes Festival, for Fitzcarraldo , 1982. Address: Turkenstr. 91, D-80799 Münich, Germany.

Films as Director (beginning 1966, films are produced or co-produced by Werner Herzog Filmproduktion)

- 1962

-

Herakles (+ pr, sc)

- 1964

-

Spiel im Sand ( Game in the Sand ) (unreleased) (+ pr, sc)

- 1966

-

Die beispiellose Verteidigung der Festung Deutschkreuz ( The Unprecedented Defense of the Fortress of Deutschkreuz ) (+ pr, sc)

- 1967

-

Lebenszeichen ( Signs of Life ) (+ sc, pr)

- 1968

-

Letzte Worte ( Last Words ) (+ pr, sc); Massnahmen gegen Fanatiker ( Precautions against Fanatics ) (+ pr, sc)

- 1969

-

Die fliegenden Ärzte von Ostafrika ( The Flying Doctors of East Africa ) (+ pr, sc); Fata Morgana ( Mirage ) (+ sc, pr)

- 1970

-

Auch Zwerge haben klein angefangen ( Even Dwarfs Started Small ) (+ pr, sc, mu arrangements); Behinderte Zukunft ( Handicapped Future ) (+ pr, sc)

- 1971

-

Land des Schweigens und der Dunkelheit ( Land of Silence and Darkness ) (+ pr, sc)

- 1972

-

Aguirre, der Zorn Göttes ( Aguirre, the Wrath of God ) (+ pr, sc)

- 1974

-

Die grosse Ekstase des Bildschnitzers Steiner ( The Great Ecstasy of the Sculptor Steiner ) (+ pr, sc); Jeder für sich und Gott gegen alle ( Every Man for Himself and God against All ; The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser ) (+ pr, sc)

- 1976

-

How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck (+ pr, sc); Mit mir will keiner spielen ( No One Will Play with Me ) (+ pr, sc); Herz aus Glas ( Heart of Glass ) (+ pr, co-sc, bit role as glass carrier)

- 1977

-

La Soufrière (+ pr, sc, narration, appearance)

- 1978

-

Stroszek (+ pr, sc)

- 1979

-

Nosferatu—Phantom der Nacht ( Nosferatu, the Vampire ) (+ pr, sc, bit role as monk); Woyzeck (+ pr, sc)

- 1980

-

Woyzeck ; Glaube und Währung ( Creed and Currency )

- 1981

-

Fitzcarraldo (+ pr, sc)

- 1983

-

Where the Green Ants Dream ( Wo Die Grünen Ameisen Traümen )

- 1984

-

Ballade vom Kleinen Soldaten ( Ballad of the Little Soldier ); Gasherbrum—Der leuchtende Berg ( Gasherbrum—The Dark Glow of the Mountains )

- 1987

-

Cobra Verde (+ sc)

- 1988

-

Wodaabe—Die Hirten der Sonne ( Herdsmen of the Sun ); Les Gaulois ( The French )

- 1989

-

Es ist nicht leicht ein Gott zu sein ( It Isn't Easy Being God )

- 1990

-

Echos aus Einem Dustern Reich ( Echoes from a Somber Kingdom )

- 1991

-

Schrie aus Stein ( Scream of Stone ); Jag Mandir ( The Eccentric Private Theatre of the Maharajah of Udaipur )

- 1992

-

Lektionen in Finsternis ( Lessons of Darkness )

- 1993

-

Bells from the Deep ( Glocken aus der Tiefe )

- 1994

-

Die Verwandlung der Welt in Musik ( The Transformation of the World into Music )

- 1995

-

Tod für fünf Stimmen ( Death for Five Voices ) (+ sc)

- 1997

-

Little Dieter Needs to Fly (+ sc, Narrator)

- 1999

-

Mein liebster Feind—Klaus Kinski

- 2000

-

Invincible (+ co-sc)

Publications

By HERZOG: books—

Werner Herzog: Drehbücher I , Munich, 1977.

Werner Herzog: Drehbücher II , Munich 1977.

Sur le chemin des glaces: Munich-Paris du. 23.11 au 14.12.1974 , Paris, 1979.

Werner Herzog: Stroszek, Nosferatu: Zwei Filmerzählungen , Munich, 1979.

Screenplays , New York, 1980.

Fitzcarraldo: The Original Story , Seattle, 1983.

Cobra Verde , Munich, 1987.

Vom Gehen im Eis (Of Walking in Ice) , London, 1994.

By HERZOG: articles—

"Rebellen in Amerika," in Filmstudio (Frankfurt), May 1964.

"Neun Tage eines Jahres," in Filmstudio (Frankfurt), September 1964.

"Mit den Wölfen heulen," in Filmkritik (Munich), July 1968.

"Warum ist überhaupt Seiendes und nicht vielmehr Nichts?," in Kino (West Berlin), March/April 1974.

Interview with S. Murray, in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), December 1974.

"Every Man for Himself," interview with D. L. Overbey, in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1975.

Interview with Michel Ciment, in Positif (Paris), May 1975.

L'Énigme de Kaspar Hauser , on cutting continuity and dialogue, in Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), June 1976.

"Signs of Life: Werner Herzog," interview with Jonathan Cott, in Rolling Stone (New York), 18 November 1976.

Aguirre, la colère de Dieu , on cutting continuity and dialogue, in Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), 15 June 1978.

"I Feel That I'm Close to the Center of Things," interview with L. O'Toole, in Film Comment (New York), November/December 1979.

Interview with B. Steinborn and R. von Naso, in Filmfaust (Frankfurt), February/March 1982.

Interview with G. Bechtold and G. Griksch, in Filmfaust (Frankfurt), October/November 1984.

Interview in Time Out (London), 20 April 1988.

"Io e il mio cinema," in Filmcritica (Siena), March 1990.

Interview with Bion Steinborn, in Filmfaust (Frankfurt am Main), July-October 1990.

Interview with Z. Nevelõs and P. Sneé, in Filmkultura (Budapest), June 1994.

"Operní patos a Blaise Pascal. Rozhovor s Wernerem Herzogem," an interview with Tomáš Liška, in Film a Doba (Prague), Winter 1994.

"L'enfer vert," an interview with Bernard Génin and others, in Télérama (Paris), 5 April 1995.

On HERZOG: books—

Greenberg, Alan, Heart of Glass , Munich, 1976.

Schütte, Wolfram, and others, Herzog/Kluge/Straub , Vienna, 1976.

Franklin, James, New German Cinema: From Oberhausen to Hamburg , Boston, 1983.

Phillips, Klaus, editor, New German Filmmakers: From Oberhausen through the 1970s , New York, 1984.

Corrigan, Timothy, The Films of Werner Herzog: Between Mirage and History , New York, 1986.

Elsaesser, Thomas, New German Cinema: A History , London, 1989.

Murray, Bruce A., and Christopher J. Wickham, editors, Framing the Past: The Historiography of German Cinema and Television , Carbondale, Illinois, 1992.

On HERZOG: articles—

"Herzog Issue" of Cinema (Zurich), vol. 18, no. 1, 1972.

Wetzel, Kraft, "Werner Herzog," in Kino (West Berlin), April/May 1973.

Bachmann, Gideon, "The Man on the Volcano," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Autumn 1977.

Dorr, John, "The Enigma of Werner Herzog," in Millimeter (New York), October 1977.

Walker, B., "Werner Herzog's Nosferatu ," in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1978.

Andrews, N., "Dracula in Delft," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), October 1978.

Morris, George, "Werner Herzog," in International Film Guide 1979 , London, 1978.

Cleere, E., "Three Films by Werner Herzog," in Wide Angle (Athens, Ohio), vol. 3, no. 4, 1980.

Van Wert, W.F., "Hallowing the Ordinary, Embezzling the Everyday: Werner Herzog's Documentary Practice," in Quarterly Review of Film Studies (Pleasantville, New York), Spring 1980.

Davidson, D., "Borne out of Darkness: The Documentaries of Werner Herzog," in Film Criticism (Edinboro, Pennsylvania), Fall 1980.

"Werner Herzog," in Film Dope (London), March 1982.

Goodwin, M., "Herzog the God of Wrath," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), June 1982.

Carroll, Noel, "Herzog, Presence, and Paradox," in Persistence of Vision (Maspeth, New York), Fall 1985.

Kennedy, Harlan, "Amazon Grace," in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1986.

Davidson, David, "Borne out of Darkness: The Documentaries of Werner Herzog," in Film Criticism (Meadville, Pennsylvania), no. 1/2, 1987.

Mouton, Jan, "Werner Herzog's Stroszek : A Fairy-Tale in an Age of Disenchantment," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 15, no. 2, 1987.

Caltvedt, Lester, "Herzog's Fitzcarraldo and the Rubber Era," in Film and History (New York), vol. 18, no. 4, 1988.

"Herzog Issue" of Post Script (Jacksonville, Florida), Summer 1988.

Elsaesser, Thomas, "Werner Herzog: Tarzan Meets Parsifal," in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), May 1988.

Stiles, Victoria M., "Fact and Fiction: Nature's Endgame in Werner Herzog's Aguirre, the Wrath of God ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), July 1989.

Uhrík, Štefan, "Werner Herzog o ryzyku filmowania," in Kino (Warsaw), July 1991.

Pezzotta, Alberto, "La realtà e il mito," in Filmcritica (Siena), May 1992.

Klerk, Nico de, and others, "De helden van de jaren zeventig," in Skrien (Amsterdam), June-July 1992.

Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), November 1993.

Andrew, Geoff, "Plight Relief," in Time Out (London), 17 April 1996.

Hogue, Peter, "Genre-busting. Documentaries as Movies," in Film Comment (New York), July-August 1996.

Stiles, Victoria M., "Woyzeck in Focus: Werner Herzog and His Critics," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), vol. 24, no. 3, 1996.

Wiberg, Matts, in Filmhäftet (Stockholm), vol. 26, no. 104, 1998.

McCarthy, Todd, "My Best Friend (Mein liebster Feind)," in Variety (New York), 24 May 1999.

On HERZOG: films—

Weisenborn, Christian, and Erwin Keusch, Was ich bin sind meine Filme , Munich, 1978.

Blank, Les, Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe , U.S., 1980.

Blank, Les, Burden of Dreams , U.S., 1982.

* * *

Werner Herzog, more than any director of his generation, has through his films embodied German history, character, and cultural richness. While references to verbal and other visual arts would be out of place in treating most film directors, they are key to understanding Herzog. For his techniques he reaches back into the early part of the twentieth century to the Expressionist painters and filmmakers; back to the Romantic painters and writers for the luminance and allegorization of landscape and the human figure; even further beyond into sixteenth-century Mannerist extremes of Mathias Günwald; and throughout his nation's heritage for that peculiarly Germanic grotesque. In all these technical and expressive veins, one finds the qualities of exaggeration, distortion, and the sublimation of the ugly.

More than any, "grotesque" presents itself as a useful term to define Herzog's work. His use of an actor like Klaus Kinski, whose singularly ugly face is sublimated by Herzog's camera, can best be described by such a term. Persons with physical defects like deafness and blindness, and dwarfs, are given a type of grandeur in Herzog's artistic vision. Herzog, as a contemporary German living in the shadow of remembered Nazi atrocities, demonstrates a penchant for probing the darker aspects of human behavior. Herzog's vision renders the ugly and horrible sublime, while the beautiful is omitted and, when included, destroyed or made to vanish (like the beautiful Spanish noblewoman in Aguirre) .

Closely related to the grotesque in Herzog's films is the influence of German expressionism on him. Two of Herzog's favorite actors, Klaus Kinski and Bruno S., have been compared to Conrad Veidt and Fritz Kortner, prototypical actors of German expressionistic dramas and films during the teens and 1920s. Herzog's actors make highly stylized, indeed often stock, gestures; in close-ups, their faces are set in exaggerated grimaces.

The characters of Herzog's films often seem deprived of free will, merely reacting to an absurd universe. Any exertion of free will in action leads ineluctably to destruction, death, or at best frustration by the unexpected. The director is a satirist who demonstrates what is wrong with the world but, as yet, seems unable or unwilling to articulate the ways to make it right; indeed, one is at a loss to find in his world view any hope, let alone prescription, for improvement.

Herzog's mode of presentation has been termed by some critics as romantic and by others as realistic. This seeming contradiction can be resolved by an approach that compares him with those Romantic artists who first articulated elements of the later realistic approach. Critics have found in the quasi-photographic paintings of Caspar David Friedrich an analogue for Herzog's super-realism. As with these artists, there is an aura of unreality in Herzog's realism. Everything is seen through a camera that rarely goes out of intense, hard focus. Often it is as if his camera is deprived of the normal range of human vision, able only to perceive part of the whole through a telescope or a microscope.

In this strange blend of romanticism and realism lies the paradoxical quality of Herzog's talent: he, unlike Godard, Resnais, or Altman, has not made great innovations in film language; if his style is to be defined at all it is as an eclectic one; and yet, his films do have a distinctive stylistic quality. He renders the surface reality of things with such an intensity that the viewer has an uncanny sense of seeing the essence beyond. Aguirre , for example, is unrelenting in its concentration on filth, disease, and brutality; and yet it is also an allegory which can be read on several levels: in terms of Germany under the Nazis, America in Vietnam, and more generally on the bestiality that lingers beneath the facade of civilized conventions. In one of Herzog's romantic tricks within his otherwise realistic vision, he shows a young Spanish noblewoman wearing an ever-pristine velvet dress amid mud and squalor; further, only she of all the rest is not shown dying through violence and is allowed to disappear almost mystically into the dense vegetation of the forest: clearly, she represents that transcendent quality in human nature that incorruptibly endures. This figure is dropped like a hint to remind us to look beyond mere surface.

One finds, however, in Fitzcarraldo , Herzog's supreme apotheosis of the spiritual dimensions of the rain forest. As much in the production as in the substance of the film, the Western Imperialist will to reshape the wilderness is again and again met with reversals that render that will meaningless. The protagonist's titanic effort to get a riverboat over a hill from one river to another is achieved only to be thwarted by the natives who cut the ropes, sending it careening downstream through the rapids in a sacrifice to their river deity. The boat ends up uselessly back where it began: a massive symbol of human futility. Only the old gramophone shown playing records of Caruso throughout the jungle voyage offers—like the Spanish noblewoman in Aguirre —Herzog's vision of beauty that rarely escapes being rendered meaningless by an otherwise absurd universe.

Herzog's Australian film Where Green Ants Dream does penance for any taint of Western Imperialism that Fitzcarraldo might have given him. The director comes down hard against the modern way of life. This film is saved from tendentiousness by movements of human comedy through which a very sympathetic hero learns from the Native Australians, and by Herzog's much-loved 360-degree pans over the flatness of the Outback. This technique is also used by Herzog to convey the sense of flat immensity of sub-Saharan Africa in Herdsmen of the Sun , a lyrical celebration of the Wodaabe tribesmen, who bend Western gender expectations by having the men and women reverse roles in courtship. Here, too, Herzog evidences his German heritage by following in the African footsteps of his greatest—if most problematic—filmmaking compatriot: Leni Riefenstahl, whose last work was a documentary of a sub-Saharan tribe to the east of the Wodaabe.

—Rodney Farnsworth

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: