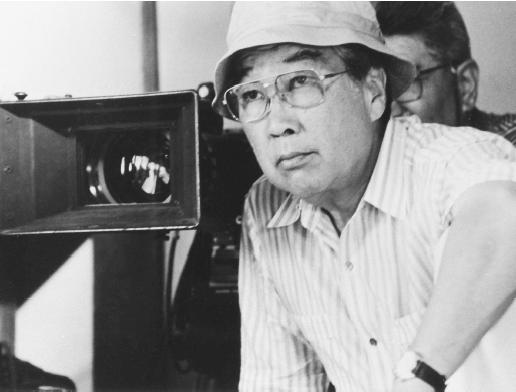

Shohei Imamura - Director

Nationality: Japanese. Born: Tokyo, 1926. Education: Educated in technical school, Tokyo, until 1945; studied occidental history at Waseda University, Tokyo, graduated 1951. Career: Assistant director at Shochiku's Ofuna studios, 1951; moved to Nikkatsu studios, 1954; assistant to director Yuzo Kawashima, 1955–58; directed first film, Nusumareta yokuju , 1958; formed Imamura Productions, 1965; worked primarily for TV, from 1970; founder and teacher, Yokohama Broadcast Film Institute. Awards: Palme d'Or, Cannes Festival, for The Ballad of Narayama , 1983.

Films as Director:

- 1958

-

Nusumareta yokujo ( Stolen Desire ); Nishi Ginza eki mae ( Lights of Night ; Nishi Ginza Station ) (+ sc); Hateshinaki yokubo ( Endless Desire ) (+ co-sc)

- 1959

-

Nianchan ( My Second Brother ; The Diary of Sueko ) (+ co-sc)

- 1961

-

Buta to gunkan ( The Flesh Is Hot ; Hogs and Warships ) (+ co-sc)

- 1963

-

Nippon konchuki ( The Insect Woman ) (+ co-sc)

- 1964

-

Akai satsui ( Unholy Desire ; Intentions of Murder ) (+ co-sc)

- 1966

-

Jinruigaku nyumon ( The Pornographers: Introduction to Anthropology ) (+ co-sc, pr)

- 1967

-

Ningen johatsu ( A Man Vanishes ) (+ sc, role, pr)

- 1968

-

Kamigami no fukaki yokubo ( The Profound Desire of the Gods ; Kuragejima: Tales from a Southern Island ) (+ co-pr, co-sc)

- 1970

-

Nippon sengoshi: Madamu Omboro no seikatsu ( History of Postwar Japan as Told by a Bar Hostess ) (+ co-pr, planning, role as interviewee)

- 1975

-

Karayuki-san ( Karayuki-san, the Making of a Prostitute ) (for TV) (+ co-pr, planning)

- 1979

-

Fukushu suruwa ware ni ari ( Vengeance Is Mine )

- 1980

-

Eijanaika ( Why Not? ) (+ co-sc)

- 1983

-

Narayama bushi-ko ( The Ballad of Narayama )

- 1987

-

Zegen ( The Pimp )

- 1988

-

Kuroi Ame ( Black Rain )

- 1997

-

Unagi ( The Eel ) (+ co-sc)

- 1998

-

Kanzo Sensei ( Dr. Akagi ) (+ co-sc)

Other Films:

- 1951

-

Bakushu ( Early Summer ) (Ozu) (asst d)

- 1952

-

Ochazuke no aji ( The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice ) (Ozu) (asst d)

- 1953

-

Tokyo monogatari ( Tokyo Story ) (Ozu) (asst d)

- 1954

-

Kuroi ushio ( Black Tide ) (Yamamura) (asst d)

- 1955

-

Tsukiwa noborinu ( Moonrise ) (Tanaka) (asst d)

- 1956

-

Fusen ( The Balloon ) (Kawashima) (co-sc)

- 1958

-

Bakumatsu Taiyoden ( Saheiji Finds a Way ; Sun Legend of the Shogunate's Last Days ) (Kawashima) (co-sc)

- 1959

-

Jigokuno magarikago ( Turning to Hell ) (Kurahara) (co-sc)

- 1962

-

Kyupora no aru machi ( Cupola Where the Furnaces Glow ) (Uravama) (sc)

- 1963

-

Samurai no ko ( Son of a Samurai ; The Young Samurai ) (Wakasugi) (co-sc)

- 1964

-

Keirin shonin gyojoki (Nishimira) (co-sc)

- 1967

-

Neon taiheiki-keieigaku nyumon ( Neon Jungle ) (Isomi) (co-sc)

- 1968

-

Higashi Shinaki ( East China Sea ) (Isomi) (story, co-sc)

Publications

By IMAMURA: book—

Sayonara dake ga jinsei-da [Life Is Only Goodbye: Biography of Director Yuzo Kawashima], Tokyo, 1969.

By IMAMURA: articles—

"Monomaniaque de l'homme. . . ," in Jeune Cinéma (Paris), November 1972.

Interview with S. Hoass, in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), September/October 1981.

Interview with Max Tessier, in Revue du Cinéma (Paris), September 1983.

Interview with C. Tesson, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), November 1987.

Interview in Revue du Cinéma/Image et Son (Paris), November 1989.

"Silence de Mort," an interview with Gérard Pangon, in Télérama (Paris), 26 July 1995.

Interview with Yann Tobin and Hubert Niogret, in Positif (Paris), October 1997.

Interview with Pierre Eisenreich and Hubert Niogret, in Positif (Paris), December 1998.

"Dr. Akagi: Kanzo Sensei," an interview with Freddy Sartor, in Film en Televisie + Video (Brussels), January 1999.

On IMAMURA: books—

Imamura Shohei no eiga [The Films of Shohei Imamura], Tokyo, 1971.

Mellen, Joan, Voices from the Japanese Cinema , New York, 1975.

Sugiyama, Heiichi, Sekai no eiga sakka 8: Imamura Shohei [Film Directors of the World 8: Shohei Imamura], Tokyo, 1975.

Bock, Audie, Japanese Film Directors , New York, 1978; revised edition, Tokyo, 1985.

Tessier, Max, editor, Le Cinéma japonais au present: 1959–1979 , Paris, 1980.

Richie, Donald, with Audie Bock, Notes for a Study on Shohei Imamura , Bergamo, 1987.

Piccardi, Adriano, and Angelo Signorelli, Shohei Imamura , Bergamo, 1987.

Quandt, James, editor, Shohei Imamura , Bloomington, 1999.

On IMAMURA: articles—

Yamada, Koichi, "Les Cochons et les dieux: Imamura Shohei," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), May/June 1965.

"Dossier on Imamura," in Positif (Paris), April 1982.

Gillett, John, "Shohei Imamura," in Film Dope (London), January 1983.

Casebier, A., "Images of Irrationality in Modern Japan: The Films of Shohei Imamura," in Film Criticism (Edinboro, Pennsylvania), Fall 1983.

Kehr, Dave, "The Last Rising Sun," in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1983.

"Imamura Section" of Positif (Paris), May 1985.

Baecque, Antoine de, "Histoire de douleur," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), November 1989.

Baecque, Antoine de, "Le meurtre du cochon rose," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), April 1990.

Boquet, Stéphane, "Imamura, le porc et son homme," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), April 1997.

* * *

Outrageous, insightful, sensuous, and great fun to watch, the films of Shohei Imamura are among the greatest glories of postwar Japanese cinema, yet Imamura remains largely unknown outside of Japan. Part of the reason, to be sure, lies in the fact that Imamura has until recently worked for small studios such as Nikkatsu or on his own independently financed productions. But it may also be because Imamura's films fly so furiously in the face of what most Westerners have come to expect of Japanese films.

After some amateur experience as a theater actor and director, Imamura joined Shochiku Studios in 1951 as an assistant director, where he worked under, among others, Yasujiro Ozu. His first important work, My Second Brother , an uncharacteristically gentle tale set among Korean orphans living in postwar Japan, earned him third place in the annual Kinema Jumpo "Best Japanese Film of the Year" poll, and from then on Imamura's place within the Japanese industry was established. Between 1970 and 1978, Imamura "retired" from feature filmmaking, concentrating his efforts instead on a series of remarkable television documentaries that explored little-known sides of postwar Japan. In 1978, Imamura returned to features with his greatest commercial and critical success, Vengeance Is Mine , a complex, absorbing study of a cold-blooded killer. In 1983, his film The Ballad of Narayama was awarded the Gold Palm at the Cannes Film Festival, symbolizing Imamura's belated discovery by the international film community.

Imamura has stated that he likes to make "messy films," and it is the explosive, at times anarchic quality of his work that makes him appear "uncharacteristically Japanese" when seen in the context of Ozu, Mizoguchi, or Kurosawa. Perhaps no other filmmaker anywhere has taken up Jean-Luc Godard's challenge to end the distinction between "documentary" and "fiction" films. In preparation for filming, Imamura will conduct exhaustive research on the people whose story he will tell, holding long interviews to extract information and to become familiar with different regional vocabularies and accents (many of his films are set in remote regions of Japan). Insisting always on location shooting and direct sound, Imamura has been referred to as the "cultural anthropologist" of the Japanese cinema. Even the titles of some of his films— The Pornographers: Introduction to Anthropology and The Insect Woman (whose Japanese title literally translates to "Chronicle of a Japanese Insect")—seem to reinforce the "scientific" spirit of these works. Yet, if anything, Imamura's films argue against an overly clinical approach to understanding Japan, as they often celebrate the irrational and instinctual aspects of Japanese culture.

Strong female protagonists are usually at the center of Imamura's films, yet it would be difficult to read these films as "women's films" in the way that critics describe works by Mizoguchi or Naruse. Rather, women in Imamura's films are always the ones more directly linked to "ur-Japan,"—a kind of primordial fantasy of Japan not only preceeding "westernization" but before any contact with the outside world. In The Profound Desire of the Gods , a brother and sister on a small southern island fall in love and unconsciously attempt to recreate the myth of Izanagi and Izanami, sibling gods whose union founded the Japanese race. Incest, a subject which might usually be seen as shocking, is treated as a perfectly natural expression, becoming a crime only due to the influence of "westernized" Japanese who have come to civilize the island. Imamura's characters indulge freely and frequently in sexual activity, and sexual relations tend to act as a kind of barometer for larger, unseen social forces. The lurid, erotic spectacles in Eijanaika , for example, are the clearest indication of growing frustrations that finally explode in massive riots in the film's conclusion.

—Richard Peña

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: