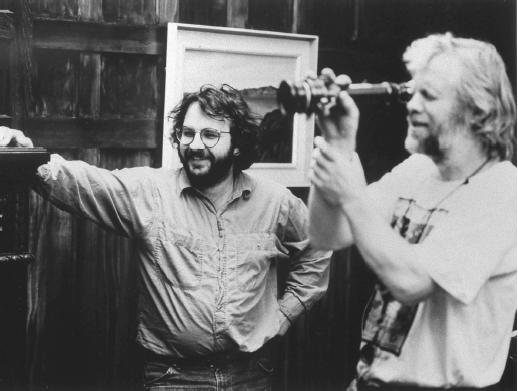

Peter Jackson - Director

Nationality:

New Zealander.

Born:

Wellington, New Zealand, 30 October 1961.

Family:

Unmarried; current partner co-screenwriter Fran Walsh.

Career:

Started making films when given Super 8-millimeter camera by parents at

age eight; made amateur fiction shorts, including

The Dwarf Patrol

,

Curse of the Gravewalker

,

The Valley;

left school at age seventeen, failed to get job in film industry, joined

local newspaper as photo-engraving apprentice; named top New Zealand

photo-engraving apprentice three years running; bought 16-millimeter

Bolex, 1983; started making feature film

Roast of the Day

on weekends with friends and colleagues; renamed

Bad Taste

, film took four years to shoot; finally completed after funding received

from New Zealand Film Commission, 1986, enabling Jackson to quit newspaper

job for full-time filmmaking; set up own studio, Wingnut Films, in

Wellington, with computer-driven special effects division, WETA; after

three low-budget features, international acclaim for

Heavenly Creatures

led to deal with Universal to make next project in New Zealand with U.S.

funding.

Awards:

Metro Media Award, Toronto, and Silver Lion, Venice, both 1994, and Oscar

nomination, Best Screenplay, 1995, all for

Heavenly Creatures.

Agent:

UTA, 9560 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 500, Beverly Hills, CA 90212, U.S.A.

Films as Director and Co-Screenwriter:

- 1987

-

Bad Taste (+ pr, ph, ed, multiple roles)

- 1989

-

Meet the Feebles (+ pr)

- 1992

-

Braindead

- 1994

-

Heavenly Creatures

- 1995

-

Frighteners (+ pr)

- 1996

-

Forgotten Silver (+ co-sc)

- 2001

-

Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (+ co-sc, pr)

- 2002

-

Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (+ co-sc)

- 2003

-

Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (+ co-sc)

Other Films:

- 1995

-

Jack Brown, Genius (Hiles) (sc, 2nd unit d, exec pr); Good Taste (interviewee)

Publications

By JACKSON: articles—

"Meet the Feebles," interview with Alan Jones in Starburst (London), May 1991.

"Peter Jackson: Heavenly Creatures ," interview in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), April 1994.

"Gut Reaction," an interview with Tom Charity, in Time Out (London), 25 January 1995.

"Earthly Creatures," an interview with Michael Atkinson, in Film Comment (New York), May-June 1995.

" Heavenly Creatures : Writing and Directing Heavenly Creatures ," an interview with Frances Walsh, Peter Jackson, and Tod Lippy, in Scenario , Fall 1995.

"Cryptically Acclaimed," an interview with Michael Helms, in Cinema Papers (Fitzroy), December 1996.

"Scary Rollercoaster Ride," an interview with P. Wakefield, in Onfilm (Auckland), no. 11, 1996–1997.

"Realismens fiende," an interview with Kari Andresen, in Chaplin (Stockholm), vol. 39, no. 1, 1997.

"Pure fantasie," an interview with Ronnie Pede and Piet Goethals, in Film en Televisie + Video (Brussels), February 1997.

"It Was Close Enough, Jim," in Onfilm (Auckland), no. 10, 1997.

On JACKSON: articles—

Clarke, Jeremy, "Talent Force," in Films & Filming (London), September 1989.

Clarke, Jeremy, "Photolithographers from Outer Space," in What's on in London , 13 September 1989.

Floyd, Nigel, "Kiwi Fruit," in Time Out (London), 12 May 1993.

Maxford, Howard, "Gore Blimey!," in What's On in London , 12 May 1993.

McDonald, Lawrence, "A Critique of the Judgement of Bad Taste or beyond Braindead Criticism: The Films of Peter Jackson," in Illusions (Wellington, NZ), Winter 1993.

Salisbury, Mark, "Peter Jackson, Gore Hound," in Empire (London), June 1993.

Feinstein, Howard, "Death and the Maidens," in Village Voice (New York), 15 November 1994.

Charity, Tom, "Gut Reaction," in Time Out (London), 25 January 1995.

Cameron-Wilson, James, "Natural-born Culler," in Times (London), 8 February 1995.

Cameron-Wilson, James, "The Frightener," in What's on in London , 8 February 1995.

Atkinson, Michael, "Earthly Creatures," in Film Comment (New York), May/June 1995.

Williams, David E., and Ron Magid, "Scared Silly: New Zealand's New Digital Age," in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), August 1996.

Filmography, in Segnocinema (Vicenza), January/February 1997.

Grapes, D., "Filmmakers Aim Broadsides at 'Passionate' Commission," in Onfilm (Auckland), no. 10, 1997.

* * *

After his first three features, most critics thought they had Peter Jackson neatly pegged: an antipodean maverick whose films made up for their zero-budget limitations with comic gusto and creative ingenuity; films whose gross-out excesses of spurting bodily fluids and splattered guts made George Romero and Sam Raimi look like models of genteel restraint. Jackson's work, in short, seemed to be comprehensively summed up by the blithely upfront title of his debut film, Bad Taste. And then came his fourth film, the award-winning Heavenly Creatures , and suddenly all the assumptions had to be revised. Jackson himself, noting a hint of surprise behind the acclaim, pointed out that like all his work the film stemmed from his "unhealthy interest in the grotesque." But if there was continuity in terms of themes and preoccupations, Heavenly Creatures showed Jackson was also capable of emotional complexity, subtlety, and sophistication—qualities no one would have suspected from his previous films.

Far from striving to disguise the ramshackle, garden-shed genesis of his early work, Jackson gloried in it, making an amateurish, peculiarly New Zealander domesticity central to his humour. The Astral Investigation and Defence Service team ("I wish they'd do something about those initials") who foil predatory aliens in Bad Taste are as far from their jut-jawed Hollywood counterparts as could be imagined; inept, nerdish, and post-adolescent, they shamble around bickering over trivialities or moaning about filling in time-sheets. In Braindead , whose showdown erupts in a bland suburban home, the hero demolishes a horde of flesh-eating zombies, not with flamethrower or pump-action shotgun, but with a rotary lawnmower—"a Kiwi icon," according to the director. It comes as no surprise to read, in the end-titles for Bad Taste , a credit to "Special Assistants to the Producer (Mum and Dad)."

Both Bad Taste and Braindead (whose farcical brand of ultra-physical violence Jackson dubs "splatstick") spoof well-established and much-parodied formulas within the horror genre, respectively the space-invaders movie and the zombie movie. Meet the Feebles is more audacious in its choice of target: the hitherto sacrosanct world of Jim Henson's Muppets. Hijacking the standard Muppet narrative framework of backstage shenanigans, Jackson gleefully subverts the perky ethos of the puppet troupe with lavish helpings of booze, filth, sex, and drugs, culminating in one of his trademark bloodbaths. He also pushes the unstated logic of Muppetry to ends that Henson would shudder to confront; if Miss Piggy can get the hots for Kermit, why shouldn't an elephant have sex with a chicken? (The resultant outlandish hybrid is wheeled on—literally—for our delectation.) Jackson further outrages Muppet conventions by making the frog character in his film a Vietnam vet with a heroin habit, while Kermit's counterpart as stage director is an effete, English-accented fox who mounts a big production number in praise of sodomy.

This fascination with outrage, with the consequences of pushing beyond the bounds of convention, carries through into Heavenly Creatures , Jackson's finest film to date. Based on an actual New Zealand cause celèbre of the 1950s, the Parker-Hulme case, the film traces the progress of two fifteen-year-old schoolgirls into an increasingly unhinged world of ritual and fantasy. Instinctive loners, Pauline and Juliet bond together to turn their outsider status into an exclusive, hermetic society tinged with lesbianism and peopled by personal icons—Mario Lanza, James Mason—along with figures from their medieval fantasy kingdom of Borovnia. Drawing on real case documents (Pauline's diaries and the girls' own Borovnian "novels"), Jackson creates a mood of intense pubescent obsession sliding steadily out of control until—as the borders between the two worlds elide—it culminates in brutal murder.

Determined not to present his heroines as the "evil lesbian killers" they were branded by contemporary press accounts, Jackson not only portrays them with sympathy and insight, but captures the richly creative energy of their shared fantasies. Their behaviour is seen as a reaction to the imagination-starved society around them, since 1950s Christchurch, all garish pastels and agonised gentility, appears no less bizarre and unbalanced a world (and a whole lot less fun) than the one the girls create for themselves. Yet the killing—of Pauline's uncomprehending, well-meaning mother—shares none of the sick-joke relish of Jackson's previous films; it is shown as clumsy, painful, and distressing.

Jackson firmly denies that Heavenly Creatures represents a bid to be seen as a "serious filmmaker" who wants to do "arty mainstream films." "People immediately assume that filmmakers do things because of a grand plan. . . . I do intend to do other splatter films," he told Cinema Papers. "I have intentions of doing all sorts of films. I have no interest in a 'career' as such." As if to prove it, he reverted to splatstick mode with The Frighteners , an Evil-Dead -style horror-comedy made (thanks to backing from Universal) on a less shoestring basis than his earlier films.

Jackson's achievement in staying put at home and persuading the Hollywood money to come to him bodes well for his country's film industry. Most successful New Zealand directors (Roger Donaldson, Geoff Murphy, Jane Campion, Lee Tamahori) have used their first major hit as a springboard for Hollywood. Jackson, remaining true to his roots, has set up his own production base (Wingnut Films) in his home town of Wellington. "I choose to stay in New Zealand earning a fraction of what I could make in Los Angeles because I want to do whatever I feel like doing. . . . The freedom that I have in New Zealand is worth millions of dollars to me." So far, the tactic has worked. By 2000 Jackson was working on his huge, three-part adaptation of Lord of the Rings , with a possible remake of King Kong next in line—all in his native country. The $260 million budget for the Tolkien trilogy is a far cry from the small change it cost to make Bad Taste. But the spirit isn't perhaps so different: armor for the 15,000 extras is being knitted out of string—by the septuagenarian ladies of the Wellington Knitting Club.

—Philip Kemp

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: