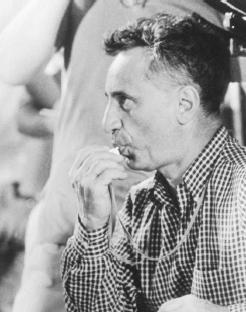

Elia Kazan - Director

Nationality: American. Born: Elia Kazanjoglou in Constantinople (now Istanbul), Turkey, 7 September 1909; moved with family to New York, 1913. Education: Mayfair School; New Rochelle High School, New York; Williams College, Massachusetts, B.A. 1930;

Films as Director:

- 1937

-

The People of the Cumberlands (+ sc) (short)

- 1941

-

It's up to You

- 1945

-

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

- 1947

-

The Sea of Grass ; Boomerang ; Gentleman's Agreement

- 1949

-

Pinky

- 1950

-

Panic in the Streets

- 1952

-

A Streetcar Named Desire ; Viva Zapata! ; Man on a Tightrope

- 1954

-

On the Waterfront

- 1955

-

East of Eden (+ pr)

- 1956

-

Baby Doll (+ pr, co-sc)

- 1957

-

A Face in the Crowd (+ pr)

- 1960

-

Wild River (+ pr)

- 1961

-

Splendour in the Grass (+ pr)

- 1964

-

America, America (+ sc, pr)

- 1969

-

The Arrangement (+ pr, sc)

- 1972

-

The Visitors

- 1976

-

The Last Tycoon

- 1978

-

Acts of Love (+ pr)

- 1982

-

The Anatolian (+ pr)

- 1989

-

Beyond the Aegean

Other Films:

- 1934

-

Pie in the Sky (Steiner) (short) (role)

- 1940

-

City for Conquest (Litvak) (role as Googie, a gangster)

- 1941

-

Blues in the Night (Litvak) (role as a clarinetist)

- 1951

-

The Screen Director (role as himself)

- 1984

-

Sanford Meisner: The American Theatre's Best Kept Secret (Doob) (role as a himself)

- 1989

-

L' Héritage de la chouette ( The Owl's Legacy ) (Marker) (role)

- 1998

-

Liv till varje pris (Jarl) (role as himself)

Publications

By KAZAN: books—

America America , New York, 1961.

The Arrangement , New York, 1967.

The Assassins , New York, 1972.

The Understudy , New York, 1974.

Acts of Love , New York, 1978.

Anatolian , New York, 1982.

Elia Kazan: A Life , New York and London, 1988.

Beyond the Aegean , New York, 1994.

Elia Kazan: A Life , New York, 1997.

Kazan The Master Director Discusses His Films: Interviews with Elia Kazan , edited by Jeff Young, New York, 1999.

By KAZAN: articles—

"The Writer and Motion Pictures," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1957.

Interview with Jean Domarchi and André Labarthe, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), April 1962.

Article in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), December 1963/January 1964.

Interview with S. Byron and M. Rubin, in Movie (London), Win-ter 1971/72.

Interview with G. O'Brien, in Inter/View (New York), March 1972.

"Visiting Kazan," interview with C. Silver and J. Zukor, in Film Comment (New York), Summer 1972.

"All You Need to Know, Kids," in Action (Los Angeles), January/February 1974.

"Hollywood under Water," interview with C. Silver and M. Corliss, in Film Comment (New York), January/February 1977.

"Kazan Issue" of Positif (Paris), April 1977.

"Visite à Yilmaz Güney ou vue d'une prison turque," with O. Adanir, in Positif (Paris), February 1980.

"L'Homme tremblant: Conversation entre Marguerite Duras et Elia Kazan," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), December 1980.

Interview with Tim Pulleine, in Stills (London), July/August 1983.

Interview with P. Le Guay, in Cinématographe (Paris), Febru-ary 1986.

Interview in Time Out (London), 4 May 1988.

"Les américains à trait d'union," in Positif (Paris), June 1994.

"What a Director Needs to Know," in DGA Magazine (Los Ange-les), May-June 1996.

On KAZAN: books—

Clurman, Harold, The Fervent Years: The Story of the Group Theatre and the Thirties , New York, 1946.

Tailleur, Roger, Elia Kazan , revised edition, Paris, 1971.

Ciment, Michel, Kazan on Kazan , London, 1972.

Giannetti, Louis, Masters of the American Cinema , Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1981.

Pauly, Thomas H., An American Odyssey: Elia Kazan and American Culture , Philadelphia, 1983.

Michaels, Lloyd, Elia Kazan: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1985.

Ciment, Michael, An American Odyssey: Elia Kazan , London, 1989.

Murphy, Brenda, Tennessee Williams and Elia Kazan: A Collaboration in the Theatre , Cambridge, 1992.

On KAZAN: articles—

Stevens, Virginia, "Elia Kazan: Actor and Director of Stage and Screen," in Theatre Arts (New York), December 1947.

Archer, Eugene, "Elia Kazan: The Genesis of a Style," in Film Culture (New York), vol. 2, no. 2, 1956.

Archer, Eugene, "The Theatre Goes to Hollywood," in Films and Filming (London), January 1957.

Neal, Patricia, "What Kazan Did for Me," in Films and Filming (London), October 1957.

Bean, Robin, "The Life and Times of Elia Kazan," in Films and Filming (London), May 1964.

Tailleur, Roger, "Elia Kazan and the House Un-American Activities Committee," in Film Comment (New York), Fall 1966.

"Kazan Issue" of Movie (London), Spring 1972.

Changas, E., "Elia Kazan's America," in Film Comment (New York), Summer 1972.

Kitses, Jim, "Elia Kazan: A Structural Analysis," in Cinema (Bev-erly Hills), Winter 1972/73.

Biskind, P., "The Politics of Power in On the Waterfront ," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Autumn 1975.

" A l'est d'Eden Issue" of Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), Novem-ber 1975.

Kazan Section of Positif (Paris), April 1981.

"Kazan Issue" of Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), 1 July 1983.

"Elia Kazan," in Film Dope (London), March 1984.

Michaels, Lloyd, "Elia Kazan: A Retrospective," in Film Criticism (Edinboro, Pennsylvania), Fall 1985.

Neve, Brian, "The Immigrant Experience on Film: Kazan's America America ," in Film and History (New York), vol. 17, no. 3, 1987.

Nangle, J., "The American Museum of the Moving Image Salutes Elia Kazan," in Films in Review (New York), April 1987.

Georgakas, Dan, "Don't Call Him Gadget: Elia Kazan Reconsidered," in Cineaste (New York), vol. 16, no. 4, 1988.

Rathgeb, Douglas, "Kazan as Auteur: The Undiscovered East of Eden ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 16, no. 1, 1988.

McGilligan, Patrick, "Scoundrel Tome," in Film Comment (New York), May/June 1988.

Butler, T., "Polonsky and Kazan. HUAC and the Violation of Personality," in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1988.

Coursodon, Jean-Pierre, in Positif (Paris), October 1989.

Cahir, Linda Costanzo, "The Artful Rerouting of A Streetcar Named Desire ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), April 1994.

White, J., "Sympathy for the Devil: Elia Kazan Looks at the Dark Side of Technological Progress in Wild River ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), October 1994.

Film-Dienst (Cologne), 19 December 1995.

Everschor, Franz, "Arrangement mit dem Schicksal," in Film-Dienst (Cologne), 16 January 1996.

Chase, Donald, "Watershed: Elia Kazan's Wild River ," in Film Comment (New York), November-December 1996.

Benedetto, Robert, " A Streetcar Named Desire : Adapting the Play to the Film," in Creative Screenwriting (Washington, D.C.), Win-ter 1997.

Koehler, Robert, "One from the Heart," in Variety (New York), 1 March 1999.

* * *

Elia Kazan's career has spanned more than four decades of enormous change in the American film industry. Often he has been a catalyst for these changes. He became a director in Hollywood at a time when studios were interested in producing the kind of serious, mature, and socially conscious stories Kazan had been putting on the stage since his Group Theatre days. During the late 1940s and mid-1950s, initially under the influence of Italian neorealism and then the pressure of American television, he was a leading force in developing the aesthetic possibilities of location shooting ( Boomerang, Panic in the Streets, On the Waterfront ) and CinemaScope ( East of Eden, Wild River ). At the height of his success, Kazan formed his own production unit and moved back east to become a pioneer in the new era of independent, "personal" filmmaking that emerged during the 1960s and contributed to revolutionary upheavals within the old Hollywood system. As an archetypal auteur , he progressed from working on routine assignments to developing more personal themes, producing his own pictures, and ultimately directing his own scripts. At his peak during a period (1950–1965) of anxiety, gimmickry, and entropy in Hollywood, Kazan remained among the few American directors who continued to believe in the cinema as a medium for artistic expression and who brought forth films that consistently reflected his own creative vision.

Despite these achievements and his considerable influence on a younger generation of New York-based filmmakers, including Sidney Lumet, John Cassavetes, Arthur Penn, Martin Scorsese, and even Woody Allen, Kazan's critical reputation in America has ebbed. The turning point both for Kazan's own work and the critics' reception of it was almost certainly his decision to become a friendly witness before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1952. While "naming names" cost Kazan the respect of many liberal friends and colleagues (Arthur Miller most prominent among them), it ironically ushered in the decade of his most inspired filmmaking. If Abraham Polonsky, himself blacklisted during the 1950s, is right in claiming that Kazan's post-HUAC movies have been "marked by bad conscience," perhaps he overlooks how that very quality of uncertainty may be what makes films like On the Waterfront, East of Eden , and America America so much more compelling than Kazan's previous studio work.

His apprenticeship in the Group Theater and his great success as a Broadway director had a natural influence on Kazan's films, particularly reflected in his respect for the written script, his careful blocking of scenes, and, pre-eminently, his employment of Method Acting on the screen. While with the Group, which he has described as "the best thing professionally that ever happened to me," Kazan acquired from its leaders, Harold Clurman and Lee Strasberg, a fundamentally artistic attitude toward his work. Studying Marx led him to see art as an instrument of social change, and from Stanislavski he learned to seek a play's "spine" and emphasize the characters' psychological motivation. Although he developed a lyrical quality that informs many later films, Kazan generally employs the social realist mode he learned from the Group. Thus, he prefers location shooting over studio sets, relatively unfamiliar actors over stars, long shots and long takes over editing, and naturalistic forms over genre conventions. On the Waterfront and Wild River , though radically different in style, both reflect the Group's quest, in Kazan's words, "to get poetry out of the common things of life." And while one may debate the ultimate ideology of Gentleman's Agreement, Pinky, Viva Zapata! and The Visitors , one may still agree with the premise they all share, that art should illuminate society's problems and the possibility of their solution.

Above all else, however, it is Kazan's skill in directing actors that has secured his place in the history of American cinema. Twenty-one of his performers have been nominated for Academy Awards; nine have won. He was instrumental in launching the film careers of Marlon Brando, Julie Harris, James Dean, Carroll Baker, Warren Beatty, and Lee Remick. Moreover, he elicited from such undervalued Hollywood players as Dorothy McGuire, James Dunn, Eva Marie Saint, and Natalie Wood perhaps the best performances of their careers. For all the long decline in critical appreciation, Kazan's reputation among actors has hardly wavered. The Method, which became so identified with Kazan's and Lee Strasberg's teaching at the Actors Studio, was once simplistically defined by Kazan himself as "turning psychology into behavior." An obvious example from Boomerang would be the suspect Waldron's gesture of covering his mouth whenever he lies to the authorities. But when Terry first chats with Edie in the park in On the Waterfront , unconsciously putting on one of the white gloves she has dropped as he sits in a swing, such behavior becomes not merely psychological but symbolic and poetic. Here Method acting transcends Kazan's own mundane definition.

His films have been most consistently concerned with the theme of power, expressed as either the restless yearning of the alienated or the uneasy arrangements of the strong. The struggle for power is generally manifested through wealth, sexuality, or, most often, violence. Perhaps because every Kazan film except A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and The Last Tycoon (excluding a one-punch knockout of the drunken protagonist) contains at least one violent scene, some critics have complained about the director's "horrid vulgarity" (Lindsay Anderson) and "unremitting stridency" (Robin Wood), yet even his most "overheated" work contains striking examples of restrained yet resonant interludes: the rooftop scenes of Terry and his pigeons in On the Waterfront , the tentative reunion of Bud and Deanie at the end of Splendor in the Grass , the sequence in which Stavros tells his betrothed not to trust him in America America. Each of these scenes could be regarded not simply as a necessary lull in the drama, but as a privileged, lyrical moment in which the ambivalence underlying Kazan's attitude toward his most pervasive themes seems to crystallize. Only then can one fully realize how Terry in the rooftop scene is both confined by the mise-en-scène (seen within the pigeon coop) and free on the roof to be himself; how Bud and Deanie are simultaneously reconciled and estranged; how Stavros becomes honest only when he confesses to how deeply he has been compromised.

—Lloyd Michaels

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: