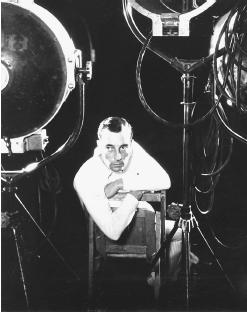

Buster Keaton - Director

Nationality: American. Born: Joseph Francis Keaton in Piqua, Kansas, 4 October 1895. Military Service: Served in U.S. Army, France, 1918. Family: Married 1) Natalie Talmadge, 1921 (divorced 1932), two sons; 2) Mae Scribbens, 1933 (divorced 1935); 3) Eleanor

Norris, 1940. Career: Part of parents' vaudeville act, The Three Keatons, from 1898; when family act broke up, became actor for Comique Film Corp., moved to California, 1917; appeared in 15 tworeelers for Comique, 1917–19; offered own production company with Metro Pictures by Joseph Schenk, 1919, produced 19 two-reelers, 1920–23; directed ten features, 1923–28; dissolved production company, signed to MGM, 1928; announced retirement from the screen, 1933; starred in 16 comedies for Educational Pictures, 1934–39; worked intermittently as gag writer for MGM, 1937–50; appeared in 10 two-reelers for Columbia, 1939–41; appeared on TV and in commercials, from 1949; Cinémathèque Française Keaton retrospective, 1962. Died: Of lung cancer, in Woodland Hills, California, 1 February 1966.

Films as Director and Actor:

- 1920

-

One Week (co-d, co-sc with Eddie Cline); Convict Thirteen (co-d, co-sc with Cline); The Scarecrow (co-d, co-sc with Cline)

- 1921

-

Neighbors (co-d, co-sc with Cline); The Haunted House (co-d, co-sc with Cline); Hard Luck (co-d, co-sc with Cline) The High Sign (co-d, co-sc with Cline); The Goat (co-d, co-sc with Mal St. Clair); The Playhouse (co-d, co-sc with Cline); The Boat (co-d, co-sc with Cline)

- 1922

-

The Paleface (co-d, co-sc with Cline); Cops (co-d, co-sc with Cline); My Wife's Relations (co-d, co-sc with Cline); The Blacksmith (co-d, co-sc with Mal St. Clair); The Frozen North (co-d, co-sc with Cline); Day Dreams (co-d, co-sc with Cline); The Electric House (co-d, co-sc with Cline)

- 1923

-

The Balloonatic (co-d, co-sc with Cline); The Love Nest (co-d, co-sc with Cline); The Three Ages ; Our Hospitality (co-d)

- 1924

-

Sherlock Jr. (co-d); The Navigator (co-d)

- 1925

-

Seven Chances ; Go West (+ story)

- 1926

-

Battling Butler ; The General (co-d, co-sc)

- 1927

-

College (no d credit)

- 1928

-

Steamboat Bill Jr. (no d credit); The Cameraman (no d credit, pr)

- 1929

-

Spite Marriage (no d credit)

- 1938

-

Life in Sometown, U.S.A. ; Hollywood Handicap ; Streamlined Swing

Other Films:

- 1917

-

The Butcher Boy (Fatty Arbuckle comedy) (role as village pest); A Reckless Romeo (Arbuckle) (role as a rival); The Rough House (Arbuckle) (role); His Wedding Night (Arbuckle) (role); Oh, Doctor! (Arbuckle) (role); Fatty at Coney Island (Coney Island) (Arbuckle) (role as husband touring Coney Island with his wife); A Country Hero (Arbuckle) (role)

- 1918

-

Out West (Arbuckle) (role as a dude gambler); The Bell Boy (Arbuckle) (role as a village pest); Moonshine (Arbuckle) (role as an assistant revenue agent); Good Night, Nurse! (Arbuckle) (role as the doctor and a visitor); The Cook (Arbuckle) (role as the waiter and helper)

- 1919

-

Back Stage (Arbuckle) (role as a stagehand); The Hayseed (Arbuckle) (role as a helper)

- 1920

-

The Garage (Arbuckle) (role as a garage mechanic); The Round Up (role as an Indian); The Saphead (role as Bertie "the Lamb" Van Alstyne)

- 1922

-

Screen Snapshots, No. 3 (role)

- 1929

-

The Hollywood Revue (role as an Oriental dancer)

- 1930

-

Free & Easy ( Easy Go ) (role as Elmer Butts); Doughboys (pr, role as Elmer Stuyvesant)

- 1931

-

Parlor, Bedroom & Bath (pr, role as Reginald Irving); Sidewalks of New York (pr, role as Tine Harmon)

- 1932

-

The Passionate Plumber (pr, role as Elmer Tuttle); Speak Easily (role as Professor Timoleon Zanders Post)

- 1933

-

What! No Beer! (role as Elmer J. Butts)

- 1934

-

The Gold Ghost (role as Wally); Allez Oop (role as Elmer); Le Roi des Champs Elysees (role as Buster Garnier and Jim le Balafre)

- 1935

-

The Invader ( The Intruder ) (role as Leander Proudfoot); Palookah from Paducah (role as Jim); One-Run Elmer (role as Elmer); Hayseed Romance (role as Elmer); Tars & Stripes (role as Elmer); The E-Flat Man (role as Elmer); The Timid Young Man (role as Elmer)

- 1936

-

Three on a Limb (role as Elmer); Grand Slam Opera (role as Elmer); La Fiesta de Santa Barbara (role as one of several stars); Blue Blazes (role as Elmer); The Chemist (role as Elmer); Mixed Magic (role as Elmer)

- 1937

-

Jail Bait (role as Elmer); Ditto (role as Elmer); Love Nest on Wheels (last apearance as Elmer)

- 1939

-

The Jones Family in Hollywood (co-sc): The Jones Family in Quick Millions (co-sc); Pest from the West (role as a traveler in Mexico); Mooching through Georgia (role as a Civil War veteran); Hollywood Cavalcade (role)

- 1940

-

Nothing but Pleasure (role as a vacationer); Pardon My Berth Marks (role as a reporter); The Taming of the Snood (role as an innocent accomplice); The Spook Speaks (role as a magician's housekeeper); The Villain Still Pursued Her (role); Li'l Abner (role as Lonesome Polecat); His Ex Marks the Spot (role)

- 1941

-

So You Won't Squawk (role); She's Oil Mine (role); General Nuisance (role)

- 1943

-

Forever and a Day (role as a plumber)

- 1944

-

San Diego, I Love You (role as a bus driver)

- 1945

-

That's the Spirit (role as L.M.); That Night with You (role)

- 1946

-

God's Country (role); El Moderno Barba azul (role as a prisoner of Mexicans who is sent to moon)

- 1949

-

The Loveable Cheat (role as a suitor); In the Good Old Summertime (role as Hickey); You're My Everything (role as butler)

- 1950

-

Un Duel a mort (role as a comic duellist); Sunset Boulevard (Wilder) (role as a bridge player)

- 1952

-

Limelight (Chaplin) (role as the piano accompanist in a music hall sketch); L'incantevole nemica (role in a brief sketch); Paradise for Buster (role)

- 1955

-

The Misadventures of Buster Keaton (role)

- 1956

-

Around the World in Eighty Days (role as a train conductor)

- 1960

-

When Comedy Was King (role in a clip from Cops ); The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Curtiz) (role as a lion tamer)

- 1963

-

Thirty Years of Fun (appearance in clips); The Triumph of Lester Snapwell (role as Lester); It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (Kramer) (role as Jimmy the Crook)

- 1964

-

Pajama Party (role as an Indian chief)

- 1965

-

Beach Blanket Bingo (role as a would-be surfer); Film (role as Object/Eye); How to Stuff a Wild Bikini (role as Bwana); Sergeant Deadhead (Taurog) (role as Private Blinken); The Rail-rodder (role); Buster Keaton Rides Again (role)

- 1966

-

The Scribe (role); A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (Lester) (role as Erronius)

- 1967

-

Due Marines e un Generale ( War, Italian Style ) (role as the German general)

- 1970

-

The Great Stone Face (role)

Publications

By KEATON: book—

My Wonderful World of Slapstick , with Charles Samuels, New York, 1960; revised edition, 1982.

By KEATON: articles—

"Why I Never Smile," in The Ladies Home Journal (New York), June 1926.

Interview with Christopher Bishop, in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Fall 1958.

Interview with Herbert Feinstein, in Massachusetts Review (Am-herst), Winter 1963.

Interview with Kevin Brownlow, in Film (London), no. 42, 1965.

"Keaton: Still Making the Scene," interview with Rex Reed, in New York Times , 17 October 1965.

"Keaton at Venice," interview with John Gillett and James Blue, in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1965.

Interview with Arthur Friedman, in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Summer 1966.

Interview with Christopher Bishop, in Interviews with Film Directors , edited by Andrew Sarris, New York, 1967.

"'Anything Can Happen—And Generally Did': Buster Keaton on His Silent Film Career," interview with George Pratt, in Image (Rochester), December 1974.

Articles from the 1920s reprinted in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), January 1979.

On KEATON: books—

Pantieri, José, L'Originalissimo Buster Keaton , Milan, 1963.

Turconi, Davide, and Francesco Savio, Buster Keaton , Venice, 1963.

Coursodon, Jean-Pierre, Keaton et Compagnie: Les Burlesques américaines du 'muet, ' Paris, 1964.

Oms, Marcel, Buster Keaton , Premier Plan No. 31, Lyons, 1964.

Blesh, Rudi, Keaton , New York, 1966.

Lebel, Jean-Pierre, Buster Keaton , New York, 1967.

Brownlow, Kevin, The Parade's Gone By , New York, 1968.

McCaffrey, Donald, Four Great Comedians , New York, 1968.

Robinson, David, Buster Keaton , London, 1968.

Denis, Michel, "Buster Keaton," in Anthologie du Cinéma , vol. 7, Paris, 1971.

Coursodon, Jean-Pierre, Buster Keaton , Paris, 1973.

Kerr, Walter, The Silent Clowns , New York, 1975.

Anobile, Richard, editor, The Best of Buster , New York, 1976.

Wead, George, Buster Keaton and the Dynamics of Visual Wit , New York, 1976.

Moews, Daniel, Keaton: The Silent Features Close Up , Berkeley, California, 1977.

Wead, George, and George Ellis, The Film Career of Buster Keaton , Boston, 1977.

Dardis, Tom, Keaton: The Man Who Wouldn't Lie Down , New York, 1979.

Benayoun, Robert, The Look of Buster Keaton , Paris, 1982; Lon-don, 1984.

Coursodon, Jean-Pierre, Buster Keaton , Paris, 1986.

Kline, Jim, The Complete Films of Buster Keaton , Secaucus, New Jersey, 1993.

Rapf, Joanna E., and Gary L. Green, Buster Keaton: A Bio-Bibliography , Westport, Connecticut, 1995.

Edwards, Larry, Buster: A Legend in Laughter , Bradenton, Flor-ida, 1995.

Meade, Marion, Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase , New York, 1995.

Oldham, Gabriella, Keaton's Silent Shorts , Carbondale, Illinois, 1996.

Horton, Andrew, editor, Buster Keaton's "Sherlock Jr.," Cambridge and New York, 1997.

On KEATON: articles—

Brand, Harry, "They Told Buster to Stick to It," in Motion Picture Classic (New York), June 1926.

Keaton, Joe, "The Cyclone Baby," in Photoplay (New York), May 1927.

Saalschutz, L., "Comedy," in Close Up (London), April 1930.

Agee, James, "Great Stone Face," in Life (New York), 5 Septem-ber 1949.

Kerr, Walter, "Last Call for a Clown," in Pieces at Eight , New York, 1957.

Agee, James, "Comedy's Greatest Era," in Agee on Film , New York, 1958.

Dyer, Peter, "Cops, Custard—and Keaton," in Films and Filming (London), August 1958.

"Keaton Issue" of Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), August 1958.

Bishop, Christopher, "The Great Stone Face," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Fall 1958.

Baxter, Brian, "Buster Keaton," in Film (London), November/December 1958.

Robinson, David, "Rediscovery: Buster," in Sight and Sound (Lon-don), Winter 1959.

Beylie, Claude, and others, "Rétrospective Buster Keaton," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), April 1962.

Buñuel, Luis, " Battling Butler [ College ]," in Luis Buñuel: An Introduction , edited by Ado Kyrou, New York, 1963.

Lorca, Federico García, "Buster Keaton Takes a Walk," in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1965.

Crowther, Bosley, "Dignity in Deadpan," in The New York Times , 2 February 1966.

Sadoul, Georges, "Le Génie de Buster Keaton," in Les Lettres Françaises (Paris), 10 February 1966.

Benayoun, Robert, "Le Colosse de silence," and "Le Regard de Buster Keaton," in Positif (Paris), Summer 1966.

McCaffrey, Donald, "The Mutual Approval of Keaton and Lloyd," in Cinema Journal (Evanston), no. 6, 1967.

Rhode, Eric, "Buster Keaton," in Encounter (London), Decem-ber 1967.

Houston, Penelope, "The Great Blank Page," in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1968.

Villelaur, Anne, "Buster Keaton," in Dossiers du Cinéma: Cinéastes I , Paris, 1971.

Maltin, Leonard, "Buster Keaton," in The Great Movie Shorts , New York, 1972.

Gilliatt, Penelope, "Buster Keaton," in Unholy Fools , New York, 1973.

Mast, Gerald, "Keaton," in The Comic Mind , New York, 1973.

Sarris, Andrew, "Buster Keaton," in The Primal Screen , New York, 1973.

"Keaton Issue" of Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), February 1975.

Cott, Jeremy, "The Limits of Silent Film Comedy," in Literature/ Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), Spring 1975.

Rubinstein, E., "Observations on Keaton's Steamboat Bill Jr. ," in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1975.

"Special Issue," Castoro Cinema (Firenze), no. 28, 1976.

Everson, William, "Rediscovery: Le Roi des Champs Elysees ," in Films in Review (New York), December 1976.

Wade, G., "The Great Locomotive Chase," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), July/August 1977.

Valot, J., "Discours sur le cinéma dans quelques films de Buster Keaton," in Image et Son (Paris), February 1980.

Gifford, Denis, "Flavour of the Month," in Films and Filming (London), February 1984.

"Buster Keaton," in Film Dope (London), March 1984.

Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1985.

Cazals, T., "Un Monde à la démesure de l'homme," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), March 1987.

Sweeney, K.W., "The Dream of Disruption: Melodrama and Gag Structure in Keaton's Sherlock Junior ," in Wide Angle (Balti-more), vol. 13, no. 1, January 1991.

Sanders, J., and D. Lieberfeld, "Dreaming in Pictures: The Childhood Origins of Buster Keaton's Creativity," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), vol. 47, no. 4, Summer 1994.

Gebert, Michael, "The Art of Buster Keaton," in Video Watchdog (Cincinnati), no. 20, 1995.

Gunning, Tom, "Buster Keaton, or the Work of Comedy in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," in Cineaste (New York), vol. 21, no. 3, 1995.

Tibbetts, John C., "The Whole Show: The Restored Films of Buster Keaton," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 23, no. 4, October 1995.

* * *

Buster Keaton is the only creator-star of American silent comedies who equals Chaplin as one of the artistic giants of the cinema. He is perhaps the only silent clown whose reputation is far higher today than it was in the 1920s, when he made his greatest films. Like Chaplin, Keaton came from a theatrical family and served his apprenticeship on stage in the family's vaudeville act. Unlike Chaplin, however, Keaton's childhood and family life were less troubled, more serene, lacking the darkness of Chaplin's youth that would lead to the later darkness of his films. Keaton's films were more blithely athletic and optimistic, more committed to audacious physical stunts and cinema tricks, far less interested in exploring moral paradoxes and emotional resonances. Keaton's most famous comic trademark, his "great stone face," itself reflects the commitment to a comedy of the surface, but attached to that face was one of the most resiliently able and acrobatic bodies in the history of cinema. Keaton's comedy was based on the conflict between that imperviously dead-pan face, his tiny but almost superhuman physical instrument, and the immensity of the physical universe that surrounded them.

After an apprenticeship in the late 1910s making two-reel comedies that starred his friend Fatty Arbuckle, and after service in France in 1918, Keaton starred in a series of his own two-reel comedies beginning in 1920. Those films displayed Keaton's comic and visual inventiveness: the delight in bizarrely complicated mechanical gadgets ( The Scarecrow, The Haunted House ); the realization that the cinema itself was an intriguing mechanical toy (his use of split-screen in The Playhouse of 1921 allows Buster to play all members of the orchestra and audience, as well as all nine members of a minstrel troupe); the games with framing and composition ( The Balloonatic is a comic disquisition on the surprises one can generate merely by entering, falling out of, or suppressing information in the frame); the breathtaking physical stunts and chases ( Daydreams, Cops ); and the underlying fatalism when his exuberant efforts produce ultimately disastrous results ( Cops, One Week, The Boat ).

In 1923 Keaton's producer, Joseph M. Schenck, decided to launch the comic star in a series of feature films, to replace a previously slated series of features starring Schenck's other comic star, the now scandal-ruined Fatty Arbuckle. Between 1923 and 1929, Keaton made an even dozen feature films on a regular schedule of two a year—always leaving Keaton free in the early autumn to travel east for the World Series. This regular pattern of Keaton's work—as opposed to Chaplin's lengthy laboring and devoted concentration on each individual project—reveals the way Keaton saw his film work. He was not making artistic masterpieces but knocking out everyday entertainment, like the vaudevillian playing the two-a-day. Despite the casualness of this regular routine (which would be echoed decades later by Woody Allen's regular one-a-year rhythm), many of those dozen silent features are comic masterpieces, ranking alongside the best of Chaplin's comic work.

Most of those films begin with a parodic premise—the desire to parody some serious and familiar form of stage or screen melodrama, such as the Civil War romance ( The General ), the mountain feud ( Our Hospitality ), the Sherlock Holmes detective story ( Sherlock Jr. ), the Mississippi riverboat race ( Steamboat Bill Jr. ), or the western ( Go West ). Two of the features were built around athletics (boxing in Battling Butler and every sport but football in College ), and one was built around the business of motion picture photography itself ( The Cameraman ). The narrative lines of these films were thin but fast-paced, usually based on the Keaton character's desire to satisfy the demands of his highly conventional lady love. The film's narrative primarily served to allow the film to build to its extended comic sequences, which, in Keaton's films, continue to amaze with their cinematic ingenuity, their dazzling physical stunts, and their hypnotic visual rhythms. Those sequences usually forced the tiny but dexterous Keaton into combat with immense and elemental antagonists—a rockslide in Seven Chances ; an entire ocean liner in The Navigator ; a herd of cattle in Go West ; a waterfall in Our Hospitality. Perhaps the cleverest and most astonishing of his elemental foes appears in Sherlock Jr. when the enemy becomes cinema itself—or, rather, cinematic time and space. Buster, a dreaming movie projectionist, becomes imprisoned in the film he is projecting, subject to its inexplicable laws of montage, of shifting spaces and times, as opposed to the expected continuity of space and time in the natural universe. Perhaps Keaton's most satisfyingly whole film is The General , virtually an extended chase from start to finish, as the Keaton character chases north, in pursuit of his stolen locomotive, then races back south with it, fleeing his Union pursuers. The film combines comic narrative, the rhythms of the chase, Keaton's physical stunts, and his fondness for mechanical gadgets into what may be the greatest comic epic of the cinema.

Unlike Chaplin, Keaton's stardom and comic brilliance did not survive Hollywood's conversion to synchronized sound. It was not simply a case of a voice's failing to suit the demands of both physical comedy and the microphone. Keaton's personal life was in shreds, after a bitter divorce from Natalie Talmadge. Always a heavy social drinker, Keaton's drinking increased in direct proportion to his personal troubles. Neither a comic spirit nor an acrobatic physical instrument could survive so much alcoholic abuse. In addition, Keaton's contract had been sold by Joseph Schenck to MGM (conveniently controlled by his brother, Nicholas Schenck, head of Loew's Inc., MGM's parent company). Between 1929 and 1933, MGM assigned Keaton to a series of dreary situation comedies—in many of them as Jimmy Durante's co-star and straight man. For the next two decades, Keaton survived on cheap two-reel sound comedies and occasional public appearances, until his major role in Chaplin's Limelight led to a comeback. Keaton remarried, went on the wagon, and made stage, television, and film appearances in featured roles. In 1965 he played the embodiment of existential consciousness in Samuel Beckett's only film work, Film , followed shortly by his final screen appearance in Richard Lester's A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.

—Gerald Mast

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: