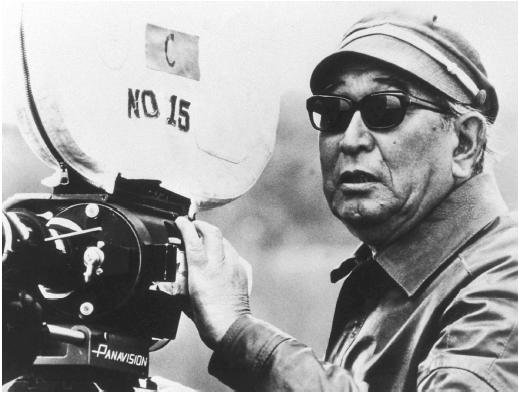

Akira Kurosawa - Director

Nationality: Japanese. Born: Tokyo, 23 March 1910. Education: Kuroda Primary School, Edogawa; Keika High School; studied at Doshusha School of Western Painting, 1927. Family: Married Yoko Yaguchi, 1945 (died, 1985), one son (producer Hisao Kurosawa), one daughter. Career: Painter, illustrator, and member, Japan Proletariat Artists' Group, from late 1920s; assistant director, P.C.L. Studios (Photo-Chemical Laboratory, later Toho Motion Picture Co.), studying in Kajiro Yamamoto's production group, from 1936; also scriptwriter, from late 1930s; directed first film, Sugata Sanshiro , 1943; began association with actor Toshiro Mifune on Yoidore tenshi , and founder, with Yamamoto and others, Motion Picture Artists Association (Eiga Gei jutsuka Kyokai), 1948; formed Kurosawa Productions, 1959; signed contract with producer Joseph E. Levine to work in United States, 1966 (engaged in several aborted projects through 1968); with directors Keisuke Kinoshita, Kon Ichikawa, and Masaki Kobayashi, formed Yonki no Kai production company, 1971. Awards: Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, and Grand Prix, Venice Festival, for Rashomon , 1951; Golden Bear Award for Best Direction and International Critics Prize, Berlin Festival, for The Hidden Fortress , 1959; Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, for Dersu Uzala , 1976; European Film Academy Award, for "humanistic contribution to society in film production," 1978; Best Director, British Academy Award, and Palme d'Or, Cannes Festival, for

Films as Director:

- 1943

-

Sugata Sanshiro ( Sanshiro Sugata, Judo Saga ) (remade as same title by Shigeo Tanaka, 1955, and by Seiichiro Uchikawa, 1965, and edited by Kurosawa) (+ sc)

- 1944

-

Ichiban utsukushiku ( The Most Beautiful ) (+ sc)

- 1945

-

Zoku Sugata Sanshiro ( Sanshiro Sugata—Part 2 ; Judo Saga— II ) (+ sc); Tora no o o fumu otokotachi ( Men Who Tread on the Tiger's Tail ) (+ sc)

- 1946

-

Asu o tsukuru hitobito ( Those Who Make Tomorrow ); Waga seishun ni kuinashi ( No Regrets for Our Youth ) (+ co-sc)

- 1947

-

Subarashiki nichiyobi ( One Wonderful Sunday ) (+ co-sc)

- 1948

-

Yoidore tenshi ( Drunken Angel ) (+ co-sc)

- 1949

-

Shizukanaru ketto ( A Silent Duel ) (+ co-sc); Nora inu ( Stray Dog ) (+ co-sc)

- 1950

-

Shubun ( Scandal ) (+ co-sc); Rashomon (+ co-sc)

- 1951

-

Hakuchi ( The Idiot ) (+ co-sc)

- 1952

-

Ikiru ( To Live, Doomed ) (+ co-sc)

- 1954

-

Shichinin no samurai ( Seven Samurai ) (+ co-sc)

- 1955

-

Ikimono no kiroku ( Record of a Living Being ; I Live in Fear ; What the Birds Knew ) (+ co-sc)

- 1957

-

Kumonosu-jo ( The Throne of Blood ; The Castle of the Spider's Web ) (+ co-sc, co-pr); Donzoko ( The Lower Depths ) (+ co-sc, co-pr)

- 1958

-

Kakushi toride no san-akunin ( The Hidden Fortress ; Three Bad Men in a Hidden Fortress ) (+ co-sc, co-pr)

- 1960

-

Warui yatsu hodo yoku nemuru ( The Worse You Are the Better You Sleep ; The Rose in the Mud ) (+ co-sc, co-pr); Yojimbo ( The Bodyguard ) (+ co-sc)

- 1962

-

Sanjuro (+ co-sc)

- 1963

-

Tengoku to jigoku ( High and Low ; Heaven and Hell ; The Ransom ) (+ co-sc)

- 1965

-

Akahige ( Red Beard ) (+ co-sc)

- 1970

-

Dodesukaden ( Dodeskaden ) (+ co-sc, co-pr)

- 1975

-

Dersu Uzala (+ co-sc)

- 1980

-

Kagemusha ( The Shadow Warrior ) (+ co-sc, co-pr)

- 1985

-

Ran (+ sc)

- 1990

-

Dreams ( Akira Kurosawa's Dreams ) (+ sc)

- 1991

-

Hachigatsu No Kyohshikyoku ( Rhapsody in August ) (+ sc)

- 1993

-

Madadayo (+ sc, ed)

Other Films:

- 1937

-

Sengoku gunto den ( Sage of the Vagabond ) (sc, asst dir)

- 1941

-

Uma ( Horses ) (Yamamoto) (co-sc)

- 1942

-

Seishun no kiryu ( Currents of Youth ) (Fushimizi) (sc); Tsubasa no gaika ( A Triumph of Wings ) (Yamamoto) (sc)

- 1944

-

Dohyo-matsuri ( Wrestling-Ring Festival ) (Marune) (sc)

- 1945

-

Appare Isshin Tasuke ( Bravo, Tasuke Isshin! ) (Saeki) (sc)

- 1947

-

Ginrei no hate ( To the End of the Silver Mountains ) (Taniguchi) (co-sc); Hatsukoi ( First Love ) segment of Yottsu no koi no monogatari ( Four Love Stories ) (Toyoda) (sc)

- 1948

-

Shozo ( The Portrait ) (Kinoshita) (sc)

- 1949

-

Yakoman to Tetsu ( Yakoman and Tetsu ) (Taniguchi) (sc); Jigoku no kifujin ( The Lady from Hell ) (Oda) (sc)

- 1950

-

Akatsuki no dasso ( Escape at Dawn ) (Taniguchi) (sc); Jiruba no Tetsu ( Tetsu 'Jilba' ) (Kosugi) (sc); Tateshi danpei ( Fencing Master ) (Makino) (sc)

- 1951

-

Ai to nikushimi no kanata e ( Beyond Love and Hate ) (Taniguchi) (sc); Kedamono no yado ( The Den of Beasts ) (Osone) (sc); Ketto Kagiya no tsuji ( The Duel at Kagiya Corner ) (Mori) (sc)

- 1957

-

Tekichu odan sanbyakuri ( Three Hundred Miles through Enemy Lines ) (Mori) (sc)

- 1960

-

Sengoku guntoden ( The Saga of the Vagabond ) (Sugie) (sc)

- 1999

-

Ame agaru ( After the Rain ) (co-sc)

Publications

By KUROSAWA: books—

Ikiru , with Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni, edited by Donald Richie, New York, 1968.

Rashomon , with Shinobu Hashimoto, edited by Donald Richie, New York, 1969; also New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1987.

The Seven Samurai , New York, 1970.

Kurosawa Akira eiga taikei [Complete Works of Akira Kurosawa], edited by Takamaro Shimaji, in 12 volumes, Tokyo, 1970/72.

Something like an Autobiography , New York, 1982.

Ran , London, 1986.

By KUROSAWA: articles—

"Waga eiga jinsei no ki," [Diary of My Movie Life], in Kinema jumpo (Tokyo), April 1963.

"Why Mifune's Beard Won't Be Red," in Cinema (Los Angeles), July 1964.

"L'Empereur: entretien avec Kurosawa," with Yoshio Shirai and others, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), September 1966.

Interview with Donald Richie, in Interviews with Film Directors , edited by Andrew Sarris, New York, 1967.

Interview with Joan Mellen, in Voices from the Japanese Cinema , New York, 1975.

"Tokyo Stories: Kurosawa," interview with Tony Rayns, in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1981.

Interview with E. Decaux and B. Villien, in Cinématographe (Paris), April 1982.

"Kurosawa on Kurosawa," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), April 1982.

Interview with Kyoko Hirano, in Cineaste (New York), May 1986.

Kurosawa, Akira, "Lat oss halla ut tillsammaus," in Chaplin (Stock-holm), vol. 30, no. 2/3, 1988.

Interview in Time Out (London), 9 May 1990.

Interview in Etudes Cinematographiques (Paris), no. 165/169, 1990.

Interview in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), June 1991.

"Moments with Kurosawa," an interview with Shawn Levy and James Fee, in American Film (New York), January/February 1992.

On KUROSAWA: books—

Anderson, Joseph, and Donald Richie, The Japanese Film: Art and Industry , New York, 1960; revised edition, Princeton, New Jer-sey, 1982.

Sato, Tadao, Kurosawa Akira no sekai [The World of Akira Kurosawa], Tokyo, 1968.

Richie, Donald, The Films of Akira Kurosawa , Berkeley, California, 1970; revised edition, 1984.

Richie, Donald, Japanese Cinema: Film Style and National Character , New York, 1971.

Richie, Donald, editor, Focus on Rashomon , Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1972.

Mesnil, Michel, Kurosawa , Paris, 1973.

Mellen, Joan, The Waves at Genji's Door: Japan through Its Cinema , New York, 1976.

Bock, Audie, Japanese Film Directors , New York, 1978; revised edition, Tokyo, 1978.

Erens, Patricia, Akira Kurosawa: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1979.

Tassone, Aldo, Akira Kurosawa , Florence, 1981.

Bazin, André, The Cinema of Cruelty: From Buñuel to Hitchcock , New York, 1982.

Sato, Tadao, Currents in Japanese Cinema , Tokyo, 1982.

Desser, David, The Samurai Films of Akira Kurosawa , Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1983.

Tassone, Aldo, Akira Kurosawa , Paris, 1983.

Ito, Kosuke, Kurosawa Akira 'Ran' no sekai , Tokyo, 1985.

Achternbusch, Herbert, and others, Akira Kurosawa , Munich, 1988.

Chang, Kevin K., Kurosawa: Perceptions on Life , Honolulu, Hawaii, 1991.

Prince, Stephen, The Warrior's Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa , Princeton, New Jersey, 1991.

Goodwin, James, editor, Perspectives on Akira Kurosawa , New York, 1994.

On KUROSAWA: articles—

Leyda, Jay, "The Films of Kurosawa," in Sight and Sound (London), October/December 1954.

Anderson, Lindsay, "Two Inches off the Ground," in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1957.

Anderson, Joseph, and Donald Richie, "Traditional Theater and the Film in Japan," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Fall 1958.

McVay, Douglas, "The Rebel in a Kimono," and "Samurai and Small Beer," in Films and Filming (London), July and August 1961.

"Kurosawa Issues" of Kinema jumpo (Tokyo), April 1963 and 5 September 1964.

"Akira Kurosawa," in Cinema (Los Angeles), August/September 1963.

"Kurosawa Issue" of Études Cinématographiques (Paris), no. 30–31, Spring 1964.

Akira, Iwasaki, "Kurosawa and His Work," in Japan Quarterly (New York), January/March 1965.

"Director of the Year," International Film Guide (London, New York), 1966.

"Akira Kurosawa: Japan's Poet Laureate of Film," in Film Makers on Film Making , edited by Harry Geduld, Bloomington, Indi-ana, 1967.

Richie, Donald, "Dostoevsky with a Japanese Camera," in The Emergence of Film Art , edited by Lewis Jacobs, New York, 1969.

Manvell, Roger, "Akira Kurosawa's Macbeth, The Castle of the Spider's Web ," in Shakespeare and the Film , London, 1971.

Tessier, Max, "Cinq japonais en quete de films: Akira Kurosawa," in Ecran (Paris), March 1972.

Mellen, Joan, "The Epic Cinema of Kurosawa," in Take One (Montreal), June 1972.

Kaminsky, Stuart, "The Samurai Film and the Western," in The Journal of Popular Film (Bowling Green, Ohio), Fall 1972.

Tucker, Richard, "Kurosawa and Ichikawa: Feudalist and Individualist," in Japan: Film Image , London, 1973.

"Kurosawa Issue" of Kinema jumpo (Tokyo), 7 May 1974.

Richie, Donald, "Kurosawa: A Television Script," in 1000 Eyes (New York), May 1976.

Silver, Alain, "Akira Kurosawa," in The Samurai Film , Cranbury, New Jersey, 1977.

McCormick, Ruth, "Kurosawa: The Nature of Heroism," in 1000 Eyes (New York), April 1977.

Ray, Satyajit, "Tokyo, Kyoto, et Kurosawa," in Positif (Paris), December 1979.

Mitchell, G., "Kurosawa in Winter," in American Film (Washing-ton, D.C.), April 1982.

Dossier on Ran , in Revue du Cinéma (Paris), September 1985.

"Kurosawa Section" of Positif (Paris), October 1985.

Boyd, D., " Rashomon : from Akutagawa to Kurosawa," in Literature-Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 15, no. 3, 1987.

Kusakabe, K., "Akira Kurosawa, the Emperor of Cinema," in Cinema India International (Bombay), vol. 4, no. 13, 1987.

Lannes-Lacroutz, M., "Le Sabra et la camélia," in Positif (Paris), March 1987.

McCarthy, T., "Kurosawa Mum on Next Film during Audience in Tokyo," in Variety (New York), 7 October 1987.

Prince, S., "Zen and Selfhood: Patterns of Eastern Thought in Kurosawa's Films," in Post Script (Jacksonville, Florida), Winter 1988.

Ostria, V., "Kurosawa en vogue," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), January 1989.

Stein, Elliot, "Film: Foreign Affairs," in Village Voice (New York), 31 January 1989.

Peary, G., "Akira Kurosawa," in American Film (New York), April 1989.

Positif (Paris), June 1990.

Biofilmography in L'avant Scene Cinéma (Paris), June 1990.

Weisman, S.R., "Kurosawa Is Sailing Unfamiliar Seas," New York Times , October 1, 1990.

Bibliography in L'avant Scene Cinéma (Paris), June-July 1991.

Bourguignon, Thomas, article in Positif (Paris), November 1991.

Medine, David, "Law and Kurosawa's 'Rashomon,"' in Literature-Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), January 1992.

Sterngold, James, "Kurosawa, in His Own Style, Is Planning His Next Film," in New York Times , 1 February 1992.

Helm, Leslie, "Is Kurosawa Ready to Stop Making Films? Not Yet . . . ," in Los Angeles Times , 24 June 1992.

Segers, F., "Kurosawa and Toho Go Way Back," in Variety (New York), 9 November 1992.

Seltzer, Alex, "Akira Kurosawa: Seeing through the Eyes of the Audience," in Film Comment (New York), May/June 1993.

Reid, T.R., "The Setting Sun of Akira Kurosawa; Japan's Famed Director Draws Yawns for Film Memoir," in Washington Post , 28 December 1993.

Crowl, Samuel, "The Bow Is Bent and Drawn: Kurosawa's 'Ran' and the Shakespearean Arrow of Desire," in Literature-Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), April 1994.

Manheim, Michael, "The Function of Battle Imagery in Kurosawa's Histories and the 'Henry V' Films," in Literature-Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), April 1994.

James, Caryn, "Gleaning a Master Director's Painted Clues. . . ," in New York Times , 5 June 1994.

Masson, Alain, and others, "Akira Kurosawa," in Positif (Paris), January 1996.

Bovkis, Elen A., " Ikiru : The Role of Women in a Male Narrative," in CineAction (Toronto), May 1996.

Carr, Barbara, "Goethe and Kurosawa: Faust and the Totality of Human Experience—West and East," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), vol. 24, no. 3, 1996.

Obituary, in Filmrutan (Sundsvall), Fall 1998.

Obituary, in Variety (New York), 14 September 1998.

Obituary, in Sight and Sound (London), October 1998.

Obituary, in Positif (Paris), November 1998.

Obituary, in 24 Images (Montreal), no. 95, Winter 1998.

On KUROSAWA: film—

Richie, Donald, Akira Kurosawa: Film Director , 1975.

* * *

Unquestionably Japan's best-known film director, Akira Kurosawa introduced his country's cinema to the world with his 1951 Venice Festival Grand Prize winner, Rashomon. His international reputation has broadened over the years with numerous citations, and when 20th Century-Fox distributed his 1980 Cannes Grand Prize winner, Kagemusha , it was the first time a Japanese film achieved worldwide circulation through a major Hollywood studio.

At the time Rashomon took the world by surprise, Kurosawa was already a well-established director in his own country. He had received his six-year assistant director's training at the Toho Studios under the redoubtable Kajiro Yamamoto, director of both low-budget comedies and vast war epics such as The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya. Yamamoto described Kurosawa as more than fully prepared to direct when he first grasped the megaphone for his own screenplay, Sanshiro Sugata , in 1943. This film, based on a best-selling novel about the founding of judo, launched lead actor Susumu Fujita as a star and director Kurosawa as a powerful new force in the film world.

Despite numerous battles with wartime censors, Kurosawa managed to get production approval for three more of his scripts before the Pacific War ended in 1945. By this time he was fully established with his studio and his audience as a writer-director. His films were so successful commercially that he would, until late in his career, receive a free creative hand from his producers, ever-increasing budgets, and extended schedules. In addition, he was never subjected to a project that was not of his own initiation and his own writing.

In the pro-documentary, female emancipation atmosphere that reigned briefly under the Allied Occupation of Japan, Kurosawa created his strongest woman protagonist and produced his most explicit pro-left message in No Regrets for Our Youth. But internal political struggles at Toho left bitterness and creative disarray in the wake of a series of strikes. As a result, Kurosawa's 1947 One Wonderful Sunday is perhaps his weakest film, an innocuous and sentimental story of a young couple who are too poor to get married.

The mature Kurosawa appeared in the 1948 Drunken Angel. Here he displays not only a full command of black-and-white filmmaking technique with his characteristic variety of pacing, lighting, and camera angles for maximum editorial effect, but his first use of sound-image counterpoints in the "Cuckoo Waltz" scene, where lively music contrasts with the dying gangster's dark mood. Here too is the full-blown appearance of the typical Kurosawan master-disciple relationship first suggested in Sanshiro Sugata , as well as an overriding humanitarian message despite the story's tragic outcome. The master-disciple roles assume great depth in Takashi Shimura's portrayal of the blustery alcoholic doctor and Toshiro Mifune's characterization of the vain, hotheaded young gangster. The film's tension is generated by Shimura's questionable worthiness as a mentor and Mifune's violent unwillingness as a pupil. These two actors would recreate similar testy relationships in numerous Kurosawa films from the late 1940s through the mid-1950s, including the noir police drama Stray Dog , the doctor dilemma film Quiet Duel , and the all-time classic Seven Samurai. In the 1960s Yuzo Kayama would assume the disciple role to Mifune's master in the feudal comedy Sanjuro and in Red Beard , a work about humanity's struggle to modernize.

Kurosawa's films of the 1990s were minor asterisks to the career of this formidable, legendary director. Dreams (Akira Kurosawa's Dreams) is a disappointingly uneven recreation of eight of the director's dreams; Hachigatsu No Kyohshikyoku (Rhapsody in August) is a slight account of the recollection of a grandmother who remembers the bombing of Nagasaki.

These films are linked to Madadayo , Kurosawa's last film, in that all are deeply personal and reflective. Madadayo , released when Kurosawa was 83 years old, is an account of 17 years in the retirement of a beloved teacher who is respected by the generations of his former students. As he ages into a "genuine old man," he remains as feisty and vigorous as ever; his favorite phrase is the film's title, the English translation of which is "not yet." But he is as equally vulnerable to the ravages of time and life's losses, as illustrated by his grieving upon the disappearance of his pet cat. Madadayo is a flawed film, if only because one too many sequences ramble. While it most decidedly is the work of an old man, it and his other latter-period work do not negate the vitality of Kurosawa's many all-time classics.

Part of Kurosawa's characteristic technique throughout his career involved the typical Japanese studio practice of using the same crew or "group" on each production. He consistently worked with cinematographer Asakazu Nakai and composer Fumio Hayasaka, for example. Kurosawa's group became a kind of family that extended to actors as well. Mifune and Shimura were the most prominent names of the virtual private repertory company that, through lifetime studio contracts, could survive protracted months of production on a Kurosawa film and fill in with more normal four-to-eight-week shoots in between. Kurosawa was thus assured of getting the performance he wanted every time.

Kurosawa's own studio contract and consistent box-office record enabled him to exercise creativity never permitted lesser talents in Japan. He was responsible for numerous technical innovations as a result. He pioneered the use of long lenses and multiple cameras in the famous final battle scenes in the driving rain and splashing mud of Seven Samurai. He introduced the first use of widescreen in Japan in the 1958 samurai entertainment classic Hidden Fortress. To the dismay of leftist critics and the delight of audiences, he invented realistic portrayals of swordfighting and other violence in such extravagant confrontations as those of Yojimbo , which spawned the entire Clint Eastwood spaghetti western genre in Italy. Kurosawa further experimented with long lenses on the set in Red Beard , and accomplished breathtaking work with his first color film Dodeskaden , now no longer restorable. A firm believer in the importance of motion picture science, Kurosawa pioneered the use of Panavision and multi-track Dolby sound in Japan with Kagemusha. His only reactionary practice was his editing, which he did entirely himself on an antique Moviola, better and faster than anyone else in the world.

Western critics often chastised Kurosawa for using symphonic music in his films. His reply to this is to point out that he and his entire generation grew up on music that was more Western in quality than native Japanese. As a result, native Japanese music can sound artificially exotic to a contemporary audience. Nevertheless, he succeeded in his films in adapting not only boleros and elements of Beethoven, but snatches of Japanese popular songs and musical instrumentation from Noh theater and folk song.

Perhaps most startling of Kurosawa's achievements in a Japanese context, however, was his innate grasp of a story-telling technique that is not culture bound, and his flair for adapting Western classical literature to the screen. No other Japanese director would have dared to set Dostoevski's Idiot , Gorki's Lower Depths , or Shakespeare's Macbeth (Throne of Blood) and King Lear (Ran) in Japan. But he also adapted works from the Japanese Kabuki theater ( Men Who Tread on the Tiger's Tail ) and used Noh staging techniques and music in both Throne of Blood and Kagemusha. Like his counterparts and most admired models, Jean Renoir, John Ford, and Kenji Mizoguchi, Kurosawa took his cinematic inspirations from the full store of world film, literature, and music. And yet the completely original screenplays of his two greatest films, Ikiru , the story of a bureaucrat dying of cancer who at last finds purpose in life, and Seven Samurai , the saga of seven hungry warriors who pit their wits and lives against marauding bandits in the defense of a poor farming village, reveal that his natural story-telling ability and humanistic convictions transcended all limitations of genre, period, and nationality.

—Audie Bock, updated by Rob Edelman

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: