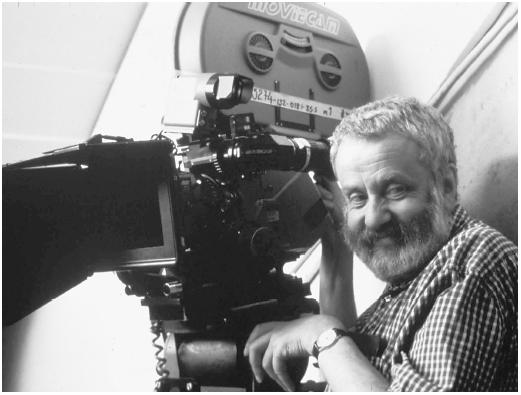

Mike Leigh - Director

Nationality: British. Born: Salford, Lancashire, 20 February 1943. Education: Attended North Grecian Street County Primary School, Salford, and Salford Grammar School; studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, London, 1960–62, Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts, London, 1963–64, Central School of Art and Design, London, 1964–65, and London Film School, 1965. Family: Married actress Alison Steadman, 1973; two sons. Career: Founded, with David Halliwell, the production company Dramagraph, London, 1965; associate director, Midlands Art Centre for Young People, Birmingham, 1965–66; actor, Victoria Theatre, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire,

Films as Director:

(Feature films)

- 1971

-

Bleak Moments

- 1988

-

High Hopes

- 1990

-

Life Is Sweet

- 1993

-

Naked

- 1996

-

Secrets and Lies

- 1997

-

Career Girls

- 1999

-

Topsy-Turvy

(Television films)

- 1972

-

A Mugs Game ; Hard Labour

- 1975

-

The Permissive Society ; group of five 5-minute films: The Birth of the 2001 FA Cup Final Goalie ; Old Chums ; Probation ; A Light Snack ; Afternoon

- 1976

-

Nuts in May ; Plays for Britain (title sequence only); Knock for Knock ; The Kiss of Death

- 1977

-

Abigail's Party

- 1978

-

Who's Who

- 1980

-

Grown-Ups

- 1982

-

Home Sweet Home

- 1983

-

Meantime

- 1985

-

Four Days in July

- 1987

-

The Short and Curlies

- 1992

-

A Sense of History

Publications

By LEIGH: books—

Mike Leigh, Interviews: Interviews (Conversations with Filmmakers) , edited by Howie Movshovitz, Jackson, 2000.

On LEIGH: books—

Clements, Paul, The Improvised Play: The Work of Mike Leigh , London, 1983.

Coveney, Michael, The World according to Mike Leigh , New York, 1996.

Carney, Ray, The Films of Mike Leigh: Embracing the World , New York, 2000.

By LEIGH: articles—

"Bleak Moments," an interview with C. Montvalon, in Image et Son , December 1973.

"Mike Leigh, miniaturiste du social," an interview with Isabelle Ruchti, in Positif (Paris), April 1989.

" Life Is Sweet /A Conversation with Mike Leigh," an interview with Barbara Quart, Leonard Quart, and J. Bloch, in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Spring 1992.

"Mike Leigh. Chaos in der Vorstadt," an interview with Robert Fischer, in EPD Film (Frankfurt), February 1994.

"L'histoire d'un bad boy," an interview with Cécile Mury, in Télérama (Paris), 10 May 1995.

"Gloom with a View," an interview with Steve Grant, in Time Out (London), 22 May 1996.

"A Conversation with Mike Leigh," an interview with S.B. Katz, in Written By. Journal: The Writers Guild of America, West (Los Angeles), October 1996.

"Exposures & Truths," an interview with A. White, in Variety's On Production (Los Angeles), no. 10, 1996.

"Life by Mike Leigh," an interview with S. Johnston, in Interview , November 1996.

" Secrets & Lies/ Raising Questions and Positing Possibilities," an interview with Richard Porton and Leonard Quart, in Cineaste (New York), March 1997.

"How to Direct a DGA-nominated Feature: Jeremy Kagan Interviews Four Who Did," in DGA Magazine (Los Angeles), May-June 1997.

Interview with P. Malone, in Film en Televisie + Video (Brussels), September 1997.

On LEIGH: articles—

Taylor, John Russell, "Giggling beneath the Waves: The Uncosy World of Mike Leigh," in Sight and Sound , Winter 1982/83.

Boyd, William, "Seeing Is Believing," in New Statesman , 17 September 1982.

French, Sean, "Life on the Edge without a Script," in Observer Magazine , 8 January 1989.

Ruchti, Isabelle, "Mike Leigh, miniaturiste du social," in Positif , April 1989.

Kermode, Mark, "Inherently and Inevitably Awful: Mike Leigh," in Monthly Film Bulletin , March 1991.

Cieutat, Michel, "Glauques esperances," in Positif , September 1991.

Kennedy, Harlan, "Mike Leigh about His Stuff," in Film Comment , September/October 1991.

Hoberman, J., "Cassavetes and Leigh: Poets of the Ordinary," in Premiere , October 1991.

Adams, Mark, "A Long Weekend with Mike Leigh," in National Film Theatre Programme , May 1993.

Naked Issue of L'Avant-Scene du Cinéma , November 1993.

Berthin-Scaillet, Agnes, "Lignes de fuite," in Positif , November 1993.

Medhurst, Andy, "Mike Leigh: Beyond Embarrassment," in Sight and Sound , November 1993.

Ellickson, Lee, and Richard Porton, "I Find the Tragicomic Things in Life," in Cineaste , vol. 20, no. 3, 1994.

Smith, Gavin, "Worlds Apart," in Film Comment , September/October 1994.

Paletz, Gabriel M., and David L. Paletz, "Mike Leigh's Naked Truth," in Film Criticism , Winter 1994/95.

Herpe, Noël and O'Neill, Eithne and Ciment, Michel, " Secrets et mensonges ," in Positif (Paris), September 1996.

Kino (Warsaw), February 1998.

* * *

The international success, both critical and popular, of Secrets and Lies in 1996 brought British director Mike Leigh his widest recognition to date and almost drew him into the mainstream. However, this fiercely independent minded, and individualistically creative director chose to continue along the same road he had been traveling for some 25 years. Like his compatriots Ken Loach and Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh had built up a remarkable body of television work years before he became known to a wider international audience with his film High Hopes. As early as 1982 the BBC screened a retrospective of his work, as well as devoting a whole edition of its arts programme Arena to him. By contrast, Americans had to wait another ten years to see what had led up to High Hopes , when the New York Museum of Modern Art staged a retrospective in 1992. In fact, High Hopes was only Leigh's second feature in seventeen years, the first being Bleak Moments , which was largely funded by Albert Finney's company Memorial Enterprises (also behind Stephen Frears's Gumshoe in 1971) at a time when the British cinema had almost ceased to exist—- or, as Leigh puts it, "was alive and well and hiding-out in television, mostly at the BBC."

So, as the critic Sean French wrote in an article on the director in the Observer: "For years Leigh has been making better and more penetrating films than anyone else about the class system ( Nuts in May and Grown-Ups ), unemployment ( Meantime ), Northern Ireland ( Four Days in July ), and family life under Thatcher ( High Hopes ). By almost any reckoning Leigh should be considered one of our major film directors, yet he is virtually ignored in most considerations of British cinema." With the release of Naked this situation improved somewhat, but it is hard to avoid the conclusion that although Leigh is better known in Britain than he was formerly, he remains, like Ken Loach, generally more highly regarded abroad than in his own country.

That Leigh has found it difficult to make feature films is certainly a sad comment on the often sickly state of the British film industry. But as he himself admits, his approach to filmmaking could seem offputting even to the most sympathetic of financiers: "I only accept a project if nobody else wants to know what it's going to be. I come along and say 'I've got no script, I really don't know what I'm going to do, just give me the money and I'll bugger off and do it."' And doing it is time-consuming—the rehearsals for High Hopes took a not untypical fifteen weeks.

It is impossible to discuss Leigh's work without discussing his working methods, even though there's an unfortunate tendency amongst critics to fetishise these to the point of ignoring what the resulting films are actually all about. Leigh himself has referred to such writings as "an albatross, a media preoccupation," but since misunderstandings abound and are often used as a basis on which to attack his work, it is important to understand what he is doing. In fact, his methods have changed little since he developed them in the theatre in the mid-1960s. As he said in 1973: "I begin with a general area which I want to investigate. I choose my actors and tell them that I don't want to talk to them about the play. (There is no play at this stage.) I ask them to think of several people of their own age. Then we discuss these people till we find the character I want." Each actor then builds up his or her own character through a lengthy process of research and improvisation, both in the rehearsal room and in real locations. Only when the actors have fully 'found' their characters are they brought together and the all-important relationships are formed between the characters: the play is what happens to the characters, what they make for themselves. Behaviour dictates situation."

For Leigh there is no great mystique about improvisation; as he described it in 1980: "Improvisation is actually a practical way of investigating real-life going on the way real life actually operates. That's all." At the same time, however, he is utterly opposed to the notion of improvisation as "some kind of all-in anarchic democracy." To quote from the same 1980 interview: "It is a question of discovering what the film or play is about by making the film. It isn't a committee job nor is it 'let's just see what happens and go along with it.' Nor is it a question of shooting a lot of footage in which actors improvise. In my films 98 percent is structured." The main work, therefore, is done in research, improvisation, and rehearsal long before the cameras appear; by that time "there's very much a script. It just so happens that I don't start with a document, that's all. What finally appears on screen is only very, very rarely improvised in front of the camera. For the most part it's arrived at through a long process, and it's finally pinned down and rehearsed and very disciplined, while the quality of the language and the imagery is heightened. . . Improvisation and research are simply tactics, a means to an end and not an end in themselves." It is for these reasons that most of his television films carry the unique credit "devised and directed by Mike Leigh," and the theater critic Benedict Nightingale once described him as "part composer, part conductor, part catalyst." And whatever the critical misunderstandings surrounding Leigh's method, it certainly brings results. His cast lists have included some of Britain's finest younger actors, such as Alison Steadman, Anthony Sher, Jim Broadbent, Gary Oldman, Tim Roth, Lindsay Duncan, David Thewlis, Frances Barber, and Jane Horrocks, many of whom have done some of their best work for him.

Given Leigh's improvisatory methods, it is no surprise to find that films such as On the Waterfront , Rebel without a Cause , and Shadows were early influences. Rather more interesting, however, is his citing of the playwrights Beckett and Pinter and the artists Hogarth, Gilray, and Rowlandson as major inspirations. This points us towards a central fact of Leigh's oeuvre: that it is absolutely not naturalistic, and that critics who have tried to pigeonhole it as such are largely to blame for the tired old saw that Leigh cannot portray "real people" without sneering or laughing at them, or being condescending. Perhaps the best way to describe Leigh's work is as distilled or heightened realism, which certainly does not preclude elements of humour and even caricature in his depiction of character. For example, the frightful yuppies the Booth-Braines in High Hopes and the appalling Jeremy in Naked are certainly caricatures but they are entirely, indeed all too, believable, as is the terrifying Beverly in Abigail's Party. For all the demotic, quotidian surface appearances of his films, Leigh expresses a remarkably consistent and personal view through them. In his work, implicitly, a great deal is suggested about the way life might, or should, be by showing, in a particular way, the world as it actually is. Speaking at the time of the release of High Hopes Leigh talked revealingly of "distilling my metaphor out of an absolutely tangible, real and solid and plausible and vulnerable and unheroic and unexotic kind of world," and not for nothing in that film does he have his most positive characters, Cyril and Shirley, visit the tomb of Karl Marx in Highgate Cemetery, on which is written: "The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways. The point however is to change it." Not that Leigh offers any easy answers—and certainly not Marxist solutions—something else which has hardly endeared him to the Left in Britain. Or as he puts it: "For me the whole experience of making films is one of discovery. What is important, it seems to me, is that you share questions with the audience, and they have to go away with things to work on. That's not a cop out. It is my natural, instinctive way of story-telling and sharing ideas, predicaments, feelings and emotions." On the other hand, as a perceptive article in Cineaste remarked: "Although Leigh resolutely refuses to engage in sloganeering, his films are acutely political since they consistently articulate an often hilarious critique of everyday life. This critique is always rooted in the idiosyncracies of individual characters."

If anything could sum up Leigh's vision it might be Thoreau's famous remark about the mass of people living "lives of quiet desperation," and one is also reminded of Chekov in the way his films seem constantly to hover between comedy and tragedy, with despair lurking never very far beneath the surface. As he himself once remarked, "there's no piece that isn't, somewhere along the way, a lamentation for the awfulness of life." In more specifically English terms other reference points might be Alan Ayckbourn (however much Leigh would disagree), Alan Bennett, and Victoria Wood. Although his films are often taken to be about "Englishness"—or even more specifically, about life under the appalling social experiment commonly known as Thatcherism (although much of Leigh's work actually predates the egregious regime)—their success abroad suggests that they tap into rather more universal doubts and fears about the human condition. This is certainly the case with Naked , which, through Johnny's rantings and ravings about chaos theory, Nostradamus, Revelations, and God knows what else, achieves much more than a particularly rancid glimpse of a squalid corner of this septic isle and exudes an imminent, all-pervasive sense of geopolitical doom.

Yet there is something quintessentially English about Leigh's films, and maybe that is why certain English people do not like them. As the novelist William Boyd observed in a piece on Leigh in the New Statesman , on the occasion of the above-mentioned BBC retrospective: "Any edginess or unease prompted by his observations can only be a sign that certain truths are too uncomfortable for some critics to acknowledge. Ostrich complexes are easily fostered; complacency is a very tolerable frame of mind." And not for nothing did Vincent Canby once describe Leigh as not only "the most innovative of contemporary English filmmakers" but "also the most subversive." Whether it's the cruelly, painfully funny examination of preternatural shyness and sexual ineptitude of Bleak Moments , the suburban Strindberg of Abigail's Party , or the excruciating family row into which High Hopes gradually boils up, the vision of England that emerges, though leavened by absurdity, humour, and moments of human warmth and togetherness, is hardly an attractive one. As Andy Medhurst remarked in one of the better British pieces on Leigh: "This England is specific, palpable and dire, though aspects of it are at the same time liable to inspire a kind of wry resignation. . . . If anything, Englishness is revealed as a kind of pathological condition, emotionally warping and stunting, to which the only response can be a kind of damage limitation. What many of Leigh's films suggest is that to be English is to be locked in a prison where politeness, gaucheness and anxiety about status form the bars across the window. . . . His best films ( Bleak Moments, Grown-Ups, Meantime ) exemplify his skills as a choreographer of awkwardness, a geometrician of embarrassments, able to orchestrate layers of accumulated tiny cruelties and failures of comunication until they swell into a crescendo of extravagant farce."

These elements synthesised into a perfectly orchestrated exposp of racial bigotry and trumped-up suburban pretension in Secrets and Lies which, though profoundly "English" in its locales and modes of spoken expression, cut through cultural barriers to touch a universal nerve. Combining humor with its sly attack on value systems and its overt critique of racist misperceptions, Secrets and Lies offers an unusually (for Leigh) clear redemptive ending to the upheavals caused when a young black woman (Marianne Jean-Baptiste), given up for adoption at birth, seeks out her real mother (Brenda Blethyn) only to discover that she is white. Garlanded with honors, awards, and Oscar nominations, the film made Mike Leigh more bankable than he had ever been and he embarked on his next feature film with unprecedented speed.

However, Career Girls , released to eagerly expectant critics and audiences the following year, seemed to puzzle rather than please, and was not a success. It is difficult to account for this reaction. The film, which cuts back and forth between the present—when two young women who shared a flat in their college years meet up again for a weekend in London—and their shared past, certainly deviates from its maker's previous work in the close focus on the protagonists, each trapped in her own private disillusion, rather than observing a broad canvas of interaction. However, it's beautifully observed, well-played, and very accessible. Perhaps audiences, post- Secrets and Lies , were more interested in at least the promise of a happy ending than in the unmistakably bleak emotional territory occupied by Career Girls .

Mike Leigh ended the 20th century by striking out in a most unexpected direction with Topsy-Turvy , dealing with the relationship between Gilbert and Sullivan and the genesis and first production of The Mikado . It is in many ways a surprising departure: at heart, an oldfashioned backstage story, realised as a visually accurate period piece, and offering sumptuous and joyous extracts from The Mikado . The film points to Leigh's particular sensibility in the threads of unhappiness that run through several of the characters' lives, but, it's something of a rag-bag of ideas that never quite fuse into a successful vision. If nothing else, though, Topsy-Turvy demonstrates and confirms that Mike Leigh's imagination is not static and that he is undeniably very much an "auteur," while the number of awards and nominations it garnered, including those from the British critics and BAFTA, might indicate that appreciation of his gifts in his home country is increasing.

—Julian Petley, updated by Robyn Karney

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: