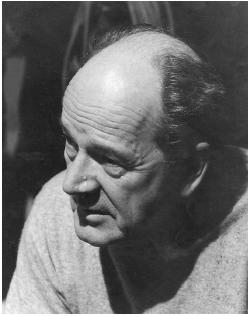

Ernst Lubitsch - Director

Nationality: German/American. Born: Berlin, 28 January 1892; became U.S. citizen, 1936. Education: Attended the Sophien Gymnasium. Family: Married 1) Irni (Helene) Kraus, 1922 (divorced 1930); 2) Sania Bezencenet (Vivian Gaye), 1935 (divorced 1943), one daughter. Career: Taken into Max Reinhardt Theater Company, 1911; actor, writer, then director of short films, from 1913; member of

Adolph Zukor's Europäischen Film-Allianz (Efa), 1921; joined Warner Brothers, Hollywood, 1923; began association with Paramount, 1928; began collaboration with writer Ernest Vajda, 1930; head of production at Paramount, 1935 (relieved of post after a year); left Paramount for three-year contract with 20th Century-Fox, 1938; suffered massive heart attack, 1943. Awards: Special Academy Award (for accomplishments in the industry), 1947. Died: In Hollywood, 29 November 1947.

Films as Director:

- 1914

-

Fräulein Seifenschaum (+ role); Blindkuh (+ role); Aufs Eis geführt (+ role)

- 1915

-

Zucker und Zimt (co-d, co-sc, role)

- 1916

-

Wo ist mein Schatz? (+ role); Schuhpalast Pinkus (+ role as Sally Pinkus); Der gemischte Frauenchor (+ role); Der G.m.b.H. Tenor (+ role); Der Kraftmeier (+ role); Leutnant auf Befehl (+ role); Das schönste Geschenk (+ role); Seine neue Nase (+ role)

- 1917

-

Wenn vier dasselbe Tun (+ co-sc, role); Der Blusenkönig (+ role): Ossis Tagebuch

- 1918

-

Prinz Sami (+ role); Ein fideles Gefängnis ; Der Fall Rosentopf (+ role); Der Rodelkavalier (+ co-sc); Die Augen der Mumie Mâ ; Das Mädel vom Ballett ; Carmen

- 1919

-

Meine Frau, die Filmschauspielerin; Meyer aus Berlin (+ role as apprentice); Das Schwabemädle; Die Austernprinzessin ; Rausch; Madame DuBarry ; Der lustige Ehemann (+ sc); Die Puppe (+ co-sc)

- 1920

-

Ich möchte kein Mann sein! (+ co-sc); Kohlhiesels Töchter (+ co-sc); Romeo und Julia im Schnee (+ co-sc); Sumurun (+ co-sc); Anna Boleyn

- 1921

-

Die Bergkatze (+ co-sc)

- 1922

-

Das Weib des Pharao

- 1923

-

Die Flamme ; Rosita

- 1924

-

The Marriage Circle ; Three Women; Forbidden Paradise (+ co-sc)

- 1925

-

Kiss Me Again (+ pr); Lady Windermere's Fan (+ pr)

- 1926

-

So This Is Paris (+ pr)

- 1927

-

The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg (+ pr)

- 1928

-

The Patriot (+ pr)

- 1929

-

Eternal Love (+ pr); The Love Parade (+ pr)

- 1930

-

Paramount on Parade (anthology film); Monte Carlo (+ pr)

- 1931

-

The Smiling Lieutenant (+ pr)

- 1932

-

The Man I Killed ( Broken Lullaby ) (+ pr); One Hour with You (+ pr); Trouble in Paradise (+ pr); If I Had a Million (anthology film)

- 1933

-

Design for Living (+ pr)

- 1934

-

The Merry Widow (+ pr)

- 1936

-

Desire (co-d, pr)

- 1937

-

Angel (+ pr)

- 1938

-

Bluebeard's Eighth Wife (+ pr)

- 1939

-

Ninotchka (+ pr)

- 1940

-

The Shop around the Corner (+ pr)

- 1941

-

That Uncertain Feeling (+ co-pr)

- 1942

-

To Be or Not to Be (co-source, co-pr)

- 1943

-

Heaven Can Wait (+ pr)

- 1946

-

Cluny Brown (+ pr)

- 1948

-

That Lady in Ermine (co-d)

Other Films:

- 1913

-

Meyer auf der Alm (role as Meyer)

- 1914

-

Die Firma Heiratet (Wilhelm) (role as Moritz Abramowski); Der Stolz der Firma (Wilhelm) (role as Siegmund Lachmann); Fräulein Piccolo (Hofer) (role); Arme Marie (Mack) (role); Bedingung—Kein Anhang! (Rye) (role); Die Ideale Gattin (role); Meyer als Soldat (role as Meyer)

- 1915

-

Robert und Bertram (Mack) (role); Wie Ich Ermordert Wurde (Ralph) (role); Der Schwarze Moritz (Taufstein and Berg) (role); Doktor Satansohn (Edel) (role as Dr. Satansohn); Hans Trutz im Schlaraffenland (Wegener) (role as Devil)

Publications

By LUBITSCH: articles—

"American Cinematographers Superior Artists," in American Cinematographer (Los Angeles), December 1923.

"Concerning Cinematography . . . as Told to William Stull," in American Cinematographer (Los Angeles), November 1929.

"Lubitsch's Analysis of Pictures Minimizes Director's Importance," in Variety (New York), 1 March 1932.

"Hollywood Still Leads . . . Says Ernst Lubitsch," interview with Barney Hutchinson, in American Cinematographer (Los Angeles), March 1933.

"A Tribute to Lubitsch, with a Letter in Which Lubitsch Appraises His Own Career," in Films in Review (New York), August/September 1951.

Letter to Herman Weinberg (10 July 1947), in Film Culture (New York), Summer 1962.

On LUBITSCH: books—

Verdone, Mario, Ernst Lubitsch , Lyon, 1964.

Baxter, John, The Hollywood Exiles , New York, 1976.

Huff, Theodore, An Index to the Films of Ernst Lubitsch , New York, 1976.

Poague, Leland, The Cinema of Ernst Lubitsch: The Hollywood Films , London, 1977.

Weinberg, Herman, The Lubitsch Touch: A Critical Study , 3rd revised edition, New York, 1977.

Carringer, R., and B. Sabath, Ernst Lubitsch: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1978.

Paul, William, Ernst Lubitsch's American Comedy , New York, 1983.

Prinzler, Hans Helmut, and Enno Patalas, editors, Lubitsch , Munich, 1984.

Cahiers du Cinéma/Cinématheque Française: Ernst Lubitsch , Paris, 1985.

Petrie, Graham, Hollywood Destinies: European Directors in Hollywood 1922–31 , London, 1985.

Bourget, Eithne, and Jean-Loup, Lubitsch: ou, La Satire Romanesque , Paris, 1987.

Nacache, Jacqueline, Lubitsch , Paris, 1987.

Hake, Sabine, Passions and Deceptions: The Early Films of Ernst Lubitsch , Princeton, 1992.

Bowman, Barbara, Master Space: Film Images of Capra, Lubitsch, Sternberg, and Wyler , Wesport, Connecticut, 1992.

Eyman, Scott, Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise , New York, 1993.

Harvey, James, Romantic Comedy in Hollywood: From Lubitsch to Sturges , New York, 1998.

On LUBITSCH: articles—

Merrick, Mollie, "Twenty-five Years of the 'Lubitsch Touch' in Hollywood," in American Cinematographer (Los Angeles), July 1947.

"E. Lubitsch Dead: Film Producer, 55," in New York Times , 1 December 1947.

"Ernst Lubitsch: A Symposium," in Screen Writer , January 1948.

Wollenberg, H.H., "Two Masters: Ernst Lubitsch and Sergei M. Eisenstein," in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1948.

"Lubitsch section" of Revue du Cinéma (Paris), September 1948.

"The Films of Ernst Lubitsch," special issue of Film Journal (Australia), June 1959.

"A Tribute to Lubitsch (1892–1947)," in Action! (Los Angeles), November/December 1967.

Eisenschitz, Bernard, "Lubitsch (1892–1947)," in Anthologie du Cinéma vol. 3, Paris, 1968.

"Lubitsch section" of Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), February 1968.

Eisner, Lotte, "Lubitsch and the Costume Film," chapter 4 in The Haunted Screen , Berkeley, 1969.

Weinberg, Herman, "Ernst Lubitsch: A Parallel to George Feydeau," in Film Comment (New York), Spring 1970.

Sarris, Andrew, "Lubitsch in the Thirties," in Film Comment (New York), Winter 1971/72 and Summer 1972.

Mast, Gerald, "The 'Lubitsch Touch' and the Lubitsch Brain," in The Comic Mind: Comedy and the Movies , Indianapolis, Indiana, 1973; revised edition, 1979.

McBride, J., "The Importance of Being Ernst," in Film Heritage (New York), Summer 1973.

Schwartz, N., "Lubitsch's Widow: The Meaning of a Waltz," in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1975.

Horak, Jan-Christopher, "The Pre-Hollywood Lubitsch," in Image (Rochester, New York), December 1975.

Whittemore, Don, and Philip Cecchettini, "Ernst Lubitsch," in Passport to Hollywood: Film Immigrants: Anthology , New York, 1976.

Baxter, John, "The Continental Touch," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), September 1976.

Bond, Kirk, "Ernst Lubitsch," in Film Culture (New York), no. 63–64, 1977.

Gillett, John, "Munich's Cleaned Pictures," in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1977/78.

Truffaut, François, "Lubitsch Was a Prince," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), May 1978.

McVay, D., "Lubitsch: The American Silent Films," in Focus on Film (London), April 1979.

Traubner, R., "Lubitsch Returns to Berlin," in Films in Review (New York), October 1984.

"Lubitsch section" of Cinéma (Paris), April 1985.

"Lubitsch section" of Positif (Paris), June and July/August 1986.

"Ernst Lubitsch," in Film Dope (London), February 1987.

Nave, B., "Aimer Lubitsch," in Jeune Cinéma (Paris), May/June 1987.

Cahir, L.C., "A Shared Impulse: The Significance of Language in Oscar Wilde's and Ernst Lubitsch's Lady Windermere's Fan ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 19, no. 1, January 1991.

Pratt, D.B., "'O, Lubitsch, Where Wert Thou?': Passion, the German Invasion, and the Emergence of the Name 'Lubitsch'," in Wide Angle (Baltimore), vol. 13, no. 1, January 1991.

Eyman, S., "Lubitsch, Pickford, and the Rosita War," in Griffithiana (Gemona), vol. 15, no. 44–45, May-September 1992.

Saada, Nicolas, "Lubitsch: Le poids de la grâce," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), no. 494, September 1995.

* * *

Ernst Lubitsch's varied career is often broken down into periods to emphasize the spectrum of his talents—from an actor in Max Reinhardt's Berlin Theater Company to head of production at Paramount. Each of these periods could well provide enough material for a sizeable book. It is probably most convenient to divide Lubitsch's output into three phases: his German films between 1913 and 1922; his Hollywood films from 1923 to 1934; and his Hollywood productions from 1935 till his death in 1947.

During the first half of Lubitsch's filmmaking decade in Germany he completed about nineteen shorts. They were predominantly ethnic slapsticks in which he played a "Dummkopf" character by the name of Meyer. Only three of these one- to five-reelers still exist. He directed eighteen more films during his last five years in Germany, almost equally divided between comedies—some of which anticipate the concerns of his Hollywood works—and epic costume dramas. Pola Negri starred in most of these historical spectacles, and the strength of her performances together with the quality of Lubitsch's productions brought them both international acclaim. Their Madame Dubarry (retitled Passion in the United States) was not only one of the films responsible for breaking the American blockade on imported German films after World War I, but it also began the "invasion" of Hollywood by German talent.

Lubitsch came to Hollywood at Mary Pickford's invitation. He had hoped to direct her in Faust , but they finally agreed upon Rosita , a costume romance very similar to those he had done in Germany. After joining Warner Brothers, he directed five films that firmly established his thematic interests. The films were small in scale, dealt openly with sexual and psychological relationships in and out of marriage, refrained from offering conventional moral judgments, and demystified women. As Molly Haskell and Marjorie Rosen point out, Lubitsch created complex female characters who were aggressive, unsentimental, and able to express their sexual desires without suffering the usual pains of banishment or death. Even though Lubitsch provided a new and healthy perspective on sex and increased America's understanding of a woman's role in society, he did so only in a superficial way. His women ultimately affirmed the status quo. The most frequently cited film from this initial burst of creativity, The Marriage Circle , also exhibits the basic narrative motif found in most of Lubitsch's work—the third person catalyst. An essentially solid relationship is temporarily threatened by a sexual rival. The possibility of infidelity serves as the occasion for the original partners to reassess their relationship. They acquire a new self-awareness and understand the responsibilities they have towards each other. The lovers are left more intimately bound than before. This premise was consistently reworked until The Merry Widow in 1934.

The late 1920s were years of turmoil as every studio tried to adapt to sound recording. Lubitsch, apparently, was not troubled at all; he considered the sound booths nothing more than an inconvenience, something readily overcome. Seven of his ten films from 1929 to 1934 were musicals, but not of the proscenium-bound "all-singing, all-dancing" variety. Musicals were produced with such prolific abandon during this time (what better way to exploit the new technology?) that the public began avoiding them. Film histories tend to view the period from 1930 to 1933 as a musical void, yet it was the precise time that Lubitsch was making significant contributions to the genre. As Arthur Knight notes, "He was the first to be concerned with the 'natural' introduction of songs into the development of a musical-comedy plot." Starting with The Love Parade , Lubitsch eliminated the staginess that was characteristic of most musicals by employing a moving camera, clever editing, and the judicial use of integrated musical performance, and in doing so constructed a seminal film musical format.

In 1932 Lubitsch directed his first non-musical sound comedy, Trouble in Paradise. Most critics consider this film to be, if not his best, then at least the complete embodiment of everything that has been associated with Lubitsch: sparkling dialogue, interesting plots, witty and sophisticated characters, and an air of urbanity—all part of the well-known "Lubitsch Touch." What constitutes the "Lubitsch Touch" is open to continual debate, the majority of the definitions being couched in poetic terms of idolization. Andrew Sarris comments that the "Lubitsch Touch" is a counterpoint of poignant sadness during a film's gayest moments. Leland A. Poague sees Lubitsch's style as being gracefully charming and fluid, with an "ingenious ability to suggest more than he showed. . . ." Observations like this last one earned Lubitsch the unfortunate moniker of "director of doors," since a number of his jokes relied on what unseen activity was being implied behind a closed door.

Regardless of which romantic description one chooses, the "Lubitsch Touch" can be most concretely seen as deriving from a standard narrative device of the silent film: interrupting the dramatic interchange by focusing on objects or small details that make a witty comment on or surprising revelation about the main action. Whatever the explanation, Lubitsch's style was exceptionally popular with critics and audiences alike. Ten years after arriving in the United States he had directed eighteen features, parts of two anthologies, and was recognized as one of Hollywood's top directors.

Lubitsch's final phase began when he was appointed head of production at Paramount in 1935, a position that lasted only one year. Accustomed to pouring all his energies into one project at a time, he was ineffective juggling numerous projects simultaneously. Accused of being out of step with the times, Lubitsch updated his themes in his first political satire, Ninotchka , today probably his most famous film. He continued using parody and satire in his blackest comedy, To Be or Not to Be , a film well liked by his contemporaries, and today receiving much reinvestigation. If Lubitsch's greatest talent was his ability to make us laugh at the most serious events and anxieties, to use comedy to make us more aware of ourselves, then To Be or Not to Be might be considered the consummate work of his career.

Lubitsch, whom Gerald Mast terms the greatest technician in American cinema after Griffith, completed only two more films. At his funeral in 1947, Mervyn LeRoy presented a fitting eulogy: "he advanced the techniques of screen comedy as no one else has ever done. Suddenly the pratfall and the double-take were left behind and the sources of deep inner laughter were tapped."

—Greg S. Faller

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: