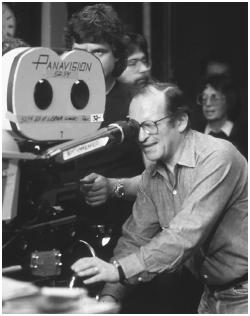

Sidney Lumet - Director

Nationality:

American.

Born:

Philadelphia, 25 June 1924.

Education:

Professional Children's School, New York; Columbia University

extension school.

Military Service:

Served in Signal Corps, U.S. Army, 1942–46.

Family:

Married 1) Rita Gam (divorced); 2) Gloria Vanderbilt, 1956 (divorced,

1963); 3) Gail Jones, 1963 (divorced, 1978); 4) Mary Gimbel, 1980; two

daughters.

Career:

Acting debut in Yiddish Theatre production, New York, 1928; Broadway

debut in

Dead End

, 1935; film actor, from 1939; stage director, off-Broadway, from 1947;

assistant director, then director, for TV, from 1950.

Awards:

Directors Guild Awards, for

Twelve Angry Men

, 1957, and

Long Day's Journey into Night

, 1962; D.W. Griffith Award of the Directors Guild of America, 1993.

Address:

c/o LAH Film Corporation, 1775 Broadway, New York, NY 10019, U.S.A.

Films as Director:

- 1957

-

Twelve Angry Men

- 1958

-

Stage Struck

- 1959

-

That Kind of Woman

- 1960

-

The Fugitive Kind

- 1962

-

A View from the Bridge ; Long Day's Journey into Night

- 1964

-

Fail Safe

- 1965

-

Pawnbroker ; Up from the Beach ; The Hill

- 1966

-

The Group (+ pr)

- 1967

-

The Deadly Affair (+ pr)

- 1968

-

Bye Bye Braverman (+ pr); The Seagull (+ pr)

- 1969

-

Blood Kin (doc) (co-d, co-pr)

- 1970

-

King: A Filmed Record . . . Montgomery to Memphis (doc) (co-d, co-pr); The Appointment ; The Last of the Mobile Hot Shots

- 1971

-

The Anderson Tapes

- 1972

-

Child's Play

- 1973

-

The Offense ; Serpico

- 1974

-

Lovin' Molly ; Murder on the Orient Express

- 1975

-

Dog Day Afternoon

- 1977

-

Equus ; Network

- 1978

-

The Wiz

- 1980

-

Just Tell Me What You Want (+ pr)

- 1981

-

Prince of the City

- 1982

-

Deathtrap ; The Verdict

- 1983

-

Daniel

- 1984

-

Garbo Talks

- 1986

-

Power ; The Morning After

- 1988

-

Running on Empty

- 1989

-

Family Business

- 1990

-

Q & A (+ sc)

- 1992

-

A Stranger among Us

- 1993

-

Guilty as Sin

- 1997

-

Night Falls on Manhattan (+ sc); Critical Care (+ pr)

- 1999

-

Gloria

- 2000

-

Whistle

Other Films:

- 1939

-

One Third of a Nation (Murphy) (role as Joey Rogers)

- 1940

-

Journey to Jerusalem (role as youthful Jesus)

- 1990

-

Listen Up! The Lives of Quincy Jones (role)

Publications

By LUMET: book—

Making Movies , New York, 1995.

By LUMET: articles—

Interview with Peter Bogdanovich, in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Winter 1960.

"Sidney Lumet," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), December 1963/January 1964.

"Keep Them on the Hook," in Films and Filming (London), October 1964.

Interview with Luciano Dale, in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Fall 1971.

"Sidney Lumet on the Director," in Movie People: At Work in the Business , edited by Fred Baker, New York, 1972.

Interview with Susan Merrill, in Films in Review (New York), November 1973.

Interviews with Gordon Gow, in Films and Filming (London), May 1975 and May 1978.

Interview with Dan Yakir, in Film Comment (New York), December 1978.

Interview with Michel Ciment and O. Eyquem, in Positif (Paris), February 1982.

"Delivering Daniel ," an interview with Richard Combs, in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), January 1984.

Interview with K. M. Chanko, in Films in Review (New York), October 1984.

Interview with M. Burke, in Stills (London), February 1987.

"Sidney Lumet: Lion on the Left," an interview with G. Smith, in Film Comment (New York), July/August 1988.

"That's the Way It Happens," an interview with Gavin Smith, in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1992.

"L'homme en colère. Une étrangère parmi nous," an interview with Pierre Murat, in Télérama (Paris), 6 January 1993.

Interview with Heike-Melba Fendel, in EPD Film (Frankfurt), May 1993.

On LUMET: books—

Bowles, Stephen, Sidney Lumet: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1979.

De Santi, Gualtiero, Sidney Lumet , Florence, 1988.

Cunningham, Frank R., Sidney Lumet: Film and Literary Vision , Lexington, Kentucky, 1991.

Boyer, Jay, Sidney Lumet , New York, 1993.

On LUMET: articles—

Petrie, Graham, "The Films of Sidney Lumet: Adaptation as Art," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Winter 1967/68.

Rayns, Tony, "Across the Board," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1974.

Sidney Lumet Section of Cinématographe (Paris), January 1982.

Chase, D., "Sidney Lumet Shoots The Verdict ," in Millimeter (New York), December 1982.

Shewey, D., "Sidney Lumet: The Reluctant Auteur," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), December 1982.

"TV to Film: A History, a Map, and a Family Tree," in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), February 1983.

"Sidney Lumet," in Film Dope (London), June 1987.

Tempel, M. van den, "Chroniqueur van New York," in Skoop , May 1991.

Fleming, M., "New York Banks on Hudson Studio," in Variety , 15 June 1992.

Costello, D.P., "Sidney Lumet's Long Day's Journey into Night ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), April 1994.

Leventhal, L., "City of Mind," in Variety's On Production (Los Angeles), no. 10, 1996.

Callahan, M., "A Streetwise Legend Sticks to His Guns," in New York Magazine , 26 May 1997.

Lopate, P., "Sidney Lumet," in Film Comment (New York), July/August 1997.

Sabbe, M., "Sidney Lumet," in Film en Televisie + Video (Brussels), September 1997.

Wickbom, Kaj, in Filmrutan (Sundsvall), Winter 1998.

* * *

Although Sidney Lumet has applied his talents to a variety of genres (drama, comedy, satire, caper, romance, and even a musical), he has proven himself most comfortable and effective as a director of serious psychodramas and was most vulnerable when attempting light entertainments. His Academy Award nominations, for example, have all been for character studies of men in crisis, from his first film, Twelve Angry Men , to The Verdict. Lumet was, literally, a child of the drama. At the age of four he was appearing in productions of the highly popular and acclaimed Yiddish Theatre in New York. He continued to act for the next two decades but increasingly gravitated toward directing. At twenty-six he was offered a position as an assistant director with CBS television. Along with John Frankenheimer, Robert Mulligan, Martin Ritt, Delbert Mann, George Roy Hill, Franklin Schaffner, and others, Lumet quickly won recognition as a competent and reliable director in a medium where many faltered under the pressures of producing live programs. It was in this environment that Lumet learned many of the skills that would serve him so well in his subsequent career in films: working closely with performers, rapid preparation for production, and working within tight schedules and budgets.

Because the quality of many of the television dramas was so impressive, several of them were adapted as motion pictures. Reginald Rose's Twelve Angry Men brought Lumet to the cinema. Although Lumet did not direct the television production, his expertise made him the ideal director for this low-budget film venture.

Twelve Angry Men was an auspicious beginning for Lumet. It was a critical and commercial success and established Lumet as a director skilled at adapting theatrical properties to motion pictures. Fully half of Lumet's complement of films have originated in the theater. Another precedent set by Twelve Angry Men was Lumet's career-long disdain for Hollywood.

Lumet prefers to work in contemporary urban settings, especially New York. Within this context, Lumet is consistently attracted to situations in which crime provides the occasion for a group of characters to come together. Typically these characters are caught in a vortex of events they can neither understand nor control but which they must work to resolve.

Twelve Angry Men explores the interaction of a group of jurors debating the innocence or guilt of a man being tried for murder; The Hill concerns a rough group of military men who have been sentenced to prison; The Deadly Affair involves espionage in Britain; The Anderson Tapes revolves around the robbery of a luxury apartment building; Child's Play , about murder at a boy's school, conveys an almost supernatural atmosphere of menace; Murder on the Orient Express, Dog Day Afternoon , and The Verdict all involve attempts to find the solution to a crime, while Serpico and Prince of the City are probing examinations of men who have rejected graft practices as police officers.

Lumet's protagonists tend to be isolated, unexceptional men who oppose a group or institution. Whether the protagonist is a member of a jury or party to a bungled robbery, he follows his instincts and intuition in an effort to find solutions. Lumet's most important criterion is not whether the actions of these men are right or wrong but whether the actions are genuine. If these actions are justified by the individual's conscience, this gives his heroes uncommon strength and courage to endure the pressures, abuses, and injustices of others. Frank Serpico, for example, is the quintessential Lumet hero in his defiance of peer group authority and the assertion of his own code of moral values.

Nearly all the characters in Lumet's gallery are driven by obsessions or passions that range from the pursuit of justice, honesty, and truth to the clutches of jealousy, memory, or guilt. It is not so much the object of their fixations but the obsessive condition itself that intrigues Lumet. In films like The Fugitive Kind, A View from the Bridge, Long Day's Journey into Night, The Pawnbroker, The Seagull, The Appointment, The Offense, Lovin' Molly, Network, Just Tell Me What You Want , and many of the others, the protagonists, as a result of their complex fixations, are lonely, often disillusioned individuals. Consequently, most of Lumet's central characters are not likable or pleasant, and sometimes not admirable figures. And, typically, their fixations result in tragic or unhappy consequences.

Lumet's fortunes have been up and down at the box office. One explanation seems to be his own fixation with uncompromising studies of men in crisis. His most intense characters present a grim vision of idealists broken by realities. From Val in A View from the Bridge and Sol Nazerman in The Pawnbroker to Danny Ciello in Prince of the City , Lumet's introspective characters seek to penetrate the deepest regions of the psyche.

Lumet's recently published memoir about his life in film, Making Movies , is extremely lighthearted and infectious in its enthusiasm for the craft of moviemaking itself. This stands in marked contrast to the tone and style of most of his films. Perhaps Lumet's signature as a director is his work with actors—and his exceptional ability to draw high-quality, sometimes extraordinary performances from even the most unexpected quarters: Melanie Griffith's believable undercover policewoman in A Stranger among Us and Don Johnson's smooth-talking sociopath in Guilty as Sin. These two latest examples of the "Lumet touch" with actors demonstrate that he has not lost it.

—Stephen E. Bowles, updated by John McCarty