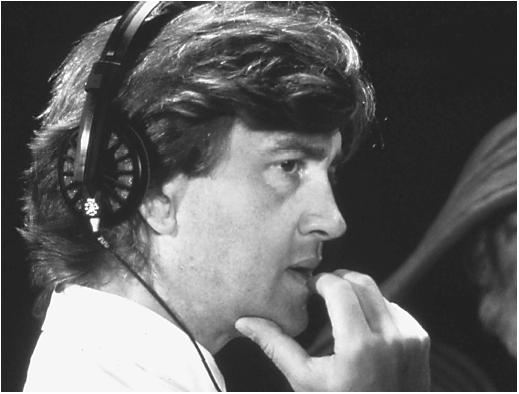

David Lynch - Director

Nationality:

American.

Born:

Missoula, Montana, 20 January 1946.

Education:

High school in Alexandria, Virginia; Corcoran School of Art, c. 1964;

Boston Museum School, 1965; Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art,

1965–69; American Film Institute Centre for Advanced Studies,

studying under Frank Daniel, 1970.

Family:

Married 1) Peggy Reavey, 1967 (divorced, 1974), one daughter,

writer/director Jennifer Lynch; 2) Mary Fisk, 1977 (divorced, 1987), one

son, Austin.

Career:

Spent five years making

Eraserhead

, Los Angeles, 1971–76; worked as paperboy and shed-builder, late

1970s; invited by Mel Brooks to direct

The Elephant Man

, 1980; with Mark Frost, made

Twin Peaks

for video (two-hour version) and as TV series, 1989. Executive producer

and writer of the CD-rom video game

Woodcutters from Fiery Ships

, 2000.

Awards:

National Society of Film Critics Awards for Best Film and Best Director,

for

Blue Velvet

, 1986; Palme d'Or, Cannes Festival, for

Wild at Heart

, 1990.

Films as Director:

- 1968

-

The Alphabet (short) (sc)

- 1970

-

The Grandmother (short) (sc)

- 1978

-

Eraserhead (sc)

- 1980

-

The Elephant Man (co-sc)

- 1984

-

Dune (sc)

- 1986

-

Blue Velvet (sc)

- 1988

-

episode in Les Français vus par ...

- 1990

-

Wild at Heart (sc)

- 1992

-

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (co-sc + co-pr, role as Gordon Cole)

- 1995

-

episode in Lumiere et compagnie

- 1997

-

Lost Highway (sc)

- 1999

-

The Straight Story (+ mus)

- 2001

-

Mulholland Drive (co-sc, exec pr)

Other Films:

- 1988

-

Zelly and Me (role as Willie)

- 1991

-

The Cabinet of Dr. Ramirez (exec pr)

- 1994

-

Nadja (exec pr, role as Morgue Attendant)

- 1997

-

Pretty as a Picture: The Art of David Lynch (for TV) (as himself)

Publications

By LYNCH: books—

Welcome to Twin Peaks: An Access Guide to the Town , with Richard Saul Wurman and Mark Frost, London, 1991.

Images , New York, 1994.

Lost Highways , New York, 1997.

Lynch on Lynch , with Chris Rodley, London, 1999.

By LYNCH: articles—

Interview with Serge Daney and Charles Tesson, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), April 1981.

Interview with D. Chute, in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1986.

Interview with K. Jaehne and L. Bouzereau, in Cineaste (New York), vol. 15, no. 3, 1987.

Interview with A. Caron and M. Girard, in Séquences (Montreal), February 1987.

Interview with D. Marsh and A. Missler, in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), March 1987.

Interview with Jane Root, in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), April 1987.

Interview with D. Breskin, in Rolling Stone , September 6, 1990.

Interview with M. Ciment and H. Niogret, in Positif , October 1990.

" Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me : The Press Conference," with Scott Murray, in Cinema Papers (Fitzroy), August 1992.

"Naked Lynch," an interview with Geoff Andrew, in Time Out (London), 18 November 1992.

Interview with Bill Krohn and Vincent Ostria, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), July-August 1994.

"A Passage from India," an interview with G. Solman, in Variety's On Production (Los Angeles), no. 2, 1997.

"David Lynch," an interview with Philippe Rouyer and Michael Henry, in Positif (Paris), January 1997.

"Lynch Law," an interview with D. Yaffe, in Village Voice (New York), 25 February 1997.

"Highway to Hell," an interview with Stephen Pizzello, in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), March 1997.

"The Road to Hell," an interview with Dominic Wells, in Time Out (London), 13 August 1997.

On LYNCH: books—

Kaleta, Kenneth C., David Lynch , New York, 1993.

Chion, Michel, and Julian, Robert, David Lynch , London, 1995.

Nochimson, Martha P., The Passion of David Lynch: Wild at Heart in Hollywood , Austin, 1997.

On LYNCH: articles—

Hinson, H., "Dreamscapes," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), December 1984.

David Lynch section of Revue du Cinéma (Paris), February 1987.

Combs, Richard, "Crude Thoughts and Fierce Forces," in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), April 1987.

French, Sean, "The Heart of the Cavern," in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1987.

"David Lynch," in Film Dope (London), June 1987.

McDonagh, M., "The Enigma of David Lynch," in Persistence of Vision (Maspeth, New York), Summer 1988.

Gehr, R., "The Angriest Painter in the World," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), April 1989.

Saada, N., "David Lynch," in Cahiers du Cinéma , June 1990.

Zimmer, J., "David Lynch," in Revue du Cinéma , July/August 1990.

Woodward, Robert B., "Wild at Heart . . . Weird on Top," in Empire (London), September 1990.

Hoberman, J., and Jonathan Rosenbaum, "Curse of the Cult People," in Film Comment , January/February 1991.

Sante, Luc, "The Rise of the Baroque Directors," in Vogue , September 1992.

Jankiewicz, P., "Lynch's Hall of Freaks," in Film Threat , October 1992.

Hampton, Howard, "David Lynch's Secret History of the United States," in Film Comment , May/June 1993.

Rastelli, D., "Non toccate la mia giacca," in Cineforum (Bergamo), July-August 1996.

Wyatt, J., "David Lynch Keeps His Head," in Premiere (Boulder), September 1996.

"Das Universum David Lynch," a dossier, in Zoom (Zürich), no. 3, March 1997.

Dossier, in Filmihullu (Helsinki), no. 4–5, 1997.

Biodrowski, S., "David Lynch," in Cinefantastique (Forest Park), no. 10, 1997.

Szebin, F.C. and Biodrowski, S., "David Lynch," in Cinefantastique (Forest Park), no. 12, 1997.

Leitch, Thomas M., "The Hitchcock Moment," in Hitchcock Annual (Gambier), 1997–98.

* * *

The undoubted perversity that runs throughout the works of David Lynch extends to his repeated and unexpected career turns: coming off the semi-underground Eraserhead to make the semi-respectable The Elephant Man with a distinguished British cast; then bouncing into a Dino de Laurentiis mega-budget science-fiction fiasco, Dune; creeping back with the seductive and elusive small-town mystery of Blue Velvet; capping that by transferring his uncompromising vision of lurking sexual violence to American network television in Twin Peaks; and alienating the viewers of that bizarre soap with the rambling, intermittently stupefying, road movie Wild at Heart. Although there are recognisable Lynchian elements, with both Eraserhead and Blue Velvet —his two most commercially and critically successful movies—leaking images and ideas into the pairs of movies that followed them up, Lynch has proved surprisingly difficult to pin down. Given one Lynch movie, it has been—until the slightly too self-plagiaristic Wild at Heart —almost impossible to predict the next step. A painter and animator—his first films are Svankmajer-style shorts The Grandmother and Alphabet —Lynch came into the film industry through the back door, converting his thesis movie into Eraserhead on a shooting schedule that stretched over some years and required the eternal soliciting of money from friends, like Sissy Spacek, who had gone on to do well.

Eraserhead is one of the rare cult movies that deserves its cult reputation, although it is a hard movie to sit still through for a second time around. Set in a monochrome fantasy world that suggests the slums of Oz, it follows a pompadoured drudge, Henry (John Nance), through his awful life in a decaying apartment building, with occasional bursts of light relief from the fungus-cheeked songstress behind the radiator, and winds up with two extraordinarily bizarre and horrid fantasy sequences, one in which Henry's head falls off and is mined for indiarubber to be used in pencil erasers, and the other in which he cuts apart his skinned fetus of a mutant child and is deluged with a literal tide of excrement. Without really being profound, the film manages to worm its way into the hearts of the college crowd, cannily appealing—in one of Lynch's trademarks—to intellectuals who relish the multiple allusions and evasive "meanings" of the film, and to horror movie fans who just like to go along with the extreme imagery. It was this combination, perhaps, that caught the eye of Mel Brooks' Brooksfilms, which was looking to branch into more serious work and tapped Lynch to bring its first foray, The Elephant Man , to the screen. This true story had been the basis of a successful Broadway play. But Lunch was given free reign to mine the historical record for inspiration instead as the film was not drawn from the play. With The Elephant Man , also in black and white and laden with the steamy industrial imagery of Eraserhead , Lynch, cued perhaps by the poignance of John Hurt's under-the-rubber performance and the presence of the sort of cast (Anthony Hopkins, John Gielgud, Freddie Jones, Michael Elphick) one would expect from some BBC-TV Masterpiece Theatre serial, opts for a more humanist approach, mellowing the sheer nastiness of the first film. In the finale, as the mutant John Merrck attends a lovingly recreated Victorian magic show, Lynch even pays homage to the gentle magician whose The Man with the Indiarubber Head might be cited as a precursor to Eraserhead , Georges Méliès.

Dune is a folly by anyone's standards, and the re-cut television version—which Lynch opted to sign with the Director's Guild pseudonym Allan Smithee—is no help in sorting out the multiple plot confusions of Frank Herbert's pretentious and unfilmable science-fiction epic. Hoping for a fusion of Star Wars and Lawrence of Arabia , De Laurentiis—who stuck by Lynch throughout the troubled $40 million production—wound up with a turgid mess, overloaded with talented performers in nothing roles, that only spottily seems to have engaged Lynch's interest, mostly when there are monsters on screen or when Kenneth McMillan is campily overdoing his perverse and evil emperor act. Dune landed Lynch in the doldrums, and his comeback movie, also for the forgiving De Laurentiis, was very carefully crafted to evoke the virtues and cult commercial appeal of Eraserhead without seeming a throwback. Drawing on Shadow of a Doubt , Lynch made a small-town mystery that deigns to work on a plot level, and then shot it through with his own cruel insights into the teeming, insectoid nightmare that exists beneath the red, white, and blue prettiness of the setting, coaxing sinister meaning out of resonant pop songs like "Blue Velvet" and "In Dreams," and establishing the core of a repertory company—Kyle MacLachlan of Dune , Isabella Rossellini, Laura Dern—who would recur in his next projects. Blue Velvet , far more than the muddy Dune , established Lynch as a master of colour in addition to his black and white skills, and also, through his handling of human monster Dennis Hopper's abuse of Rossellini, as a chronicler of extreme emotions, often combining sex and violence in one disturbing, yet undeniably appealing package.

Twin Peaks , a television series Lynch devised and for which he directed the pilot film, is a strange offshoot of Blue Velvet , set in a similar town and with MacLachlan again the odd investigator of a crime the nature of which is hard to define. Although it lacks the explicit tone of the earlier film, in which Dennis Hopper is given to basic outbursts like "baby wants to fuck!," Twin Peaks is also insidiously fascinating, using the labyrinthine plot convolutions of the typical soap opera—among other things, the show is a lineal descendant of Peyton Place —in addition to the puzzle-solving twists of the murder mystery to probe under the surface of a folksy America of junk food and picket fences. As a reaction to the eerie restraint of Twin Peaks, Wild at Heart is an undisciplined road film which evokes Elvis in Nicolas Cage's subtly overwrought performance and straggles along towards its Wizard of Oz finale, passing by the high points of Lynch's career (featuring players and jokes from all his earlier movies) as it plays out its couple-on-the-run storyline in a surprisingly straightforward and above-board manner. With Willem Dafoe's dirty-teeth monster replacing Dennis Hopper's gas-sniffing gangster, Wild at Heart echoes the violent and sexual excesses of Blue Velvet , including one exploding head stunt out of The Evil Dead and many heavy-metal-scored, heavy-duty sex scenes, but suffers from its superficiality, predictability, and a cast of characters so unlikable that we don't give a damn about the fates of any of them. Notes critic Hen Hanke: " Wild at Heart is nothing but a con game—a filmic Emperor's New Clothes. At least that's what we hope it is, because of this is truly how Lynch views the world, he must be one of the most unhappy people on the planet."

Both a genuine artist (say his supporters) and a cunning commercial survivor, Lynch appeared—in the minds of many critics—to be one of the best hopes for cinema in the 1990s. As of 1995, however, his promise as a savior had yet to be fulfilled. Unable to get the illfated Twin Peaks out of his system after it went unceremoniously off the air without a resolution, Lynch launched a theatrical version of his TV show, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. Ironically, it turned out to be a prequel to the events portrayed in the series rather than a sequel, so to date we are still left without a resolution to the labyrinthine mysteries surrounding the puzzle of "who killed Laura Palmer?" Overlong and oddly underheated, it was a commercial bomb, even with hardcore Peaks fans.

Not just inclined to listen to the supporters who extol him as an artist but heed them as well, Lynch made his next film, Lost Highway , expressly for this rabid group, it seems. Based on a dream of Lynch's, the film unfolds with the logic of a dream — which to say, no logic at all. It's about a man who may or may not be an escapee from prison, who may or may not have killed his wife, and who may or may not be being pursued by the authorities, gangsters, and a host of bizarro Lynchian characters. As self-indulgent as many of Lynch's previous works, it's artsy-fartsy pretentiousness is a whole lot more difficult to defend, however.

By contrast, Lynch's next film, The Straight Story , seems almost like a rejection of everything his most rabid supporters hold dear about him. Superficially at least, it is the most un-Lynch-like film in the director's body of work: A gentle, life-affirming, straight-fromthe-heart, family-oriented tribute to the honesty, ideals, and tenacity of Middle America with a G rating and not a baroque or pretentious bone in its warm and fuzzy body.

—Kim Newman, updated by John McCarty

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: