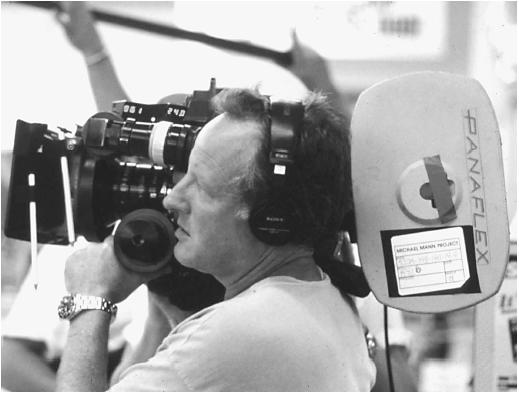

Michael Mann - Director

Nationality: American. Born: Chicago, Illinois, 5 February 1943. Education: University of Wisconsin, 1965; London Film School, 1967. Family: Married to artist Summer Mann. Career: Directed shorts, commercials, and documentaries in England, 1967–72; wrote episodes for television series Starsky and Hutch and Police Story and created Vega$ and Miami Vice; directorial debut, The Jericho Mile (TV movie), 1979; screen debut, Thief , 1981. Awards: Directors Guild of America Best Director Award, 1980, for The Jericho Mile; Emmy Award for Outstanding Writing in a Limited Series or Special, 1980, for The Jericho Mile; Cognac Festival du Film Policier Critics Award, for Manhunter , 1987; National Board of Review Freedom of Expression Award, 1999, Golden Satellite Award for Best Director, 2000, and Writers Guild of America Paul Selvin Honorary Award (with Eric Roth), 2000, all for The Insider . Agent: Jeff Berg, International Creative Management, 8899 Beverly Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90048, U.S.A.

Films as Director:

- 1979

-

The Jericho Mile (for TV) (+ sc, exex-pr)

- 1981

-

Thief (+ co-sc + exec-pr)

- 1983

-

The Keep (+ co-sc)

- 1986

-

Manhunter (+ sc, pr)

- 1989

-

L.A. Takedown (for TV) (+ exec-pr)

- 1992

-

The Last of the Mohicans (+ co-sc, pr)

- 1995

-

Heat (+ co-sc, pr)

- 1999

-

The Insider (+ co-sc, pr)

Other Films:

- 1978

-

Vega$ (for TV) (sc); Straight Time (sc, uncredited)

- 1980

-

Swan Song (for TV) (sc)

- 1986

-

Band of the Hand (exec-pr)

- 1990

-

Drug Wars: The Camarena Story (TV mini-series) (exec-pr, co-sc)

- 1992

-

Drug Wars: The Cocaine Cartel (TV mini-series) (exec-pr)

Publications

By MANN: articles—

"Four-Minute Mile: Michael Mann Interviewed," in Films & Filming , 1980.

"An Interview with the Director of Thief ," in Rolling Stone , 1981.

"Castle Keep ," in Film Comment , 1983.

"Wars and Peace," in Sight and Sound , 1992.

"Brave Attempt/Mann Made," an interview with Brian Case and Geoff Andrew, in Time Out (London), 4 November 1992.

"Mann to Man," an interview with Geoff Andrew, in Time Out (London), 17 January 1996.

"Tommy Boy," in Interview , January 1997.

On MANN: articles—

Greco, M., "Up and Coming: Michael Mann," in Film Comment , 1980.

Murphy, K., "Communion," in Film Comment , 1991.

Smith, G., "Mann Hunters," in Film Comment , 1992.

Ansen, David, and D. Foote, "Mann in the Wilderness," in News-week , 1992.

Schruers, F., "Mann Overboard," in Premiere , 1992.

Hooper, J., "Mann and Mohican," in Esquire, 1992.

Lombardi, John, "What a Piece of Work Is Mann," in Gentleman's Quarterly , 1992.

Chiacchiari, Federico, and G. A. Nazzaro, in Cineforum (Bergamo), January-February 1996.

Combs, Richard, "Michael Mann: Becoming," in Film Comment (New York), March-April 1996.

Schnelle, F., in EPD Film (Frankfurt), March 1996.

"Bob and Al in the Coffee Shop," in Sight and Sound (London), March 1996.

Kit, Z., "Welcome to the Dark Side," in Written By. Journal: The Writers Guild of America, West (Los Angeles), February 1997.

* * *

Michael Mann's cinematic landscape is the mean streets of urban neo-noir. His stylistic signature is a hip, almost neon look, the images sharply edited and backed by adrenalin-pumping music. Given the razzle-dazzle MTV approach he brings to his craft, it is ironic that he started out wanting to be a writer. However, while attending the

Mann transferred to the London Film School in 1965 for training and graduated two years later. Like a number of contemporary directors, he got his start making television commercials, and he has carried over many of the stylistic ingredients of commercials into his subsequent film work.

Mann paid his dues in Hollywood writing episodes for TV cop shows of the 1970s, such as Starsky and Hutch and Joseph Wambaugh's Police Story ; for the ABC network he wrote the pilot episode of Vega$ , a short-lived Robert Urich private-eye series whose setting lent itself naturally to Mann's "neon look." By this time a specialist in the genre the French call roman policier , Mann had little difficulty convincing the network to give him a shot at writing and directing a feature film in a similar vein for its growing made-for-TV movie division. The result was The Jericho Mile (1979), which replaced the sun-drenched mean streets of Starsky and Hutch and the often rain-slicked ones of Police Story with the pallid walls of Folsom Prison. A hard-hitting drama about a convicted murderer (Peter Strauss) who survives the brutality of his surroundings and regains his self-respect by striving to become an Olympic runner, the well-received film added considerable luster to the often maligned TV movie form and won Mann an Emmy award. It also landed him a contract to make his theatrical film debut.

Turning again to his chosen milieu—the seedy world of crime and criminals—Mann wrote and directed Thief (1981), the gritty tale (with echoes of the classic Dassin film Rififi) of a safecracker who tries to make one last score and go straight, only to dig himself in even deeper. James Caan played the title role in the doom-laden thriller, a thematic and stylistic throwback to the classic films noir of the 1940s, but updated with the hip look and, especially, sound (courtesy here of Tangerine Dream) that are Mann's trademark.

Mann segued from Thief to The Keep (1983), based on F. Paul Wilson's novel about German soldiers who encounter a vampiric presence in the title fortress during World War II. Mann again brought considerable stylistic verve to the fantastic drama, but perhaps because he was in unfamiliar territory—the Carpathian mountains rather than the streets of L.A. and Chicago—the film failed to come together. Critics and audiences found it to be incomprehensible. It went belly-up at the box office and Mann went back to TV to create Miami Vice , one of the most influential cop series of the 1980s, and Crime Story. The former was a glitzy roman policier aimed at the MTV generation, while the latter was a period noir series with a neonoir look aimed at older viewers. Mann also directed a mini-series docudrama about the murder of narcotics agent Enrique Camarena called The Drug Wars (1990).

In between his TV work, Mann returned to the big screen to make one of his best and most underrated films, Manhunter (1986), based on the novel Red Dragon by Thomas Harris, in which the author introduced his master serial killer character Hannibal "the Cannibal" Lecter to the public. (He is played in the film by Brian Cox.) Produced by Dino De Laurentis's DEG Entertainment, Manhunter failed to get much of a promotional boost due to DEG's financial collapse and went nowhere at the box office. It was left to director Jonathan Demme and star Anthony Hopkins to make "Hannibal the Cannibal" a household name with Silence of the Lambs (1991), their Academy Award-winning screen version of Harris's sequel to Red Dragon. Mann partisans as well as many thriller fans consider Manhunter to be the superior work, however.

As he had done with The Keep , Mann shifted gears entirely with The Last of the Mohicans (1992), this time more successfully. It is a harshly beautiful—and definitive—version of James Fenimore Cooper's oft-filmed novel about the French and Indian War. Mann refused to take the politically correct route of making his Native American characters helpless, long-suffering victims. Instead, the film restores their dignity by restoring their historical fearsomeness as warriors, something the movies have been timid about doing for decades. In fact, Wes Studi's ferocious and very human villain Magua—who hungers as much for self-respect as for revenge—lingers in the memory more than does the film's hero, Hawkeye, played by Daniel Day-Lewis. Though the film's period milieu (with the mountains of North Carolina making a convincing stand-in for the 18th-century Adirondacks) is atypical of Mann, its kinetic mixture of sight and sound (the music score is remarkable) is all Mann. A moving saga of America's past, it is one of the most exciting adventure movies of recent times.

Heat returned Mann to the mean streets of urban America. The film is notable for its first-time pairing of gangster movie icons Al Pacino and Robert De Niro as the drama's opposing forces (although this dynamic duo shares little screen time together). A sprawling, almost three-hour crime drama, it was hailed by many critics as Mann's most ambitious study of his traditional milieu to date. Despite some high-powered set pieces (an intense shoot-out on a busy New York City avenue is a particular stand-out), the film, by contrast to many other Mann crime dramas, is turgid and melodramatic in its overall effect, capped by an ending that resolves the plot not with a bang but a whimper.

Not so Mann's next film, The Insider , wherein the director cast his eye not on street crime again but on corporate crime. The film is based on the true story of Jeffrey Wigand (Russell Crowe), a former researcher and executive for the Brown & Williamson tobacco company who blows the whistle on the industry's awareness of the addictiveness of cigarettes—and covert research to increase that addictiveness (which Wigand took part in)—to 60 Minutes producer Lowell Bergman (Al Pacino). Typical of many Mann heroes, Wigand exposes this public health issue in part to regain his self-respect, an act that comes at great personal cost to him when 60 Minutes bows to pressure from Big Tobacco as well as its own corporate interests, shelves the interview, and Wigand's life and career crumble as he's hung out to dry—until the truth finally comes out in the print press. Mann was rewarded for this rich and compelling docudrama—which unlike most big-budget Hollywood product of recent times has more on its mind than just a hat—with the best reviews of his career. Neither the tobacco industry nor 60 Minutes were among those lavishing kudos, however.

—John McCarty

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: