Gordon Parks - Director

Nationality: American. Born: Fort Scott, Kansas, 30 November 1912. Education: Attended high school in St. Paul, Minnesota. Family: Married 1) Sally Alvis, 1933 (divorced 1961); 2) Elizabeth Campbell, December, 1962 (divorced 1973); 3) Genevieve Young (a book editor), August 26, 1973; children: (first marriage) Gordon, Jr. (deceased), Toni (Mrs. Jean-Luc Brouillaud), David; (second marriage) Leslie. Career: Worked at various jobs prior to 1937; freelance fashion photographer in Minneapolis, 1937–42; photographer with Farm Security Administration, 1942–43, with Office of War Information, 1944, and with Standard Oil Company of New

Films as Director:

- 1969

-

The Learning Tree (+ mus, pr, sc)

- 1971

-

Shaft

- 1972

-

Shaft's Big Score! (+ mus)

- 1974

-

The Super Cops

- 1976

-

Leadbelly

- 1984

-

Solomon Northrup's Odyssey ( Half-Slave,Half-Free )(—for TV)

Films as Actor:

- 1992

-

Lincoln (Kunhardt—for TV) (voice of Henry H. Garnet)

- 2000

-

Shaft (Singleton) (as Lenox Lounge Patron)

Publications

By PARKS: books—

Flash Photography , New York, 1947.

Camera Portraits: The Techniques and Principles of Documentary Portraiture , New York, 1948.

The Learning Tree , New York, 1963.

A Choice of Weapons (autobiography), New York, 1966.

A Poet and His Camera (poems), self-illustrated with photographs, New York, 1968.

Gordon Parks: Whispers of Intimate Things (poems), self-illustrated with photographs, New York, 1971.

Born Black (essays), self-illustrated with photographs, Philadelphia, 1971.

In Love (poems), self-illustrated with photographs, New York, 1971.

Moments without Proper Names (poems), self-illustrated with

photographs, New York, 1975.

Flavio , New York, 1978.

To Smile in Autumn: A Memoir , New York, 1979.

Shannon (novel), Boston, 1981.

Voices in the Mirror: An Autobiography , New York, 1990.

Author of foreword, Harlem: Photographs by Aaron Siskind, 1932–1940 , edited by Ann Banks, Washington D.C., 1991.

Author of introduction, Soul Unsold , by Mandy Vahabzadeh, Marina del Rey, California, 1992.

Author of introduction, A Ming Breakfast: Grits and Scrambled Moments , New York, 1992.

Arias in Silence , Boston, 1994.

Contributor, In the Alleys: Kids in the Shadow of the Capitol , Washington D.C., 1995.

Glimpses toward Infinity , Boston, 1996.

Contributor, Spirited Minds , Minneapolis, 1996.

A Star for Noon , Boston, 2000.

Contributor, Autobiography of a People: Three Centuries of African-American History Told by Those Who Lived It , edited by Herb Boyd, New York, 2000.

On PARKS: books—

Rolansky, John D., editor, Creativity , New York, 1970.

Turk, Midge, Gordon Parks , New York, 1971.

Harnan, Terry, Gordon Parks: Black Photographer and Film Maker , London, 1972.

Monaco, James, American Film Now: The People, the Power, the Money, the Movies , New York,1979.

Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 33: Afro-American Fiction Writers after 1955 , Detroit, 1984.

Bogle, Donald, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies & Bucks: A History of Blacks in American Films from Birth of a Nation to Malcolm X , New York, 1994.

Parks, Gordon, Jr. Half Past Autumn: A Retrospective , Boston, 1998.

Martinzez, Gerald, Diana Martinzez, and Andres Chavez, What It Is, What It Was! , New York, 1998.

On PARKS: articles—

America , 24 July 1971.

American Photo , September-October 1991.

American Visions , December 1989, February 1991, and February-March 1993.

Best Sellers , 1 April 1971.

Black Enterprise , January 1992.

Black World , August 1973.

Commonweal , 5 September 1969.

Cue , 9 August 1969.

Ebony , July 1946.

Films and Filming , April 1972 and October 1972.

Films in Review , October 1972.

Focus on Film , October 1971.

Journal of American History , December 1987.

Life , October 1994 and February 1996.

Newsweek , 29 April 1968, 11 August 1969, 17 July 1972, and 19 April 1976.

New Yorker , 2 November 1963 and 13 February 1966.

New York Times , 4 October 1975, 3 December 1975, and 1 March 1986.

New York Times Book Review , 15 September 1963, 13 February 1966, 23 December 1979, 9 December 1990, and 1 March 1996.

Point of View , Winter 1998.

PSA (Photographic Society of America) Journal , November 1992.

San Jose Mercury News , 23 February 1990.

Saturday Review , 12 February 1966 and 9 August 1969.

Show Business , 2 August 1969.

Smithsonian , April 1989.

Time , 6 September 1963, 29 September 1969, 24 May 1976, and 26 June 2000.

Variety , 6 November 1968 and 25 June 1969.

Vogue , 1 October 1968 and January 1976.

Washington Post , 20 October 1978 and 24 January 1980.

* * *

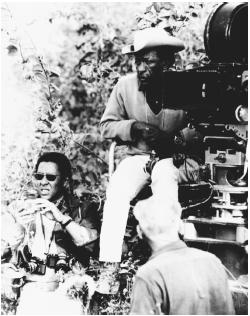

Already an award-winning photographer and novelist, Gordon Parks beat out Melvin Van Peebles by a few months to become, in 1969, the first African American hired to direct a major studio production. Parks had his Kansas-set The Learning Tree under way at Warner Bros. when Van Peebles was tapped to do the satire Watermelon Man for Columbia Pictures. As the trajectory of both men's careers would later make clear, Parks' historic role had more to do with versatility and fortitude than timing or blind luck. One need only compare the directors' follow-up projects—Parks went on to do the trend-setting Shaft for MGM; Van Peebles made the incendiary, X-rated Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song —to understand why Hollywood was more comfortable casting Parks as civil rights standard bearer. Professorial in demeanor (with ever-present pipe, ascot, and natty sports jacket), Parks, one could argue, was less threatening to a power structure more interested in salving its conscience and tapping into a new urban market than in advancing the cause of blacks in Hollywood.

Was Parks then establishment Hollywood's token black director, a "sell-out," in the parlance of the day? This has been a subject of some debate by, among others, Van Peebles (who charges yes) and Parks (who resents the implication, pointing to the large number of blacks employed on his films). To answer in the affirmative is in no way to diminish Parks importance to the erratic, snail-paced integration of the studio system. Someone had to be first, and that role fell to Parks more as an outgrowth of his deep-rooted humanism than as a result of any filmmaking skills. Indeed, Parks learned as he went on the set of The Learning Tree. The son of a Fort Scott, Kansas, sharecropper, Parks, the youngest of 15 children, bounced among menial jobs until, at age 25, he found his niche: still photography. He would go on to break color barriers in the worlds of fashion photography and photo-journalism, first with Vogue and then with Life magazine. Among Parks' most famous portraitures were studies of Langston Hughes, Duke Ellington, and Ingrid Bergman. As photojournalist, he chronicled the lives of a Harlem gang member, a Washington, D.C., cleaning woman named Ella Watson, and a Brazilian street orphan named Flavio. The Life studies—bracing, accusatory, always empathetic—brought accolades and retrospectives. In 1963, Parks added an autobiographical novel to his already-standard works on portrait and documentary photography. The Learning Tree , set in Cherokee Flats, Kansas, in the 1920s, is at once nostalgic, heartbreaking, and richly layered. The protagonist, a 12-year-old named Newt, comes of age as he witnesses acts of violence and betrayal from both blacks and whites. Newt's mother offers a metaphoric lesson: "Some of the people are good and some of them are bad—just like the fruit on a tree . . . No matter if you go or stay, think of Cherokee Flats like that till the day you die—let it be your learnin' tree."

Likened to stories of Faulkner and Steinbeck, and quickly added to required reading lists, The Learning Tree was immediately sought by Hollywood. Taking a page from silent-movie pioneer Oscar Micheaux, who produced and directed movies from his own books, Parks said he would only option the novel with himself attached as producer, director, screenwriter, and composer. In 1968, Warner Bros. agreed, and Parks, at age 56, returned to Fort Scott, Kansas, to shoot his first film, an at-times jarring blend of soft-focus sentimentality and bitter life lessons. Generally dismissed by critics expecting a harsher indictment of the System, The Learning Tree (1969) found vindication in 1989, when it become, along with Citizen Kane and Casablanca , one of the first "landmark" films selected by the Library of Congress's National Film Registry.

Shaft (1971), Parks' second feature, could not have been more of a departure. It starred Richard Roundtree as a Greenwich Village private eye—"the cat that won't cop out when there's danger all about"—who's caught between black militants, racist cops, and warring racketeers. The character (created by novelist Ernest Tidyman) remains, according to Time magazine, "one of the first black movie heroes to talk back to the Man and get away with it." Produced for $1 million, it grossed over $12 million and, with Van Peebles' Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song , ushered in the short-lived blaxploitation craze. An Oscar-winner (for Isaac Hayes' theme song), Shaft far outdistanced the black-themed (and predominantly white-produced) action pictures to come by walking the line between crass exploitation and stinging indictment of urban racism, in its many permutations.

In 1972—the year his son, Gordon Parks Jr., directed and starred in Superfly (1972)—Parks Sr. directed and composed the music for Shaft's Big Score (1972), a slicker, less successful sequel that climaxed in a 16-minutes, air-sea-land chase a la countless James Bond capers. Instead of doing the third Shaft ( Shaft in Africa ), Parks became the first black director to do a non-black-themed studio picture: The Super Cops (1974), starring Ron Liebman and David Selby as undercover narcs who, like Mel Gibson and Danny Glover in the "Lethal Weapon" movies, bend the law to exact street justice. Many critics consider Super Cops Parks' best film.

In his sixties, Parks changed gears yet again to do a period biopic of blues-folk singer Huddie Ledbetter titled Leadbelly (1976). Roger E. Mosley played Ledbetter, a gifted 12-string guitarist who drifts in and out of prison as he's told, "It's gonna cost you to play the blues." Though it received favorable reviews—and remains Parks' favorite film — Leadbelly failed to find wide release and Parks' cachet as trailblazer continued to erode. In the 1980s, he turned to public television (doing the music and libretto for a PBS ballet based on Martin Luther King Jr.'s life) and had to content himself with the role of unofficial technical adviser on Steven Spielberg's The Color Purple and other prestige race films overseen by whites. In 1990, upon receiving the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame's Paul Robeson Award, Parks said, "I found myself thinking, 'I could direct this film ( The Color Purple ).' And looking back, I'm sure certain black directors could have brought a hell of a lot more sensitivity to certain 'white' movies about blacks." Little has changed in Hollywood since the early 1970s, he charges. "There's still a tremendous amount of discrimination and prejudice, and a lot of black talent continues to be wasted. . . . Getting money from white-run studios is still the problem. They still pay us a lot of lip service, but that's all."

Though he continues to write and collect honorary degrees, Parks' role in the integration of Hollywood has been all but forgotten. Critics generally disparage his studio films, which, like some of his best-known photographs, combine social awareness with a vulgarian's love of glitz and excess. In the 1990s, Parks was discovered by the new generation of black filmmakers anxious to seek his advice and validation. Boyz N the Hood director John Singleton called Shaft "a benchmark in American film" and added, "I think I'm walking in the path of Gordon Parks more than anybody." In 2000, Singleton put his own less-political spin on Shaft by casting Samuel L. Jackson as John Shaft's even more stylish and volatile nephew, now a member of the NYPD. Parks, still sporting a pipe and walrus mustache, can be seen in a Harlem lounge cameo.

—Glenn Lovell

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: