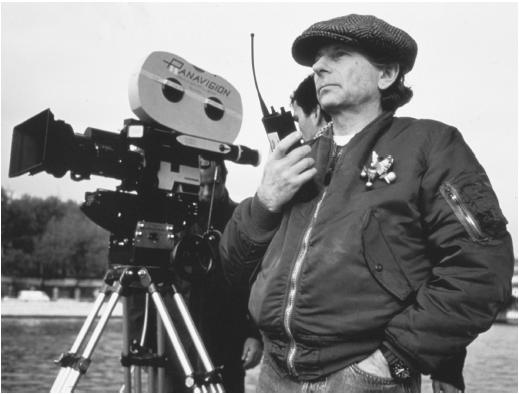

Roman Polanski - Director

Nationality: Polish. Born: Paris, 18 August 1933. Education: Krakow Liceum Sztuk Plastycznych (art school), 1950–53; State Film School, Lodz, 1954–59. Family: Married 1) actress Barbara Kwiatkowska, 1959 (divorced 1961); 2) actress Sharon Tate, 1968 (died 1969); 3) actress Emmanuelle Seigner, 1989. Career: Returned to Poland, 1936; actor on radio and in theatre, from 1945, and in films, from 1951; joined filmmaking group KAMERA as assistant to Andrzej Munk, 1959; directed first feature, Knife in the Water , 1962, denounced by Polish Communist Party chief Gomulka, funding for subsequent films denied, moved to Paris, 1963; moved to London, 1964, then to Los Angeles, 1968; wife Sharon Tate and three friends murdered in Bel Air, California, home by members of Charles Manson cult, 1969; opera director, from 1974; convicted by his own plea of unlawful sexual intercourse in California, 1977; committed to a diagnostic facility, Department of Correction; upon completion of study, returned to Paris; also stage actor and director. Awards: Silver Bear, Berlin Film Festival, for Repulsion , 1965; Golden Bear, Berlin Festival, for Cul-de-Sac , 1966; César Award, for Tess , 1980. Address: Lives in Paris.

Films as Director and Scriptwriter:

- 1955/57

-

Rower ( The Bike ) (short)

- 1957/58

-

Morderstwo ( The Crime ) (short)

- 1958

-

Rozbijemy zabawe ( Break up the Dance ) (short); Dwaj ludzie z szasa ( Two Men and a Wardrobe ) (short) (+ role)

- 1959

-

Gdy spadaja anioly ( When Angels Fall ) (short) (+ role as old woman)

- 1961

-

Le Gros et le maigre ( The Fat Man and the Thin Man ) (short) (co-sc, + role as servant)

- 1962

-

Ssaki ( Mammals ) (short) (co-sc, + role); Nóz w wodzie ( Knife in the Water ) (co-sc)

- 1963

-

"La Rivière de diamants" ("A River of Diamonds") episode of Les Plus Belles Escroqueries du monde ( The Most Beautiful Swindles in the World ) (co-sc)

- 1964

-

Repulsion (co-sc)

- 1965

-

Cul-de-sac (co-sc)

- 1967

-

The Fearless Vampire Killers ( Pardon Me, but Your Teeth Are in My Neck ; Dance of the Vampires ) (co-sc, + role as Alfred)

- 1968

-

Rosemary's Baby

- 1972

-

Macbeth (co-sc)

- 1973

-

What? ( Che? ; Diary of Forbidden Dreams ) (co-sc, + role as Mosquito)

- 1974

-

Chinatown (d only, + role as man with knife)

- 1976

-

Le Locataire ( The Tenant ) (co-sc, + role as Trelkovsky)

- 1979

-

Tess (co-sc)

- 1985

-

Pirates (co-sc)

- 1988

-

Frantic (co-sc)

- 1992

-

Bitter Moon (co-sc,pr)

- 1993

-

Death and the Maiden

- 1999

-

The Ninth Gate (co-sc, pr)

- 2001

-

The Pianist (+ co-sc, pr)

Other Films:

- 1953

-

Trzy opowiesci ( Three Stories ) (Nalecki, Poleska, Petelski) (role as Maly)

- 1954

-

Pokolenie ( A Generation ) (Wajda) (role as Mundek)

- 1955

-

Zaczárowany rower ( The Enchanted Bicycle ) (Sternfeld) (role as Adas)

- 1956

-

Koniec wojny ( End of the Night ) (Dziedzina, Komorowski, Uszycka) (role as Maly)

- 1957

-

Wraki ( Wrecks ) (Petelski) (role)

- 1958

-

Zadzwoncie do mojej zony ( Phone My Wife ) (Mach) (role)

- 1959

-

Lotna (Wajda) (role as bandsman)

- 1960

-

Niewinni czarodzieje ( Innocent Sorcerors ) (Wajda) (role as Dudzio); Ostroznie yeti ( The Abominable Snowman ) (Czekalski) (role); Do Widzenia do Jutra ( See You Tomorrow ) (Morgenstern) (role as Romek); Zezowate szczescie ( Bad Luck ) (Munk) (role)

- 1964

-

Do You Like Women? (Léon) (co-sc)

- 1968

-

The Woman Opposite (Simon) (co-sc)

- 1969

-

A Day at the Beach (Hessera) (pr); The Magic Christian (McGrath) (role)

- 1972

-

Weekend of a Champion (Simon) (pr, role as interviewer)

- 1974

-

Blood for Dracula (Morrissey) (role as a villager)

- 1991

-

Back in the USSR (Serafian) (role as Kurilov)

- 1994

-

Gross Fatigue (role as himself)

- 1995

-

A Simple Formality (role as Inspector)

- 2000

-

Ljuset häller mig sällskap ( Light Keeps Me Company ) (Nykvist) (role as himself); Hommage à Alfred Lepetit ( Tribute to Alfred Lepetit ) (Rousselot) (role)

Publications

By POLANSKI: books—

What? , New York, 1973.

Three Films , London, 1975.

Roman (autobiography), London, 1984.

Polanski par Polanski , edited by Pierre-André Boutang, Paris, 1986.

By POLANSKI: articles—

Interview with Gretchen Weinberg, in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1963/64.

"Landscape of a Mind: Interview with Roman Polanski," with Michel Delahaye and Jean-André Fieschi, in Cahiers du Cinéma in English (New York), February 1966.

Interview with Michel Delahaye and Jean Narboni, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), January 1968.

"Polanski in New York," an interview with Harrison Engle, in Film Comment (New York), Fall 1968.

Interview with Joel Reisner and Bruce Kane, in Cinema (Los Angeles), vol. 5, no. 2, 1969.

"Satisfaction: A Most Unpleasant Feeling," an interview with Gordon Gow, in Films and Filming (London), April 1969.

Interview, in The Film Director as Superstar , by Joseph Gelmis, Garden City, New York, 1970.

"Playboy Interview: Roman Polanski," with Larry DuBois, in Playboy (Chicago), December 1971.

"Andy Warhol Tapes Roman Polanski," in Inter/View (New York), November 1973.

"Dialogue on Film: Roman Polanski," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), August 1974.

"Roman Polanski on Acting," with D. Brandes, in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), January 1977.

" Tess ," an interview with Serge Daney and others, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), December 1979.

Interview with P. Pawlikowski and L. Kolodziejczyk, in Stills (London), April/May 1984.

Interview with O. Darmon, in Cinématographe (Paris), May 1986.

"Roman Oratory," an interview with Andrea R. Vaucher, in American Film , April 1991.

"At the Point of No Return," an interview with Rider McDowell, in California , August 1991.

"Entretien avec Roman Polanski," with A. de Baecque and T. Jousse, in Cahiers du Cinéma , May 1992.

"Roman Polanski's Bitter Moon ," an interview with Stephen O'Shea, in Interview , March 1994.

"From Knife to Death with Roman Polanski," an interview with Tomm Carroll, in DGA Magazine (Los Angeles), December-January 1994–1995.

Interview with Catherine Axelrad and Laurent Vachaud, in Positif (Paris), April 1995.

"I Make Films for Adults: Death and the Maiden ," an interview with David Thompson and Nick James, in Sight and Sound (London), April 1995.

" Death and the Maiden: Trial by Candlelight," an interview with Stephen Pizzello, in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), April 1995.

"Polanski: En studie I skräck (och hämnd)," an interview with Anneli Bojstad, in Chaplin (Stockholm), vol. 37, no. 2, 1995.

"The Most Popular Illusionists in the World," in Interview , January 1996.

"Letters: [I Am Writing You This Letter?]," in Vanity Fair (New York), July 1997.

On POLANSKI: books—

Butler, Ivan, The Cinema of Roman Polanski , New York, 1970.

Kane, Pascal, Roman Polanski , Paris, 1970.

Belmans, Jacques, Roman Polanski , Paris, 1971.

Bisplinghoff, Gretchen, and Virginia Wexman, Roman Polanski: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1979.

Kiernan, Thomas, The Roman Polanski Story , New York, 1980.

Leaming, Barbara, Polanski: The Filmmaker as Voyeur: A Biography , New York, 1981; also published as Polanski: His Life and Films , London, 1982.

Paul, David W., Politics, Art, and Commitment in the Eastern European Cinema , New York, 1983.

Dokumentation: Polanski und Skolimowski: Das absurde im film , Zurich, 1985.

Wexman, Virginia Wright, Roman Polanski , Boston, 1985.

Jacobsen, Wolfgang, and others, Roman Polanski , Munich, 1986.

Avron, Dominique, Roman Polanski , Paris, 1987.

McCarty, John, The Modern Horror Film, Secaucus, New Jersey, 1990.

Preljocaj, Angelin, Roman Polanski , Paris, 1992.

McCarty, John, Movie Psychos and Madmen , Secaucus, New Jersey, 1993.

McCarty, John, The Fearmakers , New York, 1994.

Goulding, Daniel J., ed., Five Filmmakers: Tarkovsky, Forman, Polanski, Szabo, Makavejev , Bloomington, 1994.

On POLANSKI: articles—

Haudiquet, Philippe, "Roman Polanski," in Image et Son (Paris), February/March 1964.

Brach, Gérard, "Polanski via Brach," in Cinéma (Paris), no. 93, 1965.

McArthur, Colin, "Polanski," in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1968.

McCarty, John, "The Polanski Puzzle," in Take One (Montreal), May/June 1969.

Tynan, Kenneth, "Polish Imposition," in Esquire (New York), September 1971.

"Le Bal des vampires," special Polanski issue of Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), January 1975.

Leach, J., "Notes on Polanski's Cinema of Cruelty," in Wide Angle (Athens, Ohio), vol. 2, no. 1, 1978.

Kennedy, H., " Tess : Polanski in Hardy Country," in American Film (Washington, D.C.), October 1979.

"L'Univers de Roman Polanski," special section, in Cinéma (Paris), February 1980.

Sinyard, Neil, "Roman Polanski," in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), November/December 1981.

Polanski Section of Kino (Warsaw), July 1986.

Polanski Section of Positif (Paris), May 1988.

Sutton, M., "Polanski in Profile," in Films and Filming (London), September 1988.

Ansen, David, "The Man Who Got Away," in Newsweek , 28 March 1994.

Weschler, Lawrence, "Artist in Exile," in New Yorker , 5 December 1994.

Davis, Ivor, "Out of Exile?" in Los Angeles Magazine , January 1995.

Heilpern, John, "Roman's Tortured Holiday," in Vanity Fair , January 1995.

Aitio, Tommi, "Puolalainen Hollywoodissa," in Filmihullu (Helsinki), no. 3, 1997.

Robinson, J., "Polanski's Inferno," in Vanity Fair (New York), April 1997.

Epstein, J., "Bertolucci Leads a Star-studded Panel on Cinematic Investigation," in Cinema Papers (Fitzroy), August 1997.

Leitch, Thomas M., "The Hitchcock Moment," in Hitchcock Annual (Gambier), 1997–1998.

Fierz, Charles L., "Polanski Misses: Polanski's Reading of Hardy's Tess ," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury), April 1999.

* * *

As a student at the Polish State Film School and later as a director working under government sponsorship, Roman Polanski learned to make films with few resources. Using only a few trained actors (there are but three characters in his first feature) and a hand-held camera (due to the unavailability of sophisticated equipment) Polanski managed to create several films which contributed to the international reputation of the burgeoning Polish cinema.

These same limitations contributed to the development of a visual style which was well suited to the director's perspective on modern life: one which emphasized the sort of precarious, unstable world suggested by a hand-held camera, and the sense of isolation or removal from a larger society which follows the use of only small groupings of characters. In fact, Polanski's work might be seen as an attempt to map out the precise relationship between the contemporary world's instability and tendency to violence and the individual's increasing inability to overcome his isolation and locate some realm of meaning or value beyond himself.

What makes this concern with the individual and his psyche especially remarkable is Polanski's cultural background. As a product of a socialist state and its official film school at Lodz, he was expected to use his filmmaking skills to advance the appropriate social consciousness and ideology sanctioned by the government. However, Polanski's first feature, Knife in the Water , drew the ire of the Communist Party and was denounced at the Party Congress in 1964 for showing the negative aspects of Polish life. Although less an ideological statement than an examination of the various ways in which individual desires and powers determine our lives, Knife in the Water and the response it received seem to have precipitated Polanski's subsequent development into a truly international filmmaker. In a career that has taken him to France, England, Italy, and the United States in search of opportunities to write, direct, and act, he has consistently shown more interest in holding up a mirror to the individual impulses, unconscious urges, and the personal psychoses of human life than in dissecting the different social and political forces he has observed.

The various landscapes and geographies of Polanski's films certainly seem designed to enhance this focus, for they pointedly remove his characters from most of the normal structures of social life as well as from other people. The boat at sea in Knife in the Water , the oppressive flat and adjoining convent in Repulsion , the isolated castle and flooded causeway of Cul-de-sac , the prison-like apartments of Rosemary's Baby and The Tenant , and the empty fields and deserted manor house in Tess form a geography of isolation that is often symbolically transformed into a geography of the mind, haunted by doubts, fears, desires, or even madness. The very titles of films like Cul-de-sac and Chinatown are especially telling in this regard, for they point to the essential strangeness and isolation of Polanski's locales, as well as to the sense of alienation and entrapment which consequently afflicts his characters. Brought to such strange and oppressive environments by the conditions of their culture ( Chinatown ), their own misunderstood urges ( Repulsion ), or some inexplicable fate ( Macbeth ), Polanski's protagonists struggle to make the unnatural seem natural, to turn entrapment into an abode, although the result is typically tragic, as in the case of Macbeth , or absurd, as in Cul-de-sac. Such situations have prompted numerous comparisons, especially of Polanski's early films, to the absurdist dramas of Samuel Beckett. As in many of Beckett's plays, language and its inadequacy play a significant role in Polanski's works, usually forming a commentary on the absence or failure of communication in modern society. The dramatic use of silence in Knife in the Water actually "speaks" more eloquently than much of the film's dialogue of the tensions and desires which drive its characters and operate just beneath the personalities they try to project. In the conversational clichés and banality which mark much of the dialogue in Cul-de-sac , we can discern how language often serves to cloak rather than communicate meaning. The problem, as the director most clearly shows in Chinatown , is that language often simply proves inadequate for capturing and conveying the complex and enigmatic nature of the human situation. Detective Jake Gittes's consternation when Evelyn Mulwray tries to explain that the girl he has been seeking is both her daughter and her sister—the result of an incestuous affair with her father—points out this linguistic inadequacy for communicating the most discomfiting truths. It is a point driven home at the film's end when, after Mrs. Mulwray is killed, Gittes is advised not to try to "say anything." His inability to articulate the horrors he has witnessed ultimately translates into the symptomatic lapse into silence also exhibited by the protagonists of The Tenant and Tess , as they find themselves increasingly bewildered by the powerful driving forces of their own psyches and the worlds they inhabit.

Prompting this tendency to silence, and often cloaked by a proclivity for a banal language, is a disturbing force of violence which all of Polanski's films seek to analyze—and for which they have frequently been criticized. Certainly, his own life has brought him all too close to this most disturbing impulse, for when he was only eight years old Polanski and his parents were interned in a German concentration camp where his mother died. In 1969 his wife Sharon Tate and several friends were brutally murdered by Charles Manson's followers. The cataclysmic violence in the decidedly bloody adaptation of Macbeth , which closely followed his wife's death, can be traced through all of the director's features, as Polanski has repeatedly tried to depict the various ways in which violence erupts from the human personality, and to confront in this specter the problem of evil in the world.

The basic event of Rosemary's Baby —Rosemary's bearing the offspring of the devil, a baby whom she fears yet, because of the natural love of a mother for her own child, nurtures—might be seen as a paradigm of Polanski's vision of evil and its operation in our world. Typically, it is the innocent or unsuspecting individual, even one with the best of intentions, who unwittingly gives birth to and spreads the very evil or violence he most fears. The protagonist of The Fearless Vampire Killers , for example, sets about destroying the local vampire and saving his beloved from its unnatural hold. In the process, however, he himself becomes a vampire's prey and, as a concluding voice-over solemnly intones, assists in spreading this curse throughout the world.

It is a somber conclusion for a comedy, but a telling indication of the complex tone and perspective which mark Polanski's films. He is able to assume an ironic, even highly comic attitude towards the ultimate and, as he sees it, inevitable human problem—an abiding violence and evil nurtured even as we individually struggle against these forces. The absurdist stance of Polanski's short films, especially Two Men and a Wardrobe and The Fat and the Lean , represents one logical response to this paradox. That his narratives have grown richer, more complicated, and also more discomfiting in their examination of this situation attests to Polanski's ultimate commitment to understanding the human predicament and to rendering articulate that which seems to defy articulation. From his own isolated position—as a man effectively without a country—Polanski tries to confront the problems of isolation, violence, and evil, and to speak of them for an audience prone to their sway.

After a highly publicized 1977 sex scandal resulted in his flight from the United States and subsequent exile, Polanski surprised many by doing an apparent about face in terms of subject matter, and creating one of his most restrained and visually beautiful films: the aforementioned Tess. It was based on the classic Thomas Hardy novel of innocence destroyed, Tess of the D'Urbervilles. Polanski dedicated the movie to the memory of his murdered wife, Sharon Tate. Tess was followed by Pirates , a parody of the swashbuckling adventure films starring Errol Flynn that Polanski had enjoyed as a youth. Walter Matthau starred in the film as the comically villainous Captain Red, a role Polanski had written for Jack Nicholson. When Pirates failed at the box-office, Polanski returned to the cinema of fear with Frantic , a Hitchcock-style thriller with a Polanski touch, starring Harrison Ford. The story of a man inadvertently trapped in a nightmare situation in a foreign land, Frantic drew upon many of Polanski's favorite themes. But as a bid for critical and commercial success, it failed to repeat the performance of his earlier fear-films. The master of psychological suspense was not to be counted out yet, though. In 1992, Polanski bounced back with the film his fans had been clamoring for for years—a potent and powerful synthesis of all the absurdist comedies, parodies, thrillers, fear-films, and detective yarns Polanski had made in the past: Bitter Moon. He followed it up with the taut and well-reviewed but only modestly successful Death and the Maiden. Roman Polanski's importance as a filmmaker hinges upon a uniquely unsettling point of view. All his characters try continually, however clumsily, to connect with other human beings, to break out of their isolation and to free themselves of their alienation. Could it be that his nightmarish films serve much the same purpose? Perhaps they too are the continuing efforts of a terrified young Jewish boy, adrift in a war-torn land, to connect with the rest of humanity—even after all these years.

—J. P. Telotte, updated by John McCarty

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: