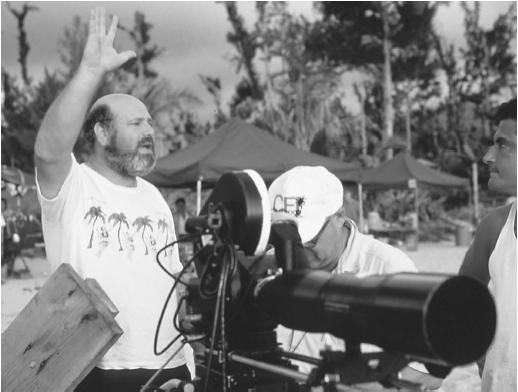

Rob Reiner - Director

Nationality: American. Born: 6 March 1945. Education: Attended University of California, Los Angeles. Family: Son of actor/director Carl Reiner; married 1) actress/director Penny Marshall, 1971 (divorced); 2) Michele Singer, 1989. Career: Worked as actor and improvisational comedian beginning in 1965; worked as comedy writer for television variety shows, 1968; played key role of Michael Stivic in television series All in the Family , 1971–1978; appeared in wide variety of television comedy as guest performer throughout 1970s and 1980s; directed first film, This Is Spinal Tap , 1984; directed breakthrough film, Stand by Me , 1986; co-founded Castle Rock Entertainment. Awards: Emmy awards for Best Supporting Actor, 1974 and 1978, for All in the Family. Agent: Jane Sindell, Creative Artists Agency, 9830 Wilshire Boulevard, Beverly Hills, California 90212, U.S.A. Address: Castle Rock Entertainment, 335 N. Maple Drive, Suite 135, Beverly Hills, California 90210–3867, U.S.A.

Films as Director:

- 1984

-

This Is Spinal Tap (+ co-sc, co-songs, role)

- 1985

-

The Sure Thing

- 1986

-

Stand by Me

- 1987

-

The Princess Bride (+ co-pr)

- 1989

-

When Harry Met Sally (+ co-pr)

- 1990

-

Misery (+ co-pr)

- 1992

-

A Few Good Men

- 1995

-

North (+ pr); The American President (+ pr)

- 1996

-

The Ghosts of Mississippi

- 1997

-

I Am Your Child (for TV)

- 1999

-

The Story of Us (role)

Films as Actor:

- 1967

-

Enter Laughing (Carl Reiner) (as Clark Baxter)

- 1970

-

Halls of Anger (Paul Bogart) (as Leaky Couloris); Where's Poppa (Carl Reiner) (as Roger)

- 1971

-

Summertree (Anthony Newly) (as Don)

- 1974

-

Thursday's Game (James L. Brooks) (for TV)

- 1975

-

How Come Nobody's on Our Side (Richard Michaels) (as Miguelito)

- 1977

-

Fire Sale (Alan Arkin) (as Russel Fikus)

- 1979

-

More than Friends (Jim Burrows) (for TV) (+ co-sc, co-exec pr)

- 1982

-

Million Dollar Infield (Hal Cooper) (for TV) (+ co-sc, co-pr)

- 1987

-

Throw Momma from the Train (Danny DeVito) (as Joel)

- 1990

-

Postcards from the Edge (Mike Nichols) (as Joe Pierce); Likely Stories, Volume 1 (comedy sketches for cable TV)

- 1991

-

Regarding Henry (Mike Nichols)

- 1993

-

Sleepless in Seattle (Nora Ephron) (as Jay)

- 1994

-

Bullets over Broadway (Woody Allen) (as Sheldon Flender); Mixed Nuts (as Dr. Kinsky)

- 1995

-

Bye Bye, Love (S. Weisman) (as Dr. Townsend)

- 1996

-

Mad Dog Time (Bishop) (as Albert the Chauffeur); For Better or Worse (Alexander) (as Dr. Plosner); The First Wives Club (Hugh Wilson) (as Dr. Packman)

- 1998

-

Primary Colors (Nichols) (as Izzy Rosenblatt)

- 1999

-

Ed TV (Howard) (as Whitaker); The Muse (Brooks) (as himself)

Publications

By REINER: articles—

"Prince Rob," an interview with Harlan Jacobson, in Film Comment , September 1987.

"Reiner's Reason," an interview with April Bernard, in Interview , July 1989.

"L'homme qui racontait des histoires," an interview with I. Katsahnias, in Cahiers du Cinéma , October 1989.

"Rob Reiner on Stephen King," an interview with G. Wood, in Cinefantastique , no. 4, 1991.

"Entretiens avec Rob Reiner et William Goldman," an interview with I. Katsahnias, in Cahiers du Cinéma , no. 4, 1991.

"Rob Reiner Makes a Comedy of Youthful Manners," an interview with R. Alexander, in New York Times , 24 February 1985.

Interview with D. Rosenthal, in Playboy , July 1985.

"Les fictions fatales," an interview with Iannis Katsahnias, in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), October 1989.

"Reiner Reason," an interview with Nigel Floyd, in Time Out (London), 1 May 1991.

" The American President ," in Premiere (Boulder), December 1995.

"Ghosts of Past and Present," an interview with G. Fuller, in Interview , January 1997.

On REINER: book—

Dunne, Michael, "Jim Henson and Rob Reiner: Kermit's Dad Meets Rob Petrie's Son," in Metapop: Self-Referentiality in Contemporary American Popular Culture , University Press of Mississippi, 1992.

On REINER: articles—

Harmetz, A., "Reiner Has Last Laugh with His Rock Spoof," in New York Times , 25 April 1984.

Kilday, Gregg, "Rob Reiner Grows Up," in Vanity Fair , July 1989.

Lloyd, Robert, "Pals," American Film , July/August 1989.

Weber, B., "Can Men and Women Be Friends?" in New York Times , 9 July 1989.

Gray, M., "Love Story," in Films and Filming , December 1989.

Katsahnias, I., "Les fictions fatales," in Cahiers du Cinéma , Octo-ber 1989.

Sharkey, B., "Misery's Company Loves a Good Time," in New York Times , 17 June 1990.

Valot, J., "Rob Reiner," in Revue du Cinema , September 1990.

Bernard, Rita, "From Screwballs to Cheeseballs: Comic Narrative and Ideology in Capra and Reiner," in New Orleans Review , no. 3, 1990.

Kermode, Mark, "Misery," in Sight and Sound , May 1991.

Silveman, J., "Rob Reiner's Latest Hat Trick," in New York Times , 21 July 1991.

Stefancic, M., Jr., "Rob Reiner," in Ekran , no. 3, 1991.

Goldman, Steven, "Masters of the Numbers Game," in Guardian , 2 January 1993.

Biskind, Peter, "A Few Good Menshes," in Premiere , January 1993.

Newman, Kim, "A Few Good Men," in Sight and Sound , January 1993.

Bruzzi, Stella, "Court Etiquette," in Sight and Sound , February 1993.

Rhodes, Joe, "On Comedy, Books, and Toupees," in Los Angeles Times , 16 June 1993.

Meisel, M., "Friends and Partners Mine Success at Castle Rock," in Film Journal (New York), November/December 1995.

Kelleher, E., "Justice Affirmed," in Film Journal (New York), December 1996.

Ansen, D., "Twister Impossible: The Movie as E-ticket Ride," in Written By. Journal: The Writers Guild of America, West (Los Angeles), July 1997.

* * *

Rob Reiner is a show business kid who has learned much from his famous father, Carl Reiner, creator of the American television series The Dick Van Dyke Show and director of many comedy films—most notably Where's Poppa and The Jerk. Beginning his career as an actor, Rob Reiner's most notable role was as Michael Stivic in the long-running American television series All in the Family. Michael Stivic was the not-too-bright comic foil for his right-wing, racist father-in-law, Archie Bunker. Thus, from the beginning of Reiner's career, several elements become apparent that are important to his development as a director: 1) a profound sympathy for the actor and the concomitant empathy to elicit skillful performances; 2) a deep understanding of comedy and satire and, more generally, an innate feel for timing and structure; and 3) an inherently liberal, humanistic sensibility.

If Reiner's facility as a comic gives him great abilities of observation, its negative side is that his career has been by and large a series of very skillful imitations of other directors and other styles. In this context, it is hard to think of Reiner as a major Hollywood artist, no matter how successful his films. Indeed, Reiner would have made an extraordinary director at the heyday of the studio system, taking on the A-assignments with dazzling ability. So if Reiner has not yet demonstrated himself to be an auteur —like Woody Allen, with whom he has been compared, or like David Lynch, who seems a polar opposite—he is definitely a metteur en scene , like Sydney Lumet, Norman Jewison, or Sydney Pollack. Reiner's first film was a mock documentary, This Is Spinal Tap , directed in 1984 and perhaps still one of his finest films. The basic concept of the mock documentary had been undertaken by many before, most notably by Peter Watkins in the 1960s or more popularly by Woody Allen in Zelig the year before. Reiner's sincerity is apparent in that all satire inherently admits its basis in imitation: and This Is Spinal Tap satirizes the documentary genre, as well as rock documentary and rock bands themselves. A young, hip movie with surprising subtlety, This Is Spinal Tap became a cult film and one of the few Reiner films more popular today than when it was released. Some elements of the rock satire include the early, tragic death of a band member (in this case, a drummer), the physical transformation of the band (a short-lived foray into Kiss-like makeup), the girlfriend involved in the band who virtually destroys it (a la Yoko Ono or Linda McCartney), and of course, life on the road (which includes the most brilliant pseudoverite repartee). Throughout, the film's deadpan rhythms are virtually perfect—for instance, Spinal Tap's manager, Ian, intones, "There's no sex and drugs for Ian, David. I find lost luggage!"

This Is Spinal Tap was followed by a modest, dramatic film, The Sure Thing , a sweet and low-budget coming-of-age story which showed Reiner's abilities to get very good, charming performances—in this case, from his leads Daphne Zuniga and John Cusack. The Sure Thing , if slight, was well observed, a kind of contemporary It Happened One Night offering a fairly credible view of college students, a not inconsiderable task, rarely accomplished. However, Reiner's breakthrough film was the higher-budget Stand by Me. A fully realized film based on a very short, uncharacteristic story by Stephen King, Stand by Me presented a day or so in the lives of four pre-adolescent boys. A derivative coming-of-age story which seemed to emulate Francois Truffaut ( Les Mistons ) or outright imitate Robert Mulligan ( Summer of '42 ), Stand by Me is very entertaining, if manipulative, and designed to appeal to the nostalgia of the yuppie—filled to the brim with references to Pez candy, Walt Disney's Goofy, the Wagon Train television series, and so forth. By the revelations at the end, which propel the characters to their adult fates through the use of voice-over narration, the director clearly has the audience exactly where he wants them for the film's final, sentimental line: "I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was twelve. Jesus, does anyone?" If Stand by Me holds up in the future, it will be as much for the unusually skillful performances Reiner has elicited from his very young actors, including wonderful work from the late River Phoenix in one of his first films.

The Princess Bride was a huge success in 1987. In this film, Reiner told a whimsical fantasy story, changing his style yet again—recalling Spielberg or Walt Disney, even. But an even bigger success came in 1989 with When Harry Met Sally , an absolutely hilarious comedy which made Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan breakaway movie stars. When Harry Met Sally attempted to answer, definitively, the philosophical question: Can straight men and women ever be true friends without sex causing problems? (No.) Virtually every commentator praising the film noted how overwhelmingly it imitated early Woody Allen (the funny period)—the style of joke, the use of music, the characterizations, the philosophical musings, everything. Indeed, it is not far-fetched to call When Harry Met Sally the best Woody Allen film that Allen never made. While the film added to Reiner's reputation in Hollywood and endeared him to audiences, it also began to raise some doubts about his sincerity as an artist, with no personal sensibility clearly emerging.

Misery followed in 1990. Again based on Stephen King material, Misery was in yet another style—showing Reiner to be the most clever study in all of Hollywood—this time emulating Hitchcock and his thrillers, if without Hitchcock's moral sophistication. The story of a woman who keeps a famous writer her prisoner, Misery made Kathy Bates an Academy Award-winning star, and her line "I'm your biggest fan" a kind of cultural catch-phrase. A Few Good Men , released the next year, was a military courtroom drama evoking The Caine Mutiny Court Martial , A Soldier's Story , and several contemporary films of the Reagan/Bush era, like Top Gun , which got great mileage out of men in uniforms. One senses that after having presented James Caan as a weak, passive man in Misery , and after having worked with young people and/or comedians in so many other films, Reiner was eager to show that he could make a man's man kind of film: a solid, Hawksian drama. And indeed, multiple Academy Award nominations followed; the somewhat liberal, anti-establishment theme attracted enough attention to divert from the essential potboiler nature of the project. Probably lasting more than the film's reputation will be the impressive scenery-chewing of Jack Nicholson in the key supporting role.

The critical and popular failure of the sentimental and vapid North in 1994 represented a surprise in the Reiner career, which, through seven films, had shown a steady increase in assurance and judgment, as well as in critical and popular success. North was a juvenile effort uneasily combining a Spielberg-like narrative about a boy who travels across the world to pick out better parents with trite references for their own sake to television and popular culture. Thankfully for Reiner, North was followed in late 1995 by a very strong film, The American President —a funny and moving romantic comedy with deft performances by Annette Bening and Michael Douglas. The American President emerges from Reiner's sympathies for President Bill Clinton, the first liberal Democrat in the White House in twelve years, who was elected in 1992 with great Hollywood support and subsequently excoriated by right-wing commentators over character issues for most of his presidency. The American President , which wears its liberalism proudly on its sleeve, also clearly attacks the domination of the Republican Party by the "Christian Coalition" and its mean-spirited intolerance—as represented by Bob Munson, a Kansas senator played by Richard Dreyfuss who is a clear composite of Kansas Senator Bob Dole and others like Phil Gramm, Newt Gingrich, and Pat Buchanan. The film abounds with fetching parallels to people around Clinton (his young advisor George Stephanopoulos, his daughter Chelsea, and so forth), as well as apparent insights into life in the White House. Certainly, most of Reiner's films have been derivative of other directors, and this time it is Frank Capra, although the influence is acknowledged cheerfully and clearly in the dialogue, and Frank Capra III even serves as the film's first assistant director. Somehow, the Capra vision does not rankle here, not only because it is so suited and similar to Reiner's (although Capra's is darker and more complex), but because it is totally clear that the progressive Reiner believes passionately in his material, which gives the popular form that the film takes a great, contemporary resonance. By the film's end, when the corrupt right-wingers see their influence waning as the president finally gives the speech so many have wished Clinton had given, it is hard—if you possess a liberal vision—not to be moved by Reiner's popular entertainment. Interesting, too, is that Reiner off-screen started taking on the role as spokesperson for liberal Hollywood; indeed, in response to Senator Dole's 1995 (very selective) attacks on Hollywood for trashing American cultural values, Reiner became one of Hollywood's most eloquent and public defenders. Independently, Reiner even proposed and then tirelessly worked for California's Proposition 10, an initiative to impose additional cigarette taxes in order to support children's health issues.

Unfortunately, Reiner's last two theatrical films, Ghosts of Mississippi in 1996 and The Story of Us in 1999 were not particularly well received. The melodramatic Ghosts of Mississippi , which is animated by the director's heartfelt liberal convictions, presents the story of the white prosecutor who won a murder conviction in 1990 against Byron De La Beckwith, the bigot who assassinated civil rights hero Medgar Evers in 1963. Although Ghosts of Mississippi was criticized for its narrative strategy of emphasizing the efforts of its white hero and almost completely ignoring the accomplishments of its black martyr, this criticism seems misguided, for the film's focus is clearly on the failure of white America to take an uncompromising stand for justice. Indeed, Reiner is particularly skillfully at presenting the continuing and subtle racism among his upper-class whites in the Mississippi of 1990. Although arguably a shallow film, Ghosts of Mississippi is nevertheless a melodrama with a bombastic power: when, for instance, the bigoted murderer piously announces "I got tears in my eyes . . . for Dixie," Reiner cuts to the tearful widow of Evers on her knees, scrubbing her husband's blood off their driveway. More ironies accrue as the prosecutor must actually discard his wife—who is named Dixie—in order to effect justice. As is typical in a Reiner film, performances are extraordinary, particularly James Wood's scenery-chewing in old-man make-up as De La Beckwith, which received an Academy award nomination. The Story of Us is harder to defend. A comedy in the vein of When Harry Met Sally , if more melancholy, The Story of Us analyzes the fundamental differences between men and women within the context of a dissolving marriage. Although the film evokes the superior Stanley Donen film Two for the Road , it unfortunately feels tedious and formless, dominated by direct-address, voice-over, and unrelated scenes linked only by its stars looking wistful as they try to figure out what went wrong. That The American President (written by Aaron Sorkin), for instance, is so much more engaging and successful, is a sign of how much Reiner's films really owe to their screenwriters. The Capra-esque happy ending which works so well in The American President , in The Story of Us seems unjustified and unearned—an hypocrisy that contradicts the entire film preceding it, existing only to allow Michelle Pfeiffer her own climactic, histrionic performance opportunity. Unfortunate, too, is that the generally feminist Reiner seems to have lost his bearings, giving in to a casual sexism which implies the woman is more responsible for the marital woes than the man. Clearly, although Reiner can soar when given superior material, he is unable to transcend mediocre material.

Finally, it is necessary to comment on Reiner's overall persona as a performer—for he is a genuinely talented comic actor, clever and canny, who has given a variety of skillful, light performances (notably in Nora Ephron's Sleepless in Seattle and Woody Allen's Bullets over Broadway ). With a remarkable lack of self-consciousness, Reiner seems to be forming a recent acting career from deviously satirical self-portraits, as in Mike Nichols' Postcards from the Edge —a film that comically presents the relationship between a parent and adult child in the film industry (based on Debbie Reynolds and Carrie Fisher) and which undoubtedly resonates for Reiner. He has contributed witty, if brief work, too, in Mike Nichols' 1998 Primary Colors , and a reflexive performance playing himself in Albert Brooks' 1999 film The Muse. Ultimately, as a performer as well as director, Reiner is nothing if not likeable, and seems giving, open, and unpretentious.

—Charles Derry

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: