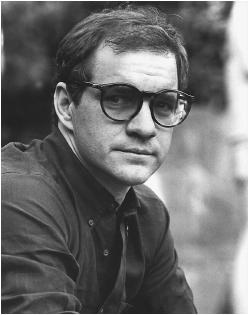

Paul Schrader - Director

Nationality: American. Born: Grand Rapids, Michigan, 22 July 1946; the brother of screenwriter Leonard Schrader. Education: Educated in Ministry of Christian Reformed religion at Calvin College, Grand Rapids, Michigan, graduated 1968; took summer classes in film at Columbia University, New York; University of California at Los Angeles Film School, M.A., 1970. Family: Married actress Mary Beth Hurt, 1983, one daughter, one son. Career: Moved to Los Angeles, 1968; worked as a writer for the Los Angeles Free Press , then became editor of Cinema magazine; first script to be filmed, The Yakuza , 1974; directed his first feature, Blue Collar , 1977. Awards: First Prize Paris Festival, for Blue Collar , 1978; Valladolid International Film Festival Youth Jury Award-Special Mention, for Affliction , 1997; Writers Guild of America Laurel Award for Screen Writing Achievement, 1999. Address: Schrader Productions, 1501 Broadway, Suite 1405, New York, NY 10019, U.S.A. Agent: Jeff Berg, International Creative Management, 8899 Beverly Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90048, U.S.A.

Films as Director and Scriptwriter:

- 1977

-

Blue Collar

- 1978

-

Hardcore

- 1979

-

American Gigolo

- 1981

-

Cat People (d only)

- 1985

-

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters

- 1987

-

Light of Day

- 1988

-

Patty Hearst (d only)

- 1990

-

The Comfort of Strangers (d only)

- 1992

-

Light Sleeper

- 1994

-

Witch Hunt (d only) (for TV)

- 1997

-

Touch ; Affliction

- 1999

-

Forever Mine

Other Films:

- 1974

-

The Yakuza (Pollack) (co-sc)

- 1976

-

Taxi Driver (Scorsese) (sc); Obsession (De Palma) (co-sc)

- 1977

-

Rolling Thunder (Flynn) (sc); Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Spielberg) (co-sc, uncredited)

- 1978

-

Old Boyfriends (Tewkesbury) (co-sc, exec pr)

- 1980

-

Raging Bull (Scorsese) (co-sc)

- 1984

-

De Weg waar Bresson ( The Road to Bresson ) (De Boer, Rood) (doc) (ro as himself)

- 1986

-

The Mosquito Coast (Weir) (sc)

- 1988

-

The Last Temptation of Christ (Scorsese) (sc)

- 1995

-

City Hall (Becker) (co-sc); The Hollywood Fashion Machine (Ely—for TV) (doc) (ro as himself)

- 1999

-

Bringing out the Dead (Scorsese) (sc)

- 2002

-

Dino (Scorsese) (co-sc)

Publications

By SCHRADER: books—

Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer , Berkeley, 1972.

Schrader on Schrader , edited by Kevin Jackson, London, 1989.

Cleopatra Club , New York, 1995.

By SCHRADER: articles—

Schrader, Paul, "Robert Bresson, Possibly," in Film Comment (New York), September/October 1977.

Interview with Gary Crowdus and Dan Georgakas, in Cineaste (New York), Winter 1977/78.

"Paul Schrader's Guilty Pleasures," in Film Comment (New York), January/February 1979.

Interview with M.P. Carducci, in Millimeter (New York), February 1979.

Interview with Mitch Tuchmann, in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1980.

"Truth with the Power of Fiction," interview with Tim Pulleine, in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1984.

Interview with Michel Ciment, in Positif (Paris), June 1985.

"The Japanese Way of Death," interview with David Thomson, in Stills (London), June/July 1985.

Interview with Allan Hunter, in Films and Filming (London), November 1985.

Interview with Karen Jaehne, in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Spring 1986.

Interview with Glenn Rechler, in Cineaste (New York), no. 1, 1989.

Interview with E. Anttila, in Filmihullu (Helsinki), no. 2, 1989.

"Dialogue on Film: Paul Schrader," in American Film (Los Angeles), July/August 1989.

Schrader, Paul, "Does the Letter Still Rate? Porn Has the X, Let's Use an A," in New York Times , 5 August 1990.

"Movie High," interview with Scott Macaulay, in Filmmaker (Los Angeles), no. 1, 1992.

"A Spirit Looking for a Body," interview with H. Barlow, in Filmnews (New South Wales, Australia), no. 9, 1992.

"To Hell with Paul Schrader," interview with L. De Coppet, in Interview (New York), March 1992.

"Awakenings," interview with Gavin Smith, in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1992.

Interview with Michel Ciment, in Positif (Paris), April 1993.

Schrader, Paul, "Paul Schrader on Martin Scorsese," in The New Yorker , 21 March 1994.

Schrader, Paul, " Pickpocket de Bresson," in Positif (Paris), June 1994.

"A Man of Excess," interview with G. Smith, in Sight and Sound (London), January 1995.

Schrader, Paul, "Babes in the Woods," in Artforum (New York), May 1995.

Interview with A.J. Navarro, in Dirigido Por (Barcelona), November 1997.

On SCHRADER: articles—

Toubiana, Serge, and L. Bloch-Morhange, "Trajectoire de Paul Schrader," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), November 1978.

Cuel, F., "Dossier: Hollywood 79: Paul Schrader," in Cinématographe (Paris), March 1979.

Wells, J., " American Gigolo and Other Matters," in Film Comment (New York), March/April 1980.

Sinyard, Neil, "Guilty Pleasures: The Films of Paul Schrader," in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), December 1982.

Eisen, K., "The Young Misogynists of American Cinema," in Cineaste (New York), vol 13, no. 1, 1983.

Gehr, Richard, "Citizen Paul," in American Film (Los Angeles), vol. 13, no. 10, 1988.

Fraser, Peter, " American Gigolo and Transcendental Style," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), vol. 16, no. 2, 1988.

Combs, Richard, "Patty Hearst and Paul Schrader: A Life and a Career in 14 Stations," in Sight and Sound (London), Summer 1989.

Kennedy, Harlan, "The Discomforts of Paul Schrader," in Film Comment (New York), July/August 1990.

Freedman, S.G., "A Fallen Calvinist Pursues His Vision of True Heroism," in The New York Times , 25 August 1991.

Prestor, U., "Paul Schrader," in Ekran (Ljubljana, Yugoslavia, no. 8/9, 1992.

McDonagh, M., "New Schrader Anti-Hero Awakens in Light Sleeper ," in Film Journal (New York), August 1992.

Lopate, Philip, "With Pen in Hand, They Direct Movies," in New York Times , 16 August 1992.

Grimes, W., "The Auteur Theory of Film: Holy or Just Full of Holes?," in New York Times , 20 February 1993.

Mortimer, L., "Desperately Seeking Union: Paul Schrader and Light Sleeper ," in Metro Magazine (St. Kilda West, Victoria, Australia), Winter 1993.

Skal, D.J., " Touch ," in Cinefantastique (Forest Park, Illinois), no. 8, 1997.

Webster, A., "Filmography," in Premiere (New York), February 1997.

* * *

While it is doubtless fanciful and recherché to read Paul Schrader's movies as unmediated reflections of his own life and feelings, it is nonetheless true that the director/screenwriter's "religious fascination with the redeeming hero" echoes his extreme fascination with himself. The incredible urge that his characters have to confess (Schrader frequently resorts to voice-overs and interior monologues), exemplified by Travis Bickle's mutterings in Taxi Driver , Christ's musings on the cross during his Last Temptation , and Patty Hearst's thoughts about her abduction, suggest that his films are firmly rooted in self-analysis. The 1989 book Schrader on Schrader , and the filmmaker's enthusiasm for the bio-pic ( Mishima, Patty Hearst ), a genre that had been more or less moribund since the time of Paul Muni, testify that he does indeed share the Calvinist urge to account for everything, to make his art out of the introspective inventory of his, or somebody else's, life.

Appropriately, for a confirmed fan of the films of Bresson, the image of the condemned man/woman attempting to escape his/her fate is a leitmotif in Schrader's work. He seems obsessed with prison metaphors, with images of captivity. In Patty Hearst , Natasha Richardson is locked up in a cupboard. In Cat People , Nastassia Kinski ends up behind bars, in a zoo—a human captive in a panther's body. Richard Gere, in American Gigolo , is "framed" (he is "framed" for a murder he did not commit and "framed" as the object of the gaze—the camera seems to love him), and the last time we see him, he is reaching out for Lauren Hutton but is separated from her by the glass panel in the prison interview booth. Christ, predictably, ends up on the cross: he too is trapped. A last, sad image of Raging Bull is of Jake La Motta (Robert De Niro) banging his head against his cell wall. Schrader's work abounds in figures cabined, cribbed, and confined. Travis Bickle, that emissary from 1970s America, is a prisoner in the city, a prisoner in his own body, a prisoner behind the wheel of his taxi, a slave to pornography and junk food, and he is trying, in his mildly psychotic way, to free Jodie Foster's child prostitute, who is similarly trapped. Season Hubley in Hardcore is whisked away from a Calvinist Convention, kidnapped by a snuff movie producer, and needs an Ahab/John Wayne figure (George C. Scott) from the suburbs to rescue her, to try to reincarcerate her within the family. Even Schrader's Venice in The Comfort of Strangers , studio-built and full of interminable dark corridors, seems more like San Quentin than a beautiful European city on water.

An American of Dutch/German extraction, Schrader had a strict religious upbringing in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He did not watch as much TV as one might expect, and when it came to the cinema, he was cruelly deprived: incredibly, he saw his first film, The Absent-minded Professor , when he was seventeen. Then came the revelation of Wild in the Country , a lurid Elvis Presley vehicle which gave him his vision on the Road to Damascus: he was captured by the celluloid muse. His Calvinist background, combined with his early career as film historian/critic, makes him among the more academically inclined of mainstream Hollywood filmmakers. He was a Pauline Kael protegé, a "Paulette" as he describes it, and it was Kael's influence which got him into the film course at UCLA. Few of his contemporaries have been fellows of the American Film Institute or have written ineffably unfathomable monographs on transcendental style in the movies of Ozu, Bresson, and Dreyer. He straddles two mutually exclusive cultures, traditions, discourses. On the one hand, he is the film scholar and expert in European and Japanese cinema. On the other, he is the hack Hollywood director and screenwriter. It is a tension that he seems to enjoy. Is he the artist locked up in a commercial catacomb or is he the popular filmmaker, hampered by his own notions of art? Is he, perhaps, just plain religious freak and show-off? "The reason I put that Bressonian ending onto American Gigolo ," he noted, "was a kind of outrageous perversity, saying I can make this fashion-conscious, hip Hollywood movie and at the end claim it's really pure; and in Cat People I can make this horror movie and say it was about Dante and Beatrice."

Sometimes Schrader seems too clever by half. Kael, attacking Patty Hearst , suggested he lacked a basic instinct for moviemaking: "He doesn't reach an audience's emotions." This is probably unfair. His own scripts have a relentless narrative drive, generally toward some kind of judgement day (witness his work with Scorsese). When he is directing another writer's scenario, he can lose that obsessive will to destruction, salvation, damnation. Both Patty Hearst and The Comfort of Strangers —though it must be taxing for any director to try to animate a Pinter script—lack the momentum, the frenetic desire to tell a story, which may be found in the films he wrote himself.

Apparently, he worked with Spielberg on early drafts of Close Encounters , but Spielberg elbowed him off the project because Schrader did not share his Capra-like love of the common man and wanted to make the protagonist a crusading religious fruitcake à la Travis Bickle. Whatever one's reservations about Schrader's evangelism or his tedious self-obsession, he is undoubtedly one of Hollywood's most formally arresting filmmakers. He pays enormous attention to set design. (He has worked frequently with Scarfiotti, Bertolucci's designer on The Conformist. ) He seems equally at home with the lush, magical opulence of New Orleans in Cat People , the sober, almost drama-doc look of Patty Hearst , the glossy, superficial Los Angeles, all hotels, restaurants, and expensive apartments, of American Gigolo , or the stagy, elaborate sets on Mishima. Edgy, prowling tracks (the opening shot of The Comfort of Strangers is a virtuoso effort in camera peripeteia to rival the first few minutes of Welles' Touch of Evil ), a predilection for high angle shots (humans as bugs), and his discerning use of music (he has worked with Philip Glass and Giorgio Moroder, among others) show him as a filmmaker with a consummate love of his craft.

Yet Schrader thrives on controversy. He was sacked from his job as film critic for the Los Angeles Free Press because he gave a debunking review to Easy Rider. American Gigolo was attacked as being homophobic. Mishima provoked an outcry in Japan. The Last Temptation of Christ brought the moral majority out to the picket line. Apparently a student radical in the 1960s, Schrader caricatures the Symbionese Liberation Army, Patty Hearst's abductors, as idiotic mouthers of revolutionary platitudes. His films seem to abound in right-wing visionaries (Travis Bickle, George C. Scott in Hardcore , Mishima, Christopher Walken in The Comfort of Strangers ) and, while he does not straightforwardly endorse their viewpoints, he respects their right to be individuals and their struggle for redemption, a struggle which invariably leaves onlookers dead and dying in the crusading hero's wake. Social historians of American culture and politics in the 1970s and 1980s will find rich pickings in the Schrader oeuvre. Schrader continued his cinematic explorations of characters attempting to purge themselves of their excesses and sins in Light Sleeper , a knowing, sobering film set amid the strata of the New York City drug culture. Symbolically, its scenario is set during a sanitation strike, allowing the streets to be strewn with garbage. Willem Dafoe plays John LeTour, a forty-year-old ex-junkie and "mid-level drug dealer" whose clientele consists of upscale New Yorkers willing to pay big bucks for top-quality product. Both LeTour and Ann (Susan Sarandon), his boss, are fascinating characters. Within the confines of her world, Ann is a celebrity, a legend: the Mayflower Madam of the drug trade. She dresses like a high-powered business executive, dines in fancy restaurants, and tools around town in a chauffeured limousine. She also is shifting from drug dealing to marketing cosmetics. LeTour, too, yearns to go straight: he is having trouble sleeping, and he fears he has run out of luck. However, his redemption will not come easily, a fact that quickly becomes apparent when he runs into Marianne (Dana Delany), his ex-girlfriend and also a former junkie.

On occasion in Light Sleeper , Schrader waxes nostalgic about the "good old days" of drug use, "before crack came," when cocaine was the drug of choice. Otherwise, he graphically depicts the ravages of drugs. His junkies are unromanticized and ultimately pathetic. Despite its top-of-the-line cast, Light Sleeper was too unsexy a film to earn the widespread hype enjoyed by many of Schrader's earlier films.

Touch , the story of a Christ-like character named Juvenal (Skeet Ulrich) who is exploited by various revivalists, fundamentalists, and hucksters, is another of Schrader's films that may be directly linked to his upbringing. It also is one of his lesser films, as it wallows in understatement. He then reemerged in full force with Affliction , based on a novel by Russell Banks, the saga of Wade Whitehouse (Nick Nolte, in a performance that is a model of anguished intensity), a small-town New Hampshire sheriff who is drowning in his demons. His ex-wife despises him; his daughter feels only discomfort as he ineptly attempts to relate to her; and his problems are linked to his abusive father (a riveting, Oscar-winning James Coburn), a dying man who wallows in alcoholic rage—and whom Wade still deeply fears.

Then Schrader revisited the landscape of Taxi Driver by scripting Scorsese's Bringing out the Dead , only here the loner-hero, Frank Pierce (Nicolas Cage), is a burned-out Manhattan paramedic whose soul has been deadened by all the pain he has witnessed, and who finds himself haunted by hallucinations. Taxi Driver and Bringing out the Dead offer alternative visions of the Manhattan of Woody Allen: an upper-middle-class playground where crime and creeps mostly are nonexistent, drug-taking is a chic, recreational sport (rather than a destroyer of souls), and an individual's dysfunction is linked to his psyche (and Brooklyn Jewish upbringing) rather than the muck of his present-day environment.

Frank Pierce and Wade Whitehouse are two more Schrader characters who are prisoners. Pierce's shackles are the slick, dangerous streets of New York between dusk and dawn, while Whitehouse's lockup is his hometown. Unlike his brother, he has not had the good sense to move far, far away, and reinvent himself.

—G.C. Macnab, updated by Rob Edelman

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: