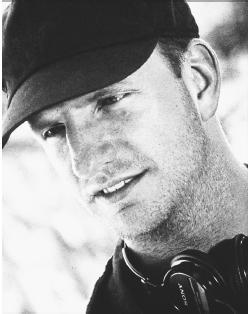

Steven Soderbergh - Director

Nationality:

American.

Born:

14 January 1963, in Atlanta, Georgia.

Education:

High school graduate, 1980.

Family:

Married Betsy Brantley, 1989 (divorced, 1994); one daughter.

Career:

Did odd jobs while writing scripts and directing short films,

1980–85; directed

90125

, a Yes concert film, for MTV, 1986; first feature,

sex, lies, and videotape

, a surprise international success, 1989.

Awards:

Grammy Award for Best Director, for

90125,

1986; Palme d'Or for Best Feature Film, Cannes International Film

Festival, 1989, and Sundance Film Festival Audience Award and Independent

Spirit Awards for Best Feature and Best Director, 1990, for

sex, lies, and videotape

; National Society of Film Critics Best Director Award for

Out of Sight

, 1998

.

Agent:

Patrick Dollard, Dollard Management and Productions, 21361 Pacific Coast

Highway Νm3, Malibu, CA 90265, U.S.A.

Films as Director:

- 1986

-

90215 (doc; for TV)

- 1989

-

sex, lies, and videotape (+ sc, ed)

- 1991

-

Kafka (+ ed)

- 1993

-

King of the Hill (+ sc); "The Quiet Room" (episode of TV series Fallen Angels )

- 1995

-

The Underneath (+ co-sc, uncredited)

- 1996

-

Gray's Anatomy ; Schizopolis (+ sc, ph, ro as Fletcher Munson/Dr. Jeffrey Korchek)

- 1998

-

Out of Sight

- 1999

-

The Limey

- 2000

-

Erin Brockovich ; Traffic

- 2001

-

Ocean's Eleven

Other Films:

- 1993

-

Suture (McGehee) (exec pr)

- 1996

-

The Daytrippers (Mottola) (co-pr)

- 1998

-

Nightwatch (Bornedal) (co-sc); Pleasantville ( Ross) (co-pr)

Publications

By SODERBERGH: book—

sex, lies, and videotape (journal and screenplay), New York, 1990.

On SODERBERGH: book—

Singer, Michael, A Cut Above: 50 Film Directors Talk about Their Craft , Los Angeles, 1998.

On SODERBERGH: articles—

Minsky, Terri, "Hot Phenom," in Rolling Stone (New York), May 18, 1989.

Jacobson, Harlan, "Truth or Consequences," in Film Comment (New York), July-August 1989.

Gabriel, Trip, "Steven Soderbergh: The Sequel," in New York Times Magazine , 3 November 1991.

Werckmeister, O. K., "Kafka 007," in Critical Inquiry , Winter 1995.

Kehr, Dave, "The Hours and Times: The (Film) World according to Steven Soderbergh," in Film Comment (New York), September-October 1999.

Johnston, Sheila, "The Flashback Kid," in Sight and Sound (London), November 1999.

* * *

Steven Soderbergh's work is difficult to characterize as a whole,

considering its remarkable variety. His first four features differ

considerably in both style and subject: a contemporary sexual

drama/comedy, a fantasy thriller set in Kafka's Prague, a portrait

of a child growing up in Depression-era America, and a remake of a classic

film noir. And the next five include a farce too avant-garde even for the

art-house circuit and an altogether conventional Hollywood star vehicle.

Following the sensational success of his first feature,

sex, lies, and videotape

, Soderbergh was often compared to other young independent American

filmmakers, notably Jim Jarmusch and Hal Hartley. However, his film style

has turned out to be much less immediately identifiable (or from a

Hollywood viewpoint, less eccentric) than Hartley's in particular.

Overall, one can say that in his best films, he tells stories in concise

and polished ways, reminiscent of classic Hollywood models, yet with

fresh, unusual structures and surprising turns from scene to scene; and

his cinematography is usually superb, notably in framing and lighting,

though always adaptive to the overall subject and mood.

sex, lies, and videotape

is more than a highly accomplished debut film—it would be highly

accomplished at any stage of a career. In portraying a budding

relationship between a man who is impotent, except when watching his own

video interviews with women on sexual topics, and a woman recoiling from

the discovery that her husband and sister are having an affair, the

writer/director manages to create neither low farce nor soap-operatic

psychodrama. Actually, the film is rather touchingly romantic, in a witty,

gentle, unsoppy sort of way. Soderbergh deftly introduces the four main

characters through a montage of scenes linked by a voiceover of Ann

speaking to her therapist; he moves the story forward with some striking

close-ups and high angle shots, while unobtrusively linking each character

to a special decor (mostly empty spaces in Graham's case). And he

brilliantly structures the climactic scene of Ann taking hold of

Graham's video camera: its second half unfolds only later, when her

unfaithful but furious husband seizes her tape and begins to watch it, at

which point Soderbergh cuts from the video footage to a flashback of Ann

and Graham making the tape. As for the director's handling of the

actors, one might simply note that the film immeasurably boosted the

careers of James Spader and Andie MacDowell and gave Laura San Giacomo a

strong debut. If Peter Gallagher's performance is merely

solid—perhaps because his character is conceived more as a simple

type than the other three—Soderbergh did later provide the actor

with one of his best, most subtle screen roles, in

The Underneath.

Striking into new territory for his eagerly anticipated second feature,

Soderbergh created a work uneasily occupying a space between a European

art film and a plot-driven Hollywood suspense film.

Kafka

has a script that derives from two different kinds of paranoid

world—the literary one of Franz Kafka and the cinematic one of the

political-conspiracy thriller. Its visual style seems inspired by Carol

Reed's

The Third Man

(rather than Orson Welles's version of Kafka's

The Trial)

, and perhaps too blatantly by Terry Gilliam's

Brazil

in the color sequence inside the Castle. The film does have astonishingly

handsome black-and-white cinematography, some quite terrifying moments

involving a shrieking killer, and some droll slapstick humor in the antics

of a pair of office assistants. But there is an awkwardness in having a

protagonist who on one level is the "real" Franz

Kafka—shown as a drudge in an insurance office who writes agonized

letters to his father and fantastic stories like

"Metamorphosis"—but on another level is a reluctant

movie hero drawn into uncovering a sinister organization that turns out to

be diabolical in a much more conventional way than anything in an actual

Kafka story.

King of the Hill has its terrifying moments too, notably in the figure of a snarly bellboy trying to evict the young hero from the hotel room where his father has more or less abandoned him. Indeed, all three of Soderbergh's features following sex, lies, and videotape have a single isolated male protagonist trapped in a world out of his control or comprehension. But King of the Hill also particularly recalls sex, lies, and videotape in its concern with lies and the doubtful knowability of other people. The plot, based upon A. E. Hotchner's memoir, centers upon the efforts of an impoverished twelve-year-old (Jesse Bradford) to pass himself off at school as well-to-do, and upon his need to trust that his suspiciously undemonstrative father (Jeroen Krabbe) will return to him. Overall, the story line is rather dark: the boy not only is exposed as a liar, but loses contact with everyone he loves—in turn, his kid brother, sickly mother, travelling-salesman father, the girl next door, and his roguish best friend—until he is nearly literally reduced to starvation. Yet, in Dickensian fashion, there are also warm, even comical moments and whole episodes, as well as a number of reunions. Soderbergh manages to balance the bleak and joyful elements skillfully, for the most part, though one might wish the cinematography did not have that hazy golden glow that for a time was too commonly used for period pieces.

In choosing to remake the classic film noir Criss Cross , Soderbergh had a perfect vehicle for continuing his fascination with motifs of lies, trust, and seemingly cosmic entrapment within the conventions of a genre that specializes in such concerns. Most impressively, The Underneath has the true noir feel, without aping the black-and-white visuals of the Robert Siodmak original or other 1940s films, or leaning toward parody à la Body Heat , or making a slick melodrama with an unambiguously decent protagonist and an upbeat ending (as in Barbet Schroeder's remake of Kiss of Death , which opened at the same time as The Underneath ). Selecting widescreen Panavision with some very unsettling compositions, and constructing a far more complex flashback structure than the original film had, Soderbergh flawlessly plays out the drama of an ex-gambling addict still obsessed with his ex-wife (now married to a gangster) and drawn into an armored car robbery that betrays his kindly mentor. There is a telling moment when Michael's new girlfriend, sensing his mind on other things, remarks, "You're not very present tense": a perfect description of a noir hero trapped in webs of the past and fearing the future. In the film's fluid flashback structure we indeed see Michael's life fluctuating between three timelines, and only gradually put the puzzle together: his selfish or addictive past (marked by his having a beard); his ethical/familial/sexual entanglements when he returns to his hometown; and (in what may be considered flashforwards) the day of the robbery, marked by bluish lighting and time subtitles, like "6:02 p.m." Only at the violent moment of the robbery, more than an hour into the film, are we fully "caught up" in time; and at this point Soderbergh proceeds to a daring seven minutes of POV shots as a delirious Michael watches various characters address him in his hospital bed. This is followed by a set piece of suspense, involving a possible assassin, that owes something to Siodmak's film but is so superbly gauged that it is a classic in itself.

Receiving mixed reviews and low attendance at its opening, The Underneath quickly disappeared from theatres—an undeserved fate for one of the best of the neo-noirs, and perhaps Soderbergh's most accomplished work after sex, lies, and videotape. Taking a break from conventional storytelling, he shot a Spaulding Gray performance piece, Gray's Anatomy , and then the curious Schizopolis , which he wrote, photographed, and starred in, playing both a minor executive for a Scientology-like firm and a dentist who is having an affair with the executive's wife. Soderbergh proves to be a deft enough comic actor, and writes some ingenious dialogue for husband and wife in the form of summaries. (Upon the wife's return home "from a movie": "Obligatory question about the evening's activities." "Oh, qualified, vaguely positive reply.") Less amusing are scenes when his character is dubbed into Italian or French, or when men in white outfits are chasing a madman wearing only a t-shirt with the movie's name on it. Parts of the film toy with narrative levels in a Monty Python manner, but the comic timing often seems vaguely off.

Soderbergh moves back into fine form, however, and critical and popular success, with the Elmore Leonard adaptation Out of Sight . Too playful to be properly called a thriller, though it features jailbreaks, crazed killers, graphic violence, and a climactic armed robbery caper, the film provides perfect roles for George Clooney as a cool and clever petty criminal and Jennifer Lopez as a U.S. Marshall trying to bring him in but (sort of) falling in love with him. The film's racial and gender politics may be open to question (black men are either villains or loyal sidekicks, and Lopez is drawn to Clooney even though he kidnaps her upon their first meeting), but the performances are accomplished, the jazzy soundtrack sets a laid-back mood, and the editing is beautifully fluid even with the film's extremely intricate flashback/flashforward structure. All of these virtues come together in a scene of seduction with snow falling outside a hotel window, a model of elegant cinematic romance.

The Limey uses flashbacks and flashforwards too, but in less fluid, more flashily self-conscious way. Here the technique and some of the plot recall John Boorman's 1967 Point Blank . Terrence Stamp is suitably hard-boiled as an ex-con taking revenge on a whole slew of younger mobsters, but Peter Fonda as the head villain seems a gimmick in casting, and the tale, despite the narrative games, is rather one-dimensional, with a weak resolution.

Perhaps the most surprising turn in Soderbergh's career to date is not his choice of the muckraking drama Erin Brockovich for his next project, but his actual direction of it. From the opening close-up of Julia Roberts the film is clearly gauged as a vehicle for the star, whose demeanor is just a little too classy, and her outfits a little too calculatedly vulgar, for her to be fully plausible as the real-life redneck lawyer's assistant who brought a successful lawsuit against a powerful utility for poisoning people's groundwater. But the casting is not the problem: it is that virtually every shot, every character's reaction to every story development, seems utterly predictable from beginning to end. One can only hope that the film's huge box-office success will not keep Soderbergh from making the deftly structured, surprising dramas he has achieved in the past.

—Joseph Milicia

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: