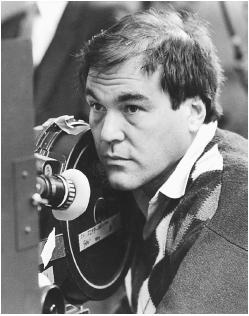

Oliver Stone - Director

Nationality: American. Born: New York City, 1946. Education: Studied at Yale University, dropped out, 1965; studied filmmaking under Martin Scorsese, New York University, B.F.A., 1971. Military

Films as Director and Scriptwriter:

- 1974

-

Seizure

- 1979

-

Mad Man of Martinique

- 1981

-

The Hand

- 1986

-

Salvador (+ pr, co-sc); Platoon

- 1987

-

Wall Street (co-sc)

- 1988

-

Talk Radio (co-sc)

- 1989

-

Born on the Fourth of July (co-sc)

- 1991

-

The Doors (co-sc, + uncredited role as film professor); JFK (+ pr)

- 1993

-

Heaven and Earth (+ pr)

- 1994

-

Natural Born Killers

- 1995

-

Nixon (+ pr)

- 1997

-

U Turn

- 1999

-

Any Given Sunday (+ exec pr)

Other Films:

- 1973

-

Sugar Cookies (Gershuny) (co-pr)

- 1978

-

Midnight Express (Parker) (sc)

- 1982

-

Conan the Barbarian (Milius) (co-sc)

- 1983

-

Scarface (De Palma) (sc)

- 1985

-

Year of the Dragon (Cimino) (sc)

- 1986

-

8 Million Ways to Die (Ashby) (co-sc)

- 1991

-

The Iron Maze (exec pr)

- 1992

-

South Central (exec pr); Zebrahead (exec pr)

- 1993

-

Dave (role as himself); The Last Party (role as himself); The Joy Luck Club (exec pr); Wild Palms (for TV) (exec pr)

- 1994

-

The New Age (exec pr)

- 1995

-

Indictment: The McMartin Trial (for TV) (exec pr)

- 1996

-

Freeway (exec pr); Killer: Journal of a Murder (exec pr); The People vs. Larry Flint (pr)

- 1998

-

The Last Days of Kennedy and King (exec pr); Savior (pr)

- 1999

-

Chains (exec pr); The Corrupter (exec pr)

Publications

By STONE: books—

Platoon and Salvador: The Screenplays , with Richard Boyle, Cranbury, New Jersey, 1987.

Oliver Stone's Heaven and Earth , with Michael Singer, Boston, 1993.

JFK: The Book of the Film , with Zachary Sklar, New York, 1992.

A Child's Night Dream , St. Martin's Press, 1997.

By STONE: articles—

Interview with Nigel Floyd, in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), January 1987.

Interview with Pat McGilligan, in Film Comment (New York), January/February 1987.

Interview with M. Burke, in Stills (London), 29 February 1987.

Interview with Louise Tanner, in Films in Review (New York), March 1987.

Interview with M. Sineux and Michel Ciment, in Positif (Paris), April 1987.

Interview with Alexander Cockburn, in American Film (Washington D.C.), December 1987.

Interview with Gary Crowdus, in Cineaste (New York), vol. 16, no. 3, 1988.

Interview with M. Tessier and others, in Revue du Cinéma (Paris), April 1989.

Interview with Mark Rowland, in American Film (Washington, D.C.), March 1991.

Interview with David Breskin, in Rolling Stone (New York), 4 April 1991.

Interview in Time (New York), 23 December 1991.

Interview with David Ansen, in Newsweek (New York), 23 December 1991.

Interview with Jeff Yarbrough, in Advocate (New York), 7 April 1992.

Interview with Gavin Smith, in Film Comment (New York), January/February 1994.

Interview with Gregg Kilday, in Entertainment Weekly (New York), 14 January 1994.

Interview with Graham Fuller, in Interview (New York), September 1994.

Interview with Nathan Gardels, in New Perspectives (Toronto), Spring 1995.

"The Dark Side: Nixon ," an interview with Gavin Smith and José Arroyo, in Sight and Sound (London), March 1996.

Interview with Ric Gentry, in Post Script (Commerce), Summer 1996.

"Ten Years, Ten Films," an interview with Erik Bauer, in Creative Screenwriting (Washington, D.C.), Fall 1996.

"Past Imperfect: History according to the Movies: History, Dramatic Licence, and Larger Historical Truths," an interview with Mark C. Carnes and Gary Crowdus, in Cineaste (New York), March 1997.

"Desert Noir: How the Southwest was Redone," an interview with Andrew O. Thompson, in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), October 1997.

"The Sweet Hell of Success," an interview with P. Biskind, in Premiere (Boulder), October 1997.

On STONE: books—

Beaver, Frank, Oliver Stone: Wakeup Cinema , New York, 1994.

Riordan, James, Stone: The Controversies, Excesses, and Exploits of a Radical Filmmaker , New York, 1994.

Salewicz, Chris, Oliver Stone , New York, 1998.

Toplin, Robert Brent (editor), Oliver Stone's USA: Film, History, and Controversy , Lawrence, 2000.

On STONE: articles—

Chase, Chris, "Good Fortune Has Creator of Hand Nervous," in New York Times , 15 May 1981.

Sklar, Robert, and others, " Platoon on Inspection: A Critical Symposium," in Cineaste (New York), vol. 15, no. 4, 1987.

Peary, Gerald, "The Ballad of a Haunted Soldier," in Maclean's (Toronto), 30 March 1987.

Boozer, Jack, Jr., " Wall Street : The Commodification of Perception," in Journal of Popular Film and Television (Washington, D.C.), vol. 17, no. 3, 1989.

Corliss, Richard, "Who Cares?," in Film Criticism (Meadville, Pennsylvania), vol. 25, no. 1, 1989.

Jones, G., "Trash Talk: Oliver Stone's Talk Radio ," in Enclitic (Los Angeles), vol. 11, no. 2, 1989.

Wrathall, J., "Greeks, Trojans and Cubans—Oliver Stone," in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), October 1989.

Denby, David, "Days of Rage," in New York , 18 December 1989.

Klawans, Stuart, " Born on the Fourth of July ," in Nation (New York), 1 January 1990.

Kauffman, Stanley, "The Battle after the War," in New Republic (New York), 29 January 1990.

Simon, John, "Wild Life," in National Review (New York), 5 February 1990.

Hoberman, J., "Out of Order," in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1991.

Horton, Robert, "Riders on the Storm," in Film Comment (New York), May/June 1991.

Schiff, Stephen, "The Last Wild Man," in New Yorker , 8 August 1994.

Cieutat, Michel, and others, in Positif (Paris), April 1996.

Rosenbaum, R., "The Pissing Contest," in Esquire , December 1997.

Tobin, Yann, and Michael Henry, in Positif (Paris), January 1998.

Pizzello, Chris, "Smash-Mouth Football," in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), January 2000.

On STONE: film—

Oliver Stone: Inside Out (for TV), 1992.

* * *

Anyone attempting with any degree of success, both artistic and commercial, to make overtly political movies that sustain a left-wing position within the Hollywood cinema of the 1980s and 1990s deserves at least our respectful attention. In fact, Oliver Stone's work dramatizes, in a particularly extreme and urgent form, the quandary of the American left-wing intellectual.

Platoon and Wall Street provide a useful starting point, as they share the same basic structure. A young man (Charlie Sheen, in both films) has to choose in terms of values between the Good Father (Willem Dafoe, Martin Sheen) and the Bad Father (Tom Berenger, Michael Douglas); he learns to choose the Good Father and destroy the Bad. The opposition is very similar in both cases: the Good Father is a liberal with a conscience, aware of the impossibility of changing or radically affecting the general situation but committed to the preservation of his personal integrity; the Bad Father has no conscience and no integrity to preserve, and this, combined with a total ruthlessness, is what equips him to survive (until the dénouement) and makes him an insidiously seductive figure. The Bad Father is completely adapted to a system that the Good Father can protest against but do nothing to change. The young man can exact a kind of individual justice by destroying the Bad Father, but the system remains intact.

Platoon and Wall Street do not represent Stone's work at its best: their targets are a bit too obvious, the characteristic rage comes too easily, tinged with self-righteousness, so that the alienating aspects of his manner—the heavy stylistic rhetoric, the emotional bludgeoning—are felt at their most obtrusive. But the two films encapsulate the quandary—one might say the blockage —that is treated more complexly elsewhere: what does one fight for within a system one perceives as totally corrupt but in which the only alternative to capitulation is impotence?

The fashionable buzz-phrase "structuring absence" becomes resonant when applied to Stone's films: in the most literal sense, his work so far is structured precisely on the absence of an available political alternative, which could only be a commitment to what is most deeply and hysterically taboo in American culture, a form of Marxist socialism. There is a curious paradox here which Americans seem reluctant to notice: Lincoln's famous formula, supposedly one of the foundations of American political ideology, "Government of the people, by the people and for the people," could only be realized in a system dubbed, above all else, "un-American" (American capitalism, as Stone sees very clearly, is government by the rich and powerful for the rich and powerful). In both Salvador and Born on the Fourth of July the protagonist declares, at a key point in the development, "I am an American, I love America," and we must assume he is speaking for Stone. But we must ask, which America does he love, since the American actuality presented in both films is unambiguously and uniformly hateful? What is being appealed to here is clearly a myth of America, but the films seem, implicitly and with profound unease, to recognize that the myth cannot possibly be realized, that capitalism must take the forms it has historically taken. Hence the sense one takes from the films of a just but impotent rage: without the availability of the alternative there is no way out.

This is nowhere clearer than in Salvador , one of Stone's strongest, least flawed works and a gesture of great courage within its social-political context. While in American capitalist democracy it is still possible to make a film like Salvador (the equivalent in Stalinist Russia would have been unthinkable), it is not possible for the film to go further than it does, to take the necessary, logical step. Impotent rage is permissible, the promotion of a constructive alternative is not. Stone's films can be acceptable, even popular, even canonized by Academy Awards precisely because their ultimate effect, beyond the rage, is to suggest that things cannot be changed (as indeed they cannot, while one remains within the system). Salvador offers a lucid and cogent analysis of the political situation, a vivid dramatization of historical events (the death of Romero, the rape and murder of the visiting Nicaraguan nuns), and an outspoken denunciation of American intervention. Neither does it chicken out at the end: the final scene, where the protagonist at last gets his lover and her two children over the border into the "land of the free," to have them abruptly and brutally sent back by American security officers, is as chilling as anything that modern Hollywood cinema has to offer. But the film's attitude to the concept of a specifically socialist revolution (as opposed to a vague notion of people "fighting for their freedom") is thoroughly cagy and equivocal. Nothing is done to demystify the habitual American conflation of socialism and Marxism with Stalinism.

All the film can say is that the threat of a general "Communist" takeover is either imaginary or grossly exaggerated (if it were not, presumably the horrors we are shown would all be justified or at least pardonable), that the Salvadoreans, like good Americans, just want their liberty, and that America, in its own interests, has betrayed its founding principles by intervening on the wrong side.

Born on the Fourth of July recapitulates the earlier film's force, rage, and outspokenness, and also its impasse. It seems to be weakened, however, by its final construction of its protagonist as a redeemer-hero. Ron Kovic, by the end of the film, in realizing (with whatever irony) his mother's dream that he would one day speak before thousands of people saying wonderful things, at once regains his full personal integrity and sense of self-worth and offers an apparent political escape by revealing the "truth." But recent history has shown many times that the revelation of truth can be very readily mythified and absorbed into the system (the Oscar awards and nominations for Stone's movies represent an exact equivalent).

Talk Radio received no such accolades and seems generally regarded as a minor, marginal work. On the contrary, it is arguably Stone's most completely successful film to date and absolutely central to his work, to the point of being confessional. It has been taken as more an Eric Bogosian movie than a Stone movie. We can credit Stone with firmer personal integrity and higher ambitions than are evidenced by Barry Champlain (Bogosian's character), but, that allowance made, Stone has found here the perfect "objective correlative" for his own position, his own quandary. Champlain's rage, toppling over into hysteria, parallels the tone of much of Stone's work and identifies one of its sources, the frustration of grasping that no one really listens, no one understands, no one wants to understand; the sense of addressing a people kept in a state of mystification so complete, by a system so powerful and pervasive, that no formal brainwashing could improve on it (this "reading" of the American public is resumed in Born on the Fourth of July ). The film is indeed revelatory, and very impressive in its honesty and nakedness.

In the 1990s, Stone's career entered a new phase as the director became even more commercially successful while raising the ante of political controversy. His earlier films, especially Platoon , had successfully exploited classic realist techniques—especially the device of a likeable main character—to arouse audience sympathy for a radical point of view: that the system deals in death, not life, and counts as enemies all who oppose it, including "good" Americans. Classic realism, however, leads the spectator toward emotional catharses that blunt the point of such political perceptions; furthermore, the narrative closure required in such texts suggests a victory for the protagonists of good will even as the political problems so tellingly enunciated are transcended. Of Stone's recent films, only Heaven and Earth , which completes his Vietnam trilogy, remains more or less within the regime of classic realism. Based on the autobiographical novels of Le Ly Hayslip, Heaven and Earth also offers a main character—a young Vietnamese woman—who is both sympathetic and socially typical, who offers, in short, an ideal emotional and narrative vantage point for the representation—poignant if not objective or detailed—of Vietnamese history since 1953. Le Ly is abused and manipulated by the successive regimes in her village—French, South Vietnamese, Viet Cong—only to be "rescued" by a burned-out GI who takes her to an America concerned only with materialism and its own comfort. This ambitious film never individualizes, hardly humanizes its main character (who heroically resists Americanization by an entrepreneurship that allows her to live alone and return to Vietnam). With its startling visual stylization, artful use of disorienting editing, and expressionistic mise-en-scène, Heaven and Earth treats its subject with an operatic grandeur. The abandonment of realism (with itscarefully restrained stylization) for expressionism is also evident in The Doors , which takes as its subject yet another—for Stone—heroic rebel of the 1960s, musician/poet Jim Morrison. Here visual and aural stylizations are motivated by Stone's desire to pay homage to the psychodelism of the period, even as they "express" the artistic rebellion of Morrison's music. As in Heaven and Earth , the film is less about a character than a zeitgeist , but many reviewers and spectators were disappointed by Stone's lack of emphasis on narrative and complex character.

A further, though never complete rejection of realism is to be found in the three Stone films that have found the most commercial success, even as they have aroused the greatest political controversy (making Stone a frequent guest on TV talk shows to defend his latest work and simultaneously plug it). Natural Born Killers , though ostensibly set in the 1990s, actually constructs its own, nightmarish version of American reality. Following Brecht, Stone here revives an American myth—the outlaw couple à la Bonnie and Clyde—but empties the outrageously violent attack on family and society perpetrated by Mickey and Mallory of all emotional content through two defamiliarizing techniques: a fragmentary, Eisensteinian montage that prevents any scene from achieving a reality effect; and acting that avoids naturalism at all costs. If Platoon uses the violence of war for melodramatic effect, Natural Born Killers eschews emotion of any kind to make a political point: the murderous connection between the deep-seated pathology of American family life and the reprehensible tendency for the media to exploit the desire of the abused and battered to find some kind of identity and self-worth. The result is the most intellectually profound and cerebral contemplation of violence in American life since Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch. Stone, however, has not been satisfied to transcend the historical through mythopoeia and stylistic virtuosity (in the manner of, say, Jim Morrison). His conception of the film director's social role is the most enlarged since the time of D. W. Griffith, whose career his own has in part mirrored. What the Civil War was for Griffith's generation, the Kennedy assassination has been for Stone's: a defining historical event, seen rightly or wrongly as the source of subsequent developments. JFK is Stone's attempt to argue that case: not simply to advance yet another conspiracy theory, but to identify the death of Kennedy as the beginning of a deterioration in American life that has not yet come to an end. Like Griffith, Stone attempted a paradoxical recreation of history: a film that, he argues, is "true" to the facts and yet, making use of dramatic license, creates its own facts as an interpretation, a possible version of history. Like Griffith, Stone has been much attacked for so doing, even as his film has reopened interest in an event and its aftermath for a new generation. JFK uneasily joins two stylistic regimes: a classic realist narrative (the pursuit of the truth by a sympathetically presented main character, district attorney Jim Garrison) and a highly rhetorical, expressionistic recreation of the events under investigation. Of course, Garrison, like Stone's other heroes, fails to do more than the right thing: the vaguely evoked fascistic cabal of southern businessmen and loose cannon Cubans emerges unscathed after pinning the rap on hapless Lee Harvey Oswald. Like Heaven and Earth, JFK ultimately turns nostalgically toward a past as yet unspoiled by the fall into political violence.

Nixon , in contrast, is less oriented toward an event and an era than toward political biography. In the extensively annotated published screenplay, Stone answers his expected critics by pointing to the historical record as a source for the film's material. In that book, Stone insists that his story of Nixon is a classically tragic tale of the essentially good man who overreaches and thereby dooms himself to disgrace. The resulting film, however, is disappointingly simplistic. Nixon becomes a bumbling, foul-mouthed fool whose physical and political gaffes define his relations with others (their constant disapproval is evoked by numerous reaction shots). This interpretation is very much at odds with the substance of the political record and does nothing to explain the shifting tides of popular sentiment that swept Nixon into office and returned him for a second term. Choosing a subject for which he could feel little sympathy, Stone reveals in Nixon the limits of his political vision, which, like Griffith's, depends too much on the melodramatic binarism of heroes and villains.

—Robin Wood

As not in JFK , the opposition of a classic realist regime (the film's investigational structure, a la Citizen Kane , its most obvious model) to an expressionistically represented subjectivity (Nixon's flow of memories) produces little more than confusion for anyone not absolutely familiar with the detailed factual record of Nixon's presidency. Griffith's genius lay in his ability, if that is what it was, to tell a complicated story in simple but evocative images. In this he was followed by the other great cinema historian, Sergei Eisenstein. Stone's ponderous record of the American decline exemplified and contributed to by Nixon fails to tell a story to which anyone not a member of the chorus of the converted would likely attend or even be able to follow.

Stone's work in the closing years of the decade signals a further decline. U-Turn moves away from political filmmaking toward the exploding of a popular genre—the neo-noir erotic thriller—through the same ostentatious stylistic excesses that made some political sense in JFK and Nixon (since they were a calculated Brechtian rhetoric), but here seem so much empty, facetious posing. Sean Penn offers an excellent performance as a petty criminal trapped by bad luck and his own ineptitude in a nightmare landscape (reminiscent of the world Welles limns in Touch of Evil , the paranoid masterpiece that Stone consciously evokes). Yet the film is strangely uninvolving, full of oneiric imagery signifying nothing. Unlike many neo-noir films, U-Turn says nothing new about the discontents of gender or the existential frustrations of the American dream. We are hardly surprised that in the bloodbath finale of cross and double cross the hero thinks he has broken the hold of bad fortune only to realize that the femme fatale, now dead by his hand, has taken the keys to the car that offers his only chance of escape. The same subject matter is treated with more wit and narrative finesse in Red Rock West , The Last Seduction , and other neo-noir programmers.

Stone returned to the big subject in Any Given Sunday , where he attempts to anatomize professional football, which we are implicitly asked to accept as a quintessence of American values, discontents, and dreams. Despite a huge expenditure on what are intended to be graphic depictions of the on-field struggle, Any Given Sunday seems surprisingly ill-informed on the sport and often fails to represent it meaningfully or clearly (for example, the plot involves a young black quarterback who leads the team to temporary success by making up plays in the huddle, an "innovation" we are asked to understand as both plausible and impressive). The struggle in which Stone is more interested takes place in the corporate board room and in the players' luxurious homes. Here Stone proves incapable of capturing quickly and unforgettably the ambience of such a life on the edge and at the top (making Martin Scorsese's evocation of Las Vegas in Casino seem all that more impressive). The narrative, unsurprisingly, comes down to a big game that the teams wins for the aging, jaded coach whose job is in jeopardy (another sad-faced portrayal by Al Pacino of a "godfather" in decline). Overlong, self-indulgent, and unconvincing, Any Given Sunday fails to add anything to our understanding of professional sports, or of the athletes and businessmen who control them.

—updated by R. Barton Palmer

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: