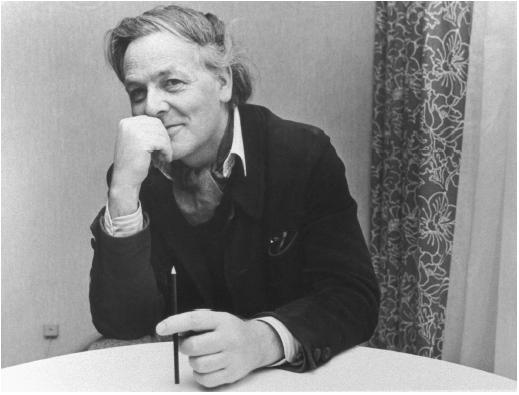

Hans-Jurgen Syberberg - Director

Nationality: German. Born: Nossendorf, Pomerania, 8 December 1935. Education: Educated in literature and art history, Munich. Career: Lived in East Berlin, then moved to West Germany, 1953;

Films as Director:

- 1965

-

Fünfter Akt, siebte Szene. Fritz Kortner probt Kabale und Liebe ( Act Five, Scene Seven. Fritz Kortner Rehearses Kabale und Liebe ); Romy. Anatomie eines Gesichts ( Romy. Anatomy of a Face ) (doc)

- 1966

-

Fritz Kortner spricht Monologe für eine Schallplatte ( Fritz Kortner Recites Monologues for a Record ) (doc); Fritz Kortner spricht Shylock ( Fritz Kortner Recites Shylock ) (short; extract from Fritz Kortner spricht Monologe . . . ); Fritz Kortner spricht Faust ( Fritz Kortner Recites Faust ) (short; extract from Fritz Kortner spricht Monologe . . . ); Wilhelm von Kobell (short, doc)

- 1967

-

Die Grafen Pocci—Einige Kapitel zur Geschichte einer Familie ( The Counts of Pocci—Some Chapters toward the History of a Family ) (doc); Konrad Albert Pocci, der Fussballgraf vom Ammerland—Das vorläufig letzte Kapitel einer Chronik der Familie Pocci ( Konrad Albert Pocci, the Football Count from the Ammerland—Provisionally the Last Chapter of a Chronicle of the Pocci Family ) (extract from the preceding title)

- 1968

-

Scarabea—Wieviel Erde braucht der Mensch? ( Scarabea— How Much Land Does a Man Need? )

- 1969

-

Sex-Business—Made in Passing (doc)

- 1970

-

San Domingo ; Nach Meinem letzten Umzug ( After My Last Move ); Puntila and Faust (shorts; extracts from the preceding title)

- 1972

-

Ludwig II—Requiem für einen jungfräulichen König ( Ludwig II—Requiem for a Virgin King ); Theodor Hierneis oder: Wie man ehem. Hofkoch wird ( Ludwig's Cook )

- 1974

-

Karl May

- 1975

-

Winifred Wagner und die Geschichte des Hauses Wahnfried von 1914–1975 ( The Confessions of Winifred Wagner )

- 1977

-

Hitler. Ein Film aus Deutschland ( Hitler, a Film from Germany ; Our Hitler ) (in four parts: 1. Hitler ein Film aus Deutschland [ Der Graal ]; 2. Ein deutscher Traum ; 3. Das Ende eines Wintermärchens ; 4. Wir Kinder der Hölle )

- 1983

-

Parsifal

- 1985

-

Die Nacht

- 1987

-

Penthesilea

- 1989

-

Die Marquise Von O

- 1993

-

Syberberg filmt Brecht ( Syberberg Films Brecht ) (+ pr, ed, ph)

- 1994

-

Ein Traum, was sonst ( A Dream, What Else? )

Publications

By SYBERBERG: books—

Zum Drama Friedrich Durrenmatts; zwei modellinterpretationen zur Wesensdentung des modernen Dramas , Munich, 1963.

Le Film, musique de l'avenir , Paris, 1975.

Syberberg Filmbuch , Munich, 1976.

Hitler, ein Film aus Deutschland , Reinbek bei Hamburg, 1978.

Die Freudlose Gesellschaft: Notizen aus dem Letzten Jahr , Munich, 1981.

Parsifal, ein Filmessay , Munich, 1982.

Der Wald Steht Schwarz und Schweiger, Neue Notizen aus Deutschland , Zurich, 1984.

By SYBERBERG: articles—

Interview with A. Tournès, in Jeune Cinéma (Paris), December/January 1972/73.

"Forms of Address," interview and article with Tony Rayns, in Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1974/75.

Interview with M. Martin, in Ecran (Paris), July 1978.

"Form ist Moral: 'Holocaust' Indiz der grössten Krise unserer intellektuellen Existenz," in Medium (Frankfurt), April 1979.

Interview with B. Erkkila, in Literature-Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), October 1982.

Interview with I. Schroth, in Filmfaust (Frankfurt), October/November 1985.

"Sustaining Romanticism in a Postmodernist Cinema," an interview with Christopher Sharrett, in Cineaste (New York), vol. 15, no. 3, 1987.

"S'approprier le monde," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), May 1991 (supplement).

Berlin Snell, Marilyn, "Germany's New Nostalgia: How Benign?," in Harper's Magazine (New York), March 1993.

"Fassbinder, a mediahos," in Filmvilag (Budapest), no. 3, 1994.

On SYBERBERG: books—

Franklin, James, New German Cinema: From Oberhausen to Hamburg , Boston, 1983.

Phillips, Klaus, editor, New German Filmmakers: From Oberhausen through the 1970s , New York, 1984.

Rentschler, Eric, editor, West German Filmmakers on Film: Visions and Voices , New York, 1988.

Elsaesser, Thomas, New German Cinema: A History , London, 1989.

Santner, Eric L., Stranded Objects: Mourning, Memory, and Film in Postwar Germany , Ithaca, New York, 1990.

Socci, Stefano, Hans Jurgen Syberberg , Florence, 1990.

On SYBERBERG: articles—

Pym, John, "Syberberg and the Tempter of Democracy," in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1977.

Sauvaget, D., "Syberberg: dramaturgie, anti-naturaliste et germanitude," in Image et Son (Paris), January 1979.

"Syberberg Issue" of Revue Belge du Cinéma (Brussels), Spring 1983.

Article, in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1985.

Rockwell, John, "An Elusive German Director Re-emerges in Edinburgh," in New York Times , 2 September 1992.

Goettler, F., "Ein Leitstrahl fuer Kortner und Brecht," in Filmwaerts (Hannover), December 1993.

* * *

The films of Hans-Jurgen Syberberg are at times annoying, confusing, and overlong—but they are also ambitious and compelling. In no way is he ever conventional or commercial: critics and audiences have alternately labeled his work brilliant and boring, absorbing and pretentious, and his films today are still rarely screened. Stylistically, it is difficult to link him with any other filmmaker or cinema tradition. In this regard he is an original, the most controversial of all the New German filmmakers and a figure who is at the vanguard of the resurgence of experimental filmmaking in his homeland.

Not unlike his contemporary, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Syberberg's most characteristic films examine recent German history: a documentary about Richard Wagner's daughter-in-law, a close friend of Hitler ( The Confessions of Winifred Wagner ); his trilogy covering 100 years of Germany's past ( Ludwig II: Requiem for a Virgin King, Karl May , and, most famously, Hitler, A Film from Germany , also known as Our Hitler ). These last are linked in their depictions of Germans as hypocrites, liars, and egocentrics, and in the final part he presents the rise of the Third Reich as an outgrowth of German romanticism.

Even more significantly, Syberberg is concerned with the cinema's relationship to that history. Our Hitler , seven hours and nine minutes long, in four parts and 22 specific chapters, is at once a fictional movie, a documentary, a three-ring circus (the "greatest show on earth"), and a filmed theatrical marathon. The Führer is presented with some semblance of reality, via Hans Schubert's performance. But he is also caricatured, in the form of various identities and disguises: in one sequence alone, several actors play him as a house painter, Chaplin's Great Dictator, the Frankenstein monster, Parsifal (Syberberg subsequently filmed the Wagner opera), and a joker. Hitler is also portrayed as an object, a ventriloquist's doll, and a stuffed dog. In all, twelve different actors play the role, and 120 dummy Führers appear in the film. The result: Syberberg's Hitler is painted as both a fascist dictator who could have risen to power at any point in time in any number of political climates (though the filmmaker in no way excuses his homeland for allowing Hitler to exist, let alone thrive), and a monstrous movie mogul whose Intolerance would be the Holocaust.

Syberberg unites fictional narrative and documentary footage in a style that is at once cinematic and theatrical, mystical and magical. His films might easily be performed live ( Our Hitler is set on a stage), but the material is so varied that the presence of the camera is necessary to thoroughly translate the action. The fact that his staging has been captured on celluloid allows him total control of what the viewer sees at each performance. Additionally, the filmmaker is perceptibly aware of how the everyday events that make up history are ultimately comprehended by the public via the manner in which they are presented in the media. History is understood more by catchwords and generalities than facts. As a result, in this age of mass media, real events can easily become distorted and trivialized. Syberberg demonstrates this in Our Hitler by presenting the Führer in so many disguises that the viewer is often desensitized to the reality that was this mass murderer.

"Aesthetics are connected with morals," Syberberg says. "Something like Holocaust is immoral because it's a bad film. Bad art can't do good things." He commented that "my three sins are that I believe Hitler came out of us, that he is one of us; that I am not interested in money, except to work with; and that I love Germany." Our Hitler , and his other films, clearly reflect these preferences.

In recent years, Syberberg has remained relatively inactive as a filmmaker. None of his latter work has earned him the visibility, let alone the acclaim, of his earlier films. Since Parsifal , his version of the Wagnerian opera which was his most widely seen film, he has collaborated only with one of that film's stars, Edith Clever. Their artistic ventures have included a number of theatrical monologues, a few of which have been videotaped or filmed. The series commenced with Die Nacht , a six-hour-long examination of how an individual may act or what an individual may ponder deep into the night.

Syberberg, however, has spoken out on issues relating to his homeland. He especially is troubled by the Americanization of world culture, and has hypothesized that the resurgence of neo-Nazism in Germany, especially among the nation's youth, is a natural response to the hollowness of the capitalist culture which enveloped Germany in the post-World War II years. Thus, even in the wake of German unification, the memory of Hitler—despite the fact that he ultimately brought catastrophe and anguish to Germany—continues to influence and mold the national psyche.

—Rob Edelman

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: