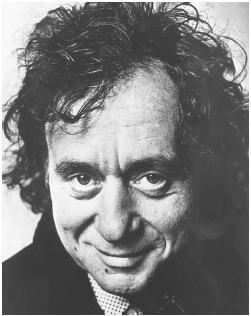

Frederick Wiseman - Director

Nationality:

American.

Born:

Boston, 1 January 1930.

Education:

Williams College, B.A., 1951; Yale Law School, L.L.B., 1954; Harvard

University.

Family:

Married Zipporah Batshaw, 29 May 1955, two sons.

Military Service:

Served in U.S. Army, 1954–56.

Career:

Practiced law in Paris, and began experimental filmmaking,

1956–58; taught at Boston University Law School, 1958–61;

bought rights to

The Cool World

by Warren Miller, and produced documentary version directed by Shirley

Clarke; directed first film,

Titicut Follies

, 1966; received foundation grant to do

High School

, 1967; directed three films funded in part by PBS and WNET Channel 13 in

New York, 1968–71; contracted to make documentaries for WNET,

1971–81; continued to make films for PBS, through 1980s; also

theatre director, late 1980s.

Awards:

Emmy Award, Best Documentary Direction, for

Hospital

, 1970; Peabody Award; Career Achievement Award, International Documentary

Association.

Address:

Zipporah Films, Inc., 1 Richdale Avenue, Suite 4, Cambridge, MA 02140,

U.S.A.

Films as Director, Producer, and Editor:

- 1967

-

Titicut Follies

- 1968

-

High School

- 1969

-

Law and Order

- 1970

-

Hospital

- 1971

-

Basic Training

- 1972

-

Essene

- 1973

-

Juvenile Court

- 1974

-

Primate

- 1975

-

Welfare ; Meat

- 1977

-

Canal Zone

- 1979

-

Sinai Field Mission

- 1980

-

Manoeuvre

- 1981

-

Model

- 1982

-

Seraphita's Diary (+ sc)

- 1983

-

The Store

- 1985

-

Racetrack

- 1986

-

Deaf ; Blind ; Multi-Handicapped ; Adjustment and Work

- 1988

-

Missile

- 1989

-

Near Death

- 1990

-

Central Park

- 1991

-

Aspen

- 1993

-

Zoo

- 1994

-

High School II

- 1995

-

Ballet

- 1996

-

La Comédie Française ou l'amour joue (+ sound)

- 1997

-

Public Housing

- 1999

-

Belfast, Maine

Other Films:

- 1964

-

The Cool World (Clarke) (pr)

- 1968

-

The Thomas Crown Affair (Jewison) (sc, uncredited)

Publications

By WISEMAN: articles—

"The Talk of the Town: New Producer," in New Yorker , 14 September 1963.

Interview with Janet Handelman, in Film Library Quarterly (New York), Summer 1970.

Interview with Ira Halberstadt, in Filmmaker's Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), February 1974.

"Vérités et mensonges du cinéma américain," an interview with M. Martin and others, in Ecran (Paris), September 1976.

"Wiseman on Polemic," an interview with A. T. Sutherland, in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1978.

"Fictions and Other Realities," an interview with J. Gianvito, in International Documentary (Los Angeles), Winter 1990/91.

"Dialogue on Film: Frederick Wiseman," an interview with F. Spotnitz, in American Film, May 1991.

"The Unflinching Eye of Frederick Wiseman," an interview with G. Ferguson, in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), January 1994.

"Revisiting High School: An Interview with Frederick Wiseman," in Cineaste (New York), vol. 20, no. 4, 1994.

On WISEMAN: books—

Issari, M. Ali, Cinema Verité , Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1971.

Maynard, Richard A., The Celluloid Curriculum: How to Use Movies in the Classroom , New York, 1971.

Barsam, Richard, Nonfiction Film: A Critical History , New York, 1973.

Atkins, Thomas, editor, Frederick Wiseman , New York, 1976.

Ellsworth, Liz, Frederick Wiseman: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1979.

Nichols, Bill, Ideology and the Image: Social Representation in the Cinema and Other Media , Bloomington, Indiana, 1981.

Benson, Thomas W., and Carolyn Anderson, Reality Fictions: The Films of Frederick Wiseman , Carbondale, Illinois, 1989.

Grant, Barry Keith, Voyages of Discovery: The Cinema of Frederick Wiseman , Urbana, Illinois, 1992.

On WISEMAN: articles—

Dowd, Nancy, "Popular Conventions," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Spring 1969.

Schickel, Richard, "A Verité View of High School," in Life (New York), 12 September 1969.

Denby, David, "Documentary America," in Atlantic Monthly (Greenwich, Connecticut), March 1970.

Mamber, Stephen, "The New Documentaries of Frederick Wiseman," in Cinema (Beverly Hills), Summer 1970.

Williams, Donald, "Frederick Wiseman," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Fall 1970.

"Frederick Wiseman," in Documentary Explorations , edited by G. Roy Levin, New York, 1971.

Atkins, Thomas, "Frederick Wiseman Documents the Dilemmas of Our Institutions," in Film News (New York), October 1971.

"Frederick Wiseman," in Cinema Verité in America: Studies in Uncontrolled Documentary , by Stephen Mamber, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1974.

Atkins, Thomas, "American Institutions: The Films of Frederick Wiseman," in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1974.

Tuch, R., "Frederick Wiseman's Cinema of Alienation," in Film Library Quarterly (New York), vol. 11, no. 3, 1978.

Nichols, Bill, "Fred Wiseman's Documentaries: Theory and Structure," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Spring 1978.

Le Peron, S., "Fred Wiseman," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), September 1979.

Armstrong, D., "Wiseman's Model and the Documentary Project: Toward a Radical Film Practice," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Winter 1983/84.

Benson, T. W., and C. Anderson, "The Rhetorical Structure of Frederick Wiseman's Model ," in Journal of Film and Video (Los Angeles), vol. 36, no. 4, 1984.

Barsam, R. M., "American Direct Cinema: The Re-presentation of Reality," in Persistence of Vision (Maspeth, New York), Summer 1986.

"Homage," in New Yorker , 20 January 1992.

Pierson, Melissa, "Fly on the Wall," in Vogue (New York), June 1993.

Espen, Hal, "The Documentarians," in New Yorker , 21 March 1994.

Bird, Lance, "Talking Heads: Frederick Wiseman," an interview with Lance Bird, in International Documentary , September 1996.

* * *

In the context of their times, Wiseman's classic documentaries of the 1960s and 1970s are comprehensively anti-traditional. They feature no commentary and no music; their soundtracks carry no more than the sounds Wiseman's recorder encounters; they are long, in some cases over three hours; and, until recent years, they were monochrome. Following the Drew/Leacock "direct cinema" filmmakers, Wiseman developed a shooting technique using lightweight equipment and high-speed film to explore worlds previously inaccessible. In direct cinema the aim was to achieve what they considered to be more honest reportage. Wiseman's insight, however, was to recognise that there is no pure documentary, and that all filmmaking is a process of imposing order on the filmed materials.

For this reason he prefers to call his films "reality fictions." Though he shoots in direct cinema fashion (operating the sound system, in his finest achievements in tandem with cameraman William Brayne), the crucial stage is the imposition of structure during editing. As much as forty hours of film may be reduced to one hour of finished product, an activity he has likened to that of a writer structuring a book. This does not mean that Wiseman's films "tell a story" in any conventional sense. The pattern and meaning of Wiseman's movies seem slowly to emerge from events as if somehow contained within them. Only after seeing the film, perhaps more than once, do the pieces fall into place, their significance becoming clear as part of the whole system of relations that forms the movie. Thus, to take a simple example, the opening shots of the school building in High School make it look like a factory, yet it is only at the end when the school's principal reads out a letter from a former pupil in Vietnam that the significance of the image becomes clear. The soldier is, he says, "only a body doing a job," and the school a factory for producing just such expendable bodies.

Wiseman is not an open polemicist; his films do not appear didactic. But as we are taken from one social encounter to the next, as we are caught up in the leisurely rhythms of public ritual, we steadily become aware of the theme uniting all the films. In exploring American institutions, at home and abroad, Wiseman shows us social order rendered precarious. As he has put it, he demonstrates that "there is a gap between formal and actual practice, between the rules and the way they are applied." What emerges is a powerful vision of people trapped by the ramifications and unanticipated consequences of their own social institutions.

Some critics, while recognising Wiseman's undoubted skill and intelligence, attack him for lack of passion, for not propagandising more overtly. They argue that when he shows us police violence ( Law and Order ), army indoctrination ( Basic Training ), collapsing welfare services ( Welfare ), or animal experiments ( Primate ) he should be more willing to apportion blame and make his commitments clear. But this is to misunderstand his project. Wiseman avoids the easy taking of sides for he is committed to the view that our institutions over-run us in more complex ways than we might imagine. By forcing us to piece together the jigsaw that he offers, he ensures that we understand more profoundly how it is that our institutions can go so terribly wrong. To do that at all is a remarkable achievement. To do it so uncompromisingly over so many years is quite unique.

In the 1980s he sought to broaden his enterprise somewhat. In 1982, for instance, he turned briefly to "fiction," though Seraphita's Diary is hardly orthodox and it is an intelligible extension of his interests. The subsequent documentaries, still produced at regular intervals, have perhaps not had quite the same force as his 1970s work. Central Park , for instance, is hypnotic in the rhythms of daily life that it invokes, but lacks the sheer power of the earlier films, which focused on the often ferocious tensions found in the collision between social institutions and people at the end of their tethers. Nevertheless, he has had a huge influence on the shape of modern documentary filmmaking, and, with Welfare his most compelling achievement, he remains the most sophisticated and intelligent documentarist of postwar cinema.

—Andrew Tudor

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: