A Propos De Nice - Film (Movie) Plot and Review

(On the Subject of Nice)

France, 1930

Director: Jean Vigo

Production: Black and white, 35mm; running time: about 25 minutes. Premiered June 1930, Paris. Filmed winter 1929 through March 1930 in Nice.

Scenario: Mr. and Mrs. Jean Vigo and Mr. and Mrs. Boris Kaufman; photography: Boris Kaufman; editor: Jean Vigo.

Publications

Script:

Vigo, Jean, Oeuvre de cinéma: Films, scénarios, projets de films, texts sur le cinéma , edited by Pierre Lherminier, Paris, 1985.

Books:

Feldman, Harry, and Joseph Feldman, Jean Vigo , London, 1951. Smith, Jean, Jean Vigo , New York, 1971.

Salles-Gomes, P. E., Jean Vigo , Paris 1957; revised edition, Los Angeles, 1971.

Smith, John M., Jean Vigo , New York, 1962.

Lherminier, Pierre, Jean Vigo , Paris, 1967.

Barnouw, Erik, Documentary: A History of the Non-Fiction Film , New York, 1974.

Simon, William G., The Films of Jean Vigo , Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1981.

Salles-Gomes, P.E., Jean Vigo , New York, 1999.

Articles:

Calvalcanti, Alberto, "Jean Vigo," in Cinema Quarterly (Edinburgh), Winter 1935.

Agee, James, "Life and Work of Jean Vigo," in Nation (New York), 12 July 1947.

Weinberg, H. G., "The Films of Jean Vigo," in Cinema (Beverly Hills), July 1947.

Barbarow, George, "The Work of Jean Vigo," in Politics 5 , Winter 1948.

Amengual, Barthélemy, in Positif (Paris), May 1953.

Chardère, Bernard, "Jean Vigo et ses films," in Cinéma (Paris), March 1955.

Mekas, Jonas, "An Interview with Boris Kaufman," in Film Culture (New York), Summer, 1955.

Ashton, Dudley Shaw, "Portrait of Vigo," in Film (London), December 1955.

"Vigo Issue" of Etudes Cinématographiques (Paris), nos. 51–52, 1966.

Beylie, Claude, in Ecran (Paris), July-August 1975.

Liebman, S., in Millenium (New York), Winter 1977–78.

Vigo, Jean, "Towards a Social Cinema," in Millenium (New York), Winter 1977–78.

Travelling (Lausanne), Summer 1979.

Vinnichenko, E., " Po povodu Nitstsy , Frantsiia," in Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), no. 3, 1989.

Sidler, V.,"Traeumer des Kinos, Rimbaud des Films," in Filmbulletin (Winterthur, Switzerland), no. 4, 1992.

* * *

Jean Vigo's reputation as a prodigy of the cinema rests on less than 200 minutes of film. His first venture, a silent documentary 25 minutes long, was A propos de Nice , and in it one can see immediately the energy and aptitude of this great talent. But A propos de Nice is far more than a biographical curio; it is one of the last films to come out of the fertile era of the French avant-garde and it remains one of the best examples to illustrate the blending of formal and social impulses in that epoch.

Confined to Nice on account of the tuberculosis both he and his wife were to die of, Vigo worked for a small company as assistant cameraman. When his father-in-law presented the young couple with a gift of $250, Jean promptly bought his own Debrie camera. In Paris in the summer of 1929 he haunted the ciné-club showings at the Vieux Colombier and at the Studio des Ursulines. There he met Boris Kaufman, a Russian émigré, brother of Dziga Vertov. Kaufman, already an established cameraman in the kino-eye tradition, was enthusiastic about Vigo's plan to make a film on the city of Nice. During the autumn of 1929 Kaufman and his wife labored over a script with the Vigos. From his work Jean began to save ends of film with which to load the Debrie and by year's end the filming was underway.

Originally planned as a variant of the city symphony, broken into its three movements (sea, land, and sky) A propos de Nice was destined to vibrate with more political energy than did Berlin, Rien que les heures, Manhattan , or any of the other examples of this type. From the first, Vigo insisted that the travelogue approach be avoided. He wanted to pit the boredom of the upper classes at the shore and in the casinos against the struggle for life and death in the city's poorer backstreets.

The clarity of the script was soon abandoned. Unable to shoot "live" in the casinos and happy to follow the lead of their rushes, Vigo and Kaufman concentrated on the strength of particular images rather than on the continuity of a larger design. They were certain that design must emerge in the charged images themselves, which they could juxtapose in editing.

The power of the images derives from two sources, their clearcut iconographic significance as social documents, and the high quality they enjoy as photographs, carefully (though not artfully) composed. Opposition is the ruling logic behind both these sources as they appear in the finished film, so that pictures of hotels, lounging women, wealthy tourists, and fancy roulette tables are cut against images of tenements, decrepit children, garbage, and local forms of back-street gambling. In the carnival sequence which ends the film, the power bursting within the city's belly spills out onto the streets of the wealthy and dramatizes a conflict which geography can't hide.

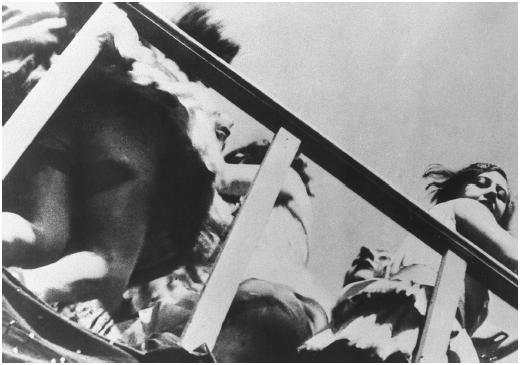

Formally the film opposes a two-dimensional optical schema, used primarily for the wealthy parts of town, to a tactile, nearly 3-D approach. Aerial shots and the voyeurism of the "Promenade des Anglais" define the wealthy as indolent observers of sports, while deep in the town itself everyone, including the camera, participates in the carnal dance of life, a dance whose eroticism is made explicit toward the film's end.

Entranced by Surrealism (at the premiere of this film Vigo paid homage to Luis Buñuel), the filmmakers used shock cuts, juxtaposing symbolic images like smokestacks and Baroque cemeteries. A woman is stripped by a stop-action cut and a man becomes a lobster. Swift tilts topple a grand hotel. As he proclaimed in his address, this was to be a film with a documentary point of view. To him that meant hiding the camera to capture the look of things (Kaufman was pushed in a wheelchair along the Promenade cranking away under his blanket), and then editing what they collected to their own designs.

A propos de Nice is a messy film. Full of experimental techniques and frequently clumsy camerawork, it nevertheless exudes the energy of its creators and blares forth a message about social life. The city is built on indolence and gambling and ultimately on death, as its crazy cemetery announces. But underneath this is an erotic force that comes from the lower class, the force of seething life that one can smell in garbage and that Vigo uses to drive his film. A propos de Nice advanced the cinema not because it gave Vigo his start and not because it is a thoughtfully made art film. It remains one of those few examples where several powers of the medium (as recorder, organizer, clarifier of issues, and proselytizer) come together with a strength and ingenuity that are irrespressible. The critics at its premiere in June 1930 were impressed and Vigo's talent was generally recognized. But the film got little distribution; the age of silent films, even experimental ones like this, was coming to an end. This is too bad. Every director should begin his or her career as Vigo did, with commitment, independence, and a sense of enthusiastic exploration.

—Dudley Andrew

J.W.