Andrei Rublev - Film (Movie) Plot and Review

USSR, 1969

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

Production: Mosfilm Studio (Moscow); black and white with a color sequence, 35mm, Cinemascope; running time: 185 minutes; length: 5180 meters. Released 1969 in France; not released in USSR until 1972 though the film had been screened in Moscow in 1965. The film was censored and re-edited (not by Tarkovsky) several times between production and release in 1969. Filmed 1965.

Screenplay: Andrei Mikhalkov-Konchalovsky and Andrei Tarkovsky; photography: Vadim Youssov; editors: N. Beliaeva and L. Lararev; sound: E. Zelentsova; production designer: Eugueni Tcheriaiev; music: Viatcheslac Ovtchinnikov.

Cast: Anatoli Solonitzine ( Rubliov ); Ivan Lapikov ( Dirill ); Nikolai Grinko ( Daniel the Black ); Nikolai Sergueiev ( Theophanes the Greek ); Irma Raouch Tarkovskaya ( Deaf-mute ); Nikolai Bourliaiev ( Boriska ); Youri Nasarov ( Grand Duke ); Rolan Bykov ( Buffoon ); Youri Nikulin ( Patrikey ); Mikhail Kononov ( Fomka ); S. Krylov; Sos Sarkissyan; Bolot Eichelanev; N. Grabbe; B. Beijenaliev; B. Matisik; A. Oboukhov; Volodia Titov.

Awards: Cannes Film Festival, International Critics Award, 1969.

Publications

Script:

Tarkovsky, Andrei, Andrei Rublev , Paris, 1970.

Books:

Vronskaya, Jeanne, Young Soviet Film Makers , London, 1972.

Cohen, Louis H., The Cultural-Political Traditions and Development of the Soviet Cinema: 1917–1972 , New York, 1974.

Stoil, Michael Jon, Cinema Beyond the Danube: The Camera and Politics , Metuchen, New Jersey, 1974.

Liehm, Mira and Antonin, The Most Important Art: East European Film after 1945 , Berkeley, 1977.

Tarkovsky, Andrei, Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema , London, 1986.

Borin, Fabrizio, Andrej Tarkovskij , Venice, 1987.

Jacobsen, Wolfgang, and others, Andrej Tarkovskij , Munich, 1987.

Le Fanu, Mark, The Cinema of Andrei Tarkovsky , New York, 1987.

Johnson, Vida T., and Graham Petrie, The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue , Bloomington, Indiana, 1994.

Goldenberg, Mikhail, V Glubinakh Sudeb Lyudskikh—In the Depths of Destinies , Baltimore, 1999.

Andrei Tarkovsky: Collected Screenplays , London, 1999.

Articles:

Gregor, U., "Schwierigkeiten beim Filmen de Geschichte," Kinemathek (Germany), no. 41, July 1969.

Lebedewa, J.A., "Andrej Rubljow und seine Zeit," Kinemathek (Germany), no. 41, July 1969.

Tarkovsky, A. "Die bewahrte Zeit," Kinemathek (Germany), no. 41, July 1969.

Vronskaya, Jeanne, in Monogram (London), Summer 1971.

Wiersewski, W., "Artysta na gościńcu epoki: Andrej Rublow ," in Kino (Warsaw), November 1972.

"Andre Rubliov Issue" of Filmrutan (Sweden), no. 2, 1973.

Povše, J., " Andrej Rublov —film projekcije po projekciji," in Ekran (Ljubljana, Yugoslavia), no. 108–110, 1973.

Cetinjski, M., in Ekran (Ljubljana, Yugoslavia), no. 194–195, 1973.

Amengual, B., "Allégori et Stalinisme dans quelques films de l'est," in Positif (Paris), January 1973.

Gerasimov, Sergei, and others, in Filmkultura (Budapest), March-April 1973.

Montagu, Ivor, "Man and Experience: Tarkovsky's World," in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1973.

Tarrat, M., in Films and Filming (London), November 1973.

O'Hara, J., in Cinema Papers (Australia), 1975.

Grande, M., in Filmcritica (Rome), January-February 1976.

Rineldi, G., in Cineforum (Bergamo), January-February 1976.

Prono, F., in Cinema Nuovo (Turin), March-April 1976.

Chapier, Henry, in Cambat (Paris), 20 November 1979, excerpt reprinted in Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris) 15 December 1979.

Ciment, Michel, "Richesse et diversité du nouveau cinéma soviétique," in Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), 15 December 1979.

Ward, M., "The Idea that Torments and Exhausts," in Stills (London), Spring 1981.

Torp Pedersen, B., in Filmrutan (Stockholm), 1984.

van der Kaap, H., and G. Zuilhof, in Skrien (Amsterdam), Summer 1985.

Anninskii, L., "Popytka ochishcheniia?" in Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), no. 1, 1989.

Illg, E., and L. Noiger, "Vstat' na lut'," in Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), no. 2, 1989.

"Tarkovskijs rad till blivande kolleger," in Chaplin (Stockholm), no. 4, 1989.

Vinokurova, T., "Khozhdenie po mukam Andreiia Rubleva ," in Iskusstvo Kino (Moscow), no. 10, 1989.

Pistoia, M., "Elogio del piano-sequenza," in Filmcritica (Rome), January-February 1991.

Strick, P., "Releasing the Balloon, Raising the Bell," in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), February 1991.

Giavarini, L., " Andrei Roublev , un film de Russie," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), December 1991.

Bleeckere, Sylvain De, "De religiositeit van de beeldcultuur: Tarkovsky and Andrei Roeblev," Film en Televisie + Video (Brussels), February 1992.

Kovacs, A. B., "Tarkovszkij szellimi utja," in Filmvilag (Budapest), no. 12, 1992.

Leutrat, J.-L., "Considerations intempestives autour d' Andrei Roublev ," in Positif (Paris), April 1992.

Meeus, M. "De passie van Andrei," Film en Televisie + Video (Brussels), September 1994.

Elrick, Ted, "The Prince, the Kid, and the Painter," DGA Magazine (Los Angeles), vol. 20, no. 2, April/May 1995.

Schillaci, F., "Lo spazio il tempo nell'opera di Andrej Tarkovskij," Spettacolo , vol. 46, no. 1, 1996.

Wiese, I. "Andrej Tarkovskij," Z (Oslo), no. 1, 1996.

"Nel giusto mezzo: Andrej Rublev ," Castoro Cinema (Milan), no. 181, January/February 1997.

* * *

Andrei Tarkovsky's second feature film did not have an easy passage. Conceived and written in the early 1960s and completed in 1966, it finally arrived at Cannes, where it was awarded the International Critics Prize, in 1969. It did not surface in Soviet cinemas until 1972, after the authorities there had attacked it as unhistorical and narratively obscure, and had raised objections to its level of violence. To Western eyes, this attempt to muzzle and belittle what was so obviously a monumental work reeked of pre-perestroika censorship, and epitomized the typical muddle-headedness of the cultural dogma of socialist realism. However, as Ivor Montagu, erstwhile collaborator with Eisenstein, observed in the British Magazine, Sight and Sound , not many European or American directors are given the opportunity to make "colour, widescreen, 3" hour superproductions" about the intimate life of medieval monks. Although Tarkovsky did remove 14 minutes from his original version, he professed himself

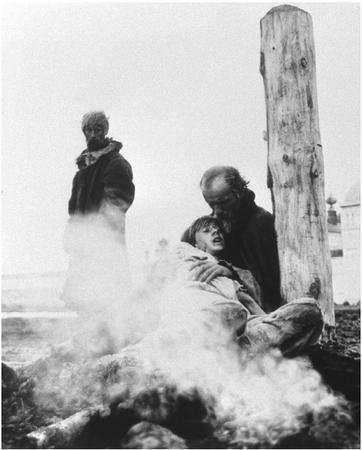

Andrei Rublev was co-scripted by Tarkovsky's fellow Moscow film school graduate, Konchalovsky, and photographed by Vadim Youssov, Tarkovsky's trusted cameraman until he refused to work on Mirror (1974), claiming that the director's script was self-indulgent and unintelligible. Andrei Rublev charts seven episodes in the life of its eponymous hero, an artist and monk who, from the cocooned seclusion of a monastery, is exposed to the horrors of the 15th-century world. In a magical mystery tour, Rublev is confronted with brutality, torture, drunkenness, tartar despoliation, rape, pillage, and famine, but manages to maintain his faith in humanity. Inspired by a young waif, Boriska (played by Nikolai Bourliaiev, the protagonist in Ivan's Childhood , Tarkovsky's first feature, made in 1962), who assumes responsibility for the making of a huge bell, finding and moulding the clay, requisitioning the silver, supervising a veritable army of older and more experienced assistants, all the time aware that if the bell fails to chime he will be put to death by the arch-duke, Rublev learns that, in the midst of social upheaval and wholesale destruction, creativity is still possible.

Perhaps the aspect of Andrei Rublev that most irritated Soviet authorities was its religious iconography. Rublev, being a monk, is necessarily Christian. For Tarkovsky, who as a film director seems to have identified closely with the icon painter, Rublev's creativity and his faith are inextricable: the former is merely the embodiment of the latter. Creativity is not about character or milieu or means of production. In the film it is presented as a mystical transcendent force that must, nonetheless, take into account the exterior world. Throughout the film, counterpointing Rublev and acting as his foil, is a fellow artist, Theophanes the Greek. Theophanes witnesses the same medieval maelstrom as Rublev, but reacts to it in a very different way. Whereas Rublev overcomes his revulsion, and is able to forgive and even to love humanity, Theophanes feels nothing but disgust. He sees human kind as base and fallen, and tries to immure himself. In his isolation, he is the inferior artist.

The film is not an historical record. There are few details extant of Andrei Rublev's life. Tarkovsky and Konchalovsky offer him materiality, a psychology, and an ability to bear witness to his own epoch. And from the virtuoso opening crane-shots, showing a medieval hot-air balloonist, to the tartars' razing of the cathedral, to frenzied pagan ritual, to all the palaver of the building of an enormous bell, Andrei Rublev is on an epic scale. Tarkovsky shows an unerring instinct for filming landscape, for filming the elements. His vision of the middle ages does not seem to allow for the possibility of sunshine; on his grim backcloth, wind and rain are pretty well constant. There is plenty of mud and water in which characters can get stuck, and blood is forever being spilled. There is nothing coy or cosmetic about Tarkovsky's imagined world, nothing too rarefield: this is visceral and violent terrain. Horses—Tarkovsky, like Kurosawa, is an expert at photographing the beasts—gallop up and down the landscape to great effect. Anatoli Solonitzine, Tarkovsky's favourite actor, plays Rublev with quiet and stoical dignity. But Rublev is so impassive and austere a figure, and so taciturn, that it is hard to have much sympathy for him. Though Tarkovsky always claimed that Dovzhenko was the Soviet director he felt most affinity with, Andrei Rublev echoes Eisenstein's Ivan the Terrible and Alexander Nevsky , both in its grandiose reconstruction of a period in Russian history, and in its facility in depicting battle scenes and dealing with crowds.

The jerky jumps between episodes, often shooting us forward a matter of years in an instant, are somewhat bewildering. Tarkovsky's disdain for linear narrative, which he likens to the proof of a geometrical theorem, is well charted. He defended Andrei Rublev from the charge of obscurity by citing Engels, who claimed that the more sophisticated the work, the more intricate was its use of formal device. However, Andrei Rublev does not have the multi-layered narrative of, for example, Mirror , which shifts easily from generation to generation, and from place to place. Three hours of saturnine medieval gloom, even if relieved by a gallery of wonderfully grotesque Breughelian physiognomies, is hard to take. Nonetheless, as a rigorous meditation on faith, art, and creation in a time of fratricide and civil strife, as a moral fable, and as a bravura piece of filmmaking, Andrei Rublev is magnificent.

The film, which has been in black and white, ends with a tremendous explosion of colour as we finally see images of Rublev's celebrated icons, in particular his Trinity , which is to be found at the Trinity-St. Sergius monastery in Zagorsk. These paintings, beautiful and abstracted from the world in which they were created, are the film's justification. Out of degradation, murder, carnage, out of the turbulent landscape of 15th-century Russia, ungodly, riven by civil war, Rublev is able to create sublime and timeless works of art.

—G. C. Macnab

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: