La DentelliÈre - Film (Movie) Plot and Review

(The Lacemaker)

Switzerland-France-West Germany, 1977

Director: Claude Goretta

Production: Citel Films (Geneva), Actions Films (Paris), and Filmproduktion (Frankfort); Eastmancolor, 35mm; running time: 108 minutes. Released May 1977, France. Filmed in France.

Producer: Yves Peyrot with Yves Gosser; screenplay: Claude Goretta and Pascal Laine, from the novel by Laine; photography: Jean Boffety; editor: Joelle Van Effenterre; sound: Pierre Gemet and Bernard Chaumeil; production design: Serge Etter and Claude Chevant; music: Pierre Jansen; music editor: Georges Bacri.

Cast: Isabelle Huppert ( Béatrice ); Yves Beneyton ( François ); Florence Giorgietti ( Marylène ); Anne-Marie Duringer ( Béatrice's mother ); Jean Obe ( François' father ); Monique Chaumette ( François' mother ); Michel de Re ( The Painter ); Renata Schroeter ( Francois' friend ); Sabine Azema ( Student ).

Awards: Cannes Film Festival, Ecumenical Prize, 1977.

Publications

Script:

Goretta, Claude, and Pascal Laine, La Dentellière , Paris, 1981.

Articles:

Moskowitz, G., Variety (New York), 25 May 1977.

Roulet, C., in Cinématographe (Paris), June 1977.

Maillet, D., "Claude Goretta," in Cinématographe (Paris), June 1977.

Jong, A., "Claude Goretta en La Dentellière ," in Skoop (Amsterdam), June-July 1977.

Chevassu, F., in Image et Son (Paris), September 1977.

Milne, Tom, in Monthly Film Bulletin (London), November 1977.

International Film Guide 1978 , London, 1978.

Leroux, A., in Séquences (Montreal), January 1978.

Pruks, I., in Cinema Papers (Melbourne), April-June 1978.

Peterson-Schultz, B., in Kosmorama (Copenhagen), Summer 1978.

Kass, Judith, "Claude Goretta and Isabelle Huppert," in Movietone News (Seattle), 14 August 1978.

Parker, G., in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Fall 1978.

Günter, J., in Film und Fernsehen (Berlin), October 1978.

Brossard, Jean-Pierre, "Trotz allem hoofe ich," in Film und Fernsehen (Berlin), October 1978.

Termino, L., in Cinema Nuovo (Bari), February 1980.

Cèbe, Gilles, "Une Martyre de l'amour," in Avant-Scène du Cinéma (Paris), 15 April 1981.

Millar, Gavin, in Listener (London), 3 March 1983.

Télérama (Paris), 6 November 1996.

* * *

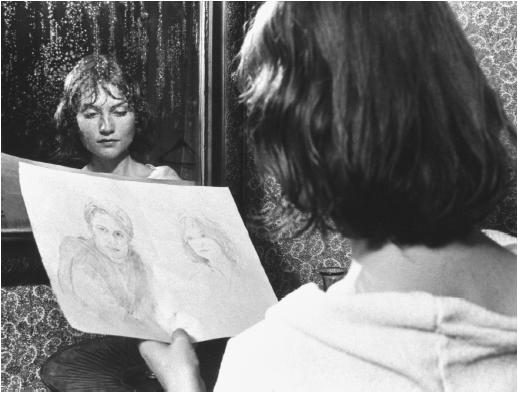

Claude Goretta's third feature film, his first made in France, tells a deceptively simple story of lost innocence against the picturesque background of the Normandy coast and the contemporary ambience of Paris. The Lacemaker is marked by the economy, close observations, and compassion of its director and the virtuoso performance of its star, Isabelle Huppert, who plays Béatrice, nicknamed "Pomme," a shy young assistant in a Paris beauty parlor. The film depicts her first romance with a well-bred Sorbonne student named François (Yves Beneyton), who meets her while on vacation in the resort town of Cabourg and rejects her some months later, bringing on an emotional and physical collapse. Goretta has synthesized several potentially sentimental genres— Bildungsroman , pastoral, seduction story, poor-meets-rich romance—and managed to evoke fresh responses to his film's own particular time and place.

The Lacemaker begins by exploring the friendship between Pomme and Marylène (Florence Giorgietti), a slightly older and far more

Marylène soon meets a new man and moves out of the hotel room she briefly shared with Pomme, who acquiesces silently. François sees her eating an ice cream at an outdoor cafe and introduces himself to the shy girl as a brilliant student of literature from Paris. Goretta departs from his customary unobtrusive cinematic style at this point with a beautiful sequence of long tracking shots and cross-cutting to depict François and Pomme looking for each other the next day. The distance between them in the panoramic vistas and the high camera placements suggest both the separate worlds they inhabit and the fate that draws them together. When they finally meet on the boardwalk, Pomme wears a white dress and François a dark t-shirt and jeans, visually underscoring their differences at the very moment their romance begins.

Goretta depicts the development of their relationship through a series of delicately woven vignettes, the most clearly symbolic of which involves a game of blindman's bluff on a steep cliff overlooking the Channel. François leads her to the very edge, but Pomme continues to follow his commands without ever opening her eyes. When she finally does, standing at the very edge of the precipice, François has to grab her to keep her from falling with fright. Soon after this strangely disturbing interlude, Pomme agrees to sleep with him, her first time with a man.

Back in Paris and now living in François's flat near the university, Pomme happily cleans and cooks after her own work at the beauty parlor is done so that he might pursue his studies. Their life together seems epitomized in a scene where she tries to eat an apple silently (her nickname, "pomme," means "apple") without disturbing his concentration, and he becomes annoyed not so much by the sound as by her effort at self-effacement. The film's pivotal scene occurs during the couple's visit with François's parents in the country. When the dinner conversation turns to news about François's successful young friends and questions about what she does for a living, Pomme is overcome by a violent fit of choking. In moments such as these, Goretta reveals the subtle unraveling of their romance, without a single argument between them. In a high-angle long shot foreshadowing their parting, and mirroring the panoramic views of Cabourg, François rushes across a city boulevard, leaving Béatrice stranded on a traffic island. Some time after François explains how breaking up will be best for both of them and returns her to her mother's apartment, Béatrice collapses in the middle of a busy intersection.

The Lacemaker's final sequence takes place in a sanatorium where François comes to visit Béatrice, whose altered appearance is profoundly disquieting. She wears a shapeless black dress like a shroud; she moves and speaks mechanically, drained of all her former charm. As they pass the time together in a park filled with fallen yellow leaves, François asks what she has been doing since they parted. When Béatrice tonelessly describes a trip to Greece with someone she met, François seems relieved to learn she has taken other lovers. In the closing shot, however, the camera tracks in on the therapy room where Béatrice sits alone in a corner knitting in front of a bright poster of Mykonos. Her foreign travel was an illusion, both a deception and farewell gift for the guilt-ridden François. As the truth dawns, she turns to the camera with a chilling expression which Goretta then freezes. The closing title appears, with its reference to the anonymous working women—seamstresses, water-girls, lacemakers—of the paintings of the Old Masters.

Goretta's film, like his heroine's face, is deceptively simple. While seemingly inviting interpretation as a modern parable of innocence betrayed, a Marxist allegory on the plight of the working class, feminist tract against patriarchal society, or even a clinical study of mental breakdown, The Lacemaker remains ultimately less moralistic than Eric Rohmer's films, less political than Godard's or Tanner's, less intellectual than Resnais's. Goretta's deepest concern— and the film's ultimate "meaning"—lies with Béatrice herself, with what she has lost and, just possibly, what she has gained.

—Lloyd Michaels

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: