ERASERHEAD - Film (Movie) Plot and Review

USA, 1976

Director: David Lynch

Production: David Lynch, AFI Centre for Advanced Film Studies; black and white, 16mm; running time: 89 minutes. Filmed in Los Angeles, 1971–76.

Producer: David Lynch; screenplay: David Lynch; photography: Frederick Elmes, Herbert Cardwell; editor: David Lynch; production designer: David Lynch; sound: Alan Splet; special effects: David Lynch; special photographic effects: Frederick Elmes; art director: Jack Fisk.

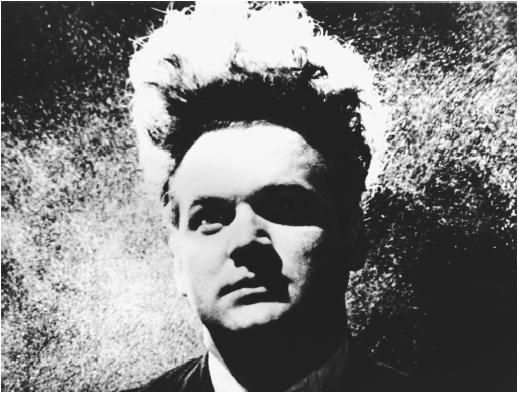

Cast: Jack Nance ( Henry Spencer ); Charlotte Stewart ( Mary ); Allan Joseph ( Bill ); Jeanne Bates ( Mary's mother ).

Publications

Books:

Peary, Danny, Cult Movies , New York, 1983.

Hoberman, J., and Jonathan Rosenbaum, Midnight Movies , New York, 1983.

Samuels, Stuart, Midnight Movies , New York, 1983.

Kaleta, Kenneth, David Lynch , New York, 1992.

Alexander, John, The Films of David Lynch , London, 1993.

Lynch, David, Images , New York, 1994.

Chion, Michel, David Lynch , Bloomington, 1995.

Nochimson, Martha P., The Passion of David Lynch , Austin, 1997.

Woods, Paul A., Weirdsville U.S.A. , London, 1997.

Rodley, Chris, Lynch on Lynch , New York, 1999.

Articles:

Variety (New York), 23 March 1977.

Taylor, D., Monthly Film Bulletin (London), March 1979.

Braun, E., Films and Filming (London), April 1979.

Island, Russ, Cinemonkey (Portland, Oregon), Spring 1979.

Rosenbaum, J., "Eraserhead à New York," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), April 1981.

Godwin, K. George, "Eraserhead: The Story behind the Strangest Film Ever Made and the Cinematic Genius Who Directed It," in Cinefantastique (New York), September 1984.

Angst, W., "David Lynch," in Dark Movies , no. 6, 1989.

Breskin, David, "The Rolling Stone Interview with David Lynch," in Rolling Stone , no. 586, 6 September 1990.

Thomas, J.D., "A Divide Erased," in Village Voice (New York), 7 June 1994.

Ostria, V., in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), July/August 1994.

Satuloff, Bob, "Movie Memories," in Christopher Street , no. 225, May 1995.

Landrot, Marine, "Le maître d'immonde: Eraserhead ," in Télérama (Paris), 18 October 1995.

Poussu, Tarmo, in Filmihullu (Helsinki), no. 4–5, 1997.

* * *

In Midnight Movies , which devotes an entire chapter to Eraserhead , Jonathan Rosenbaum and J. Hoberman describe David Lynch's first feature as "an intellectual splatter film-cum-thirty-five-millimetre nightmare sitcom of the urban soul." Significantly, mainly through footnotes, Rosenbaum and Hoberman qualify their account of the film as art work and cult case history with hints that neither of them like it all that much. In a "Personal View" accompanying a retrospective piece in Cinefantastique , K. George Godwin compares Eraserhead with the archetypal midnight cult movie, Jim Sharman's The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975):

They [the audience] come to laugh, to talk back at the screen, to participate. As the film begins, they are loud, jeering, laughing at any and everything . . . but as it progresses, the laughter thins, becomes more nervous and defensive. The film, for all of its weird humour, is not funny; it is strange, and its strangeness is of an unfamiliar kind. There is something uniquely disturbing about it, something which works even on those who have not come to take it seriously. Unlike Sharman's film, Eraserhead steadfastly refuses to provide a communal experience . . . somehow it instead isolates the individual viewer, absorbs him into a nightmare of personal experience. Seeing Eraserhead is an unshared experience: it is as if the film plays not on the screen but inside one's own head.

Lynch is an American original, committed enough to his own vision to wagon-master Eraserhead through nearly seven years of low-budget production, persuading collaborators to endure severe hardships (actor Jack Nance sported his character's Bride of Frankenstein quiff year after year as shooting continued) in the service of the end product. Eraserhead seems a free-form nightmare, but it has a tight narrative and strains for extreme technical sophistication. Asked what inspired the film, Lynch, in typically reductive fashion, has cited Philadelphia, where he lived in a bad neighbourhood for a while. The urban nightmare, weighed down by alienation and physical disgust, is played out in dingy apartments whose windows afford views of brick walls, with few ventures out onto grimy industrial streets and occasional fantastic plunges into a vaudeville dreamland behind a hissing radiator. Henry Spencer (Nance), who adopts Lynch's trademark blank stare, is on vacation from his job and finds himself drawn back into a relationship with Mary X (Charlotte Stewart), who invites him to her family apartment for a hideous

Of all the underground artist-turned-filmmakers, Lynch is the one who can also function as a Hollywood (or even television) professional: Eraserhead was "written, produced, and directed" by its auteur. The film probes unhealthy spots and nightmare extremes but does so with a steady, professional fascination that refuses to be classed as trash: no Warholian letting the camera run on and on without caring what's in front of it, no Kuchar Brothers home movie melodrama, no John Waters-ish community panto production values and strident amateur performances, no George Romero reliance on the conventions and concerns of low-rent horror films. These directors and their collaborators, let alone other painter-cum-filmmakers like Derek Jarman, Michael Snow, or Peter Greenaway, have never risked Academy Award nominations while Lynch (a Best Director nominee for The Elephant Man ) and several of his crew—art director Fisk, sound designer Alan Splet (who won an Oscar for his work on The Black Stallion , 1979), even set decorator Sissy Spacek—have secured resident alien status in Hollywood.

Eraserhead is remarkably concentrated and consumed with disgust for the physical, free-associating weirdness as it plays out the grimy anecdote of Henry's entrapment, destruction, and (perhaps) redemption. In subsequent work, from The Elephant Man (1980), through Dune (1984), Blue Velvet (1986), Wild at Heart (1990), and the Twin Peaks TV series and movie, Lynch would adopt a more mainstream disguise for his concerns, adding character (especially in The Elephant Man ), colour (especially in Blue Velvet ), and almost-warm wit (especially in Twin Peaks ), increasingly embracing the trappings of popular culture (music, B movies, soap opera, horror films, pretty stars). Here, working in isolation from commercial cinema, he was either less compromizing or more recalcitrant, creating a work of slick strangeness which remains the dark heart of his developing oeuvre and whose almost subliminal artistic (and political) conservatism perhaps explains its lasting cult success. Withal, it remains—unlike much of Lynch's later films—a work of genius it is impossible to love, so personal for its makers and its individual audience members that its many admirable or astonishing features still don't make it a film whose world one cares to revisit at all often.

—Kim Newman

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: