FANTASIA - Film (Movie) Plot and Review

USA, 1940

Story Directors: Joe Grant and Ben Sharpsteen

Production: Walt Disney Productions; Technicolor, 35mm, animation, Fantasound; running time: 126 minutes, British version cut to 105 minutes, later versions cut to 81 minutes; length: originally 11,361 feet, cut to 9405 feet for British version. Released 13 November 1940 by RKO/Radio. Re-released every 5–7 years, beginning in 1946. Re-released in 1982 with soundtrack in digital audio. Filmed in Walt Disney Studios. Cost: $2,280,000.

Producer: Walt Disney; story developers: Lee Blair, Elmer Plummer, and Phil Dike ("Toccata and Fugue in D Minor" episode); Sylvia Moberly-Holland, Norman Wright, Albert Heath, Bianca Majolie, and Grahm Heid ("The Nutcracker Suite" segment); Perce Pearce and Carl Fallberg ("The Sorcerer's Apprentice" segment); William Martin, Leo Thiele, Robert Sterner, and John Fraser McLeish ("The Rite of Spring" segment); Otto Englander, Webb Smith, Erdman Penner, Joseph Sabo, Bill Peet, and George Stallings ("Pastoral Symphony"); Martin Provensen, James Bodrero, Duke Russell, and Earl Hurd ("Dance of the Hours"); Campbell Grant, Arthur Heinemann, and Phil Dike ("Night on Bald Mountain/Ave Maria" segment); directors: Samuel Armstrong ("Toccata and Fugue in D Minor" and "The Nutcracker Suite" segments); James Algar ("The Sorcerer's Apprentice" segment); Bill Roberts and Paul Satterfield ("The Rite of Spring" segment); Hamilton Luske, Jim Hangley, and Ford Beebe ("Pastoral Symphony"); T. Hee and Norman Ferguson ("Dance of the Hours" segment); Wilfred Jackson ("Night on Bald Mountain/Ave Maria" segment); animation directors: Samuel Armstrong ("Toccata and Fugue in D Minor" and "The Nutcracker Suite"); Bill Roberts ("The Rite of Spring"); James Algar ("The Sorcerer's Apprentice"); Hamilton Luske, Jim Handley and Ford Beebe ("Pastoral Symphony"); T. Hee and Norman Ferguson ("Dance of the Hours"); and Wilfred Jackson ("Night on Bald Mountain/Ave Maria"); musical film editor: Stephen Csillag; sound and music recordists: William E. Garity, C. O. Slyfield, and J. N. A. Hawkins; sound system, called Fantasound, designed especially for the film; art directors: Robert Cormack ("Toccata and Fugue in D Minor" segment); Robert Cormack, Al Zinnen, Curtiss D. Perkins, Arthur Byram, and Bruce Bushman ("The Nutcracker Suite" segment); Tom Codrick, Charles Phillippi, and Zack Schwartz ("The Sorcerer's Apprentice" segment); McLaren Stewart, Dick Kelsey, and John Hubley ("The Rite of Spring" segment); Hugh Hennesy, Kenneth Anderson, J. Gordon Legg, Herbert Ryman, Yale Gracey, and Lance Nolley ("Pastoral Symphony" segment); Kendall O'Connor, Harold Doughty, and Ernest Nordli ("Dance of the Hours" segment); Kay Nielson, Terrell Stapp, Charles Payzant and Thor Putnam ("Night on Bald Mountain/Ave Maria" segment); music director: Edward H. Plumb; music conductor: Leopold Tokowski (Irwin Kostal for 1982 release); music: selections include Bach's "Toccata and Fugue in D Minor"; Tchaikovsky's "The Nutcracker Suite"; Dukas' "The Sorcerer's Apprentice"; Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring"; Beethoven's "Pastoral Symphony"; Ponchielli's "Dance of the Hours"; Mussorgsky's "Night on Bald Mountain"; and Schubert's "Ave Maria"; special animation effects: Joshua Meador, Miles E. Pike, John F. Reed, and Daniel Leonard Pickely; animation

Cast: Deems Taylor ( Narrative Introductions ).

Awards: New York Film Critics' Special Award, 1940; Oscars, Special Awards (certificates), to Walt Disney, William Garity, John N. A. Hawkins, and RCA for Contributions to the Advancement of Sound in Motion Pictures, 1941; Oscar, Special Award (certificate), to Leopold Stokowski for his Achievement in the Creation of a New Form of Visualized Music, 1941.

Publications

Books:

Taylor, Deems, Walt Disney's Fantasia , New York, 1940.

Field, Robert D., The Art of Walt Disney , New York, 1942.

Manvell, Robert, and J. Huntley, The Technique of Film Music , New York, 1957.

Stevenson, Ralph, Animation in the Cinema , New York, 1967.

Schickel, Richard, The Disney Version: The Life, Times, Art, and Commerce of Walt Disney , New York, 1968; revised edition, 1986.

Bessy, Maurice, Walt Disney , Paris, 1970.

Finch, Christopher, The Art of Walt Disney: From Mickey Mouse to the Magic Kingdoms , New York, 1973; revised edition, 1999.

Maltin, Leonard, The Disney Films , New York, 1973; revised edition, 1984, 2000.

Thomas, Bob, Walt Disney: An American Original , New York, 1976.

Edera, Bruno, Full-length Animated Features , edited by John Halas, New York, 1977.

Leebron, Elizabeth, and Lynn Gartley, Walt Disney: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1979.

Thomas, Frank, and Ollie Johnston, Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life , New York, 1982.

Culhane, John, Walt Disney's Fantasia , New York, 1983.

Bruno, Eduardo, and Enrico Ghezzi, Walt Disney , Venice, 1985.

Mosley, Leonard, Disney's World: A Biography , New York, 1985; as The Real Walt Disney , London, 1986.

Culhane, Seamus, Talking Animals and Other People , New York, 1986.

Thomas, Frank, and Ollie Johnston, Too Funny for Words: Disney's Greatest Sight Gags , New York, 1987; revised edition 1999.

Grant, John, Encyclopedia of Walt Disney's Animated Characters: From Mickey Mouse to Hercules , New York, 1998.

Thomas, Bob, Building a Company: Roy O. Disney and the Creation of an Entertainment Empire , New York, 1998.

Smith, Dave, Disney A to Z: The Updated Official Encyclopedia , New York, 1999.

Solomon, Charles, The Art of Disney , New York, 2000.

Articles:

Variety (New York), 21 August 1940.

Robins, S., "Disney Again Tries Trailblazing," in New York Times Magazine , 3 November 1940.

Variety (New York), 13 November 1940.

New York Times , 14 November 1940.

Time (New York), 18 November 1940.

Hollering, F., in Nation (New York), 23 November 1940.

Ferguson, O., in New Republic (New York), 25 November 1940.

Hartung, P. T., in Commonweal (New York), 29 November 1940.

Gessner, Robert, "Class in Fantasia ," in Nation (New York), 30 November 1940.

Hollister, P., "Walt Disney, Genius at Work," in Atlantic (Boston), December 1940.

Isaacs, H. R., in Theatre Arts (New York), January 1941.

Peck, A. P., "What Makes Fantasia Click?," in Scientific American (New York), January 1941.

Boone, Andrew R., "Mickey Mouse Goes Classical," in Popular Science Monthly (New York), January 1941.

Haggin, B. H., in Nation (New York), 11 January 1941.

Iwerks, Ub, in Popular Mechanics (New York), January 1942.

Ericsson, Peter, "Walt Disney," in Sequence (London), no. 10, 1950.

Fallberg, Carl, "Animated Film Technique" (series of nine articles), in American Cinematographer (Los Angeles), July 1958 through March 1959.

Hicks, Jimmie, in Films in Review (New York), November 1965.

Zinsser, W., "Walt Disney's Psychedelic Fantasia ," in Life (New York), 3 April 1970.

"Disney Issue" of Kosmorama (Copenhagen), November 1973.

Moritz, W., "Fischiner at Disney; or, Oscar in the Mousetrap," in Millimeter (New York), February 1977.

Paul, William, "Art, Music, Nature, and Walt Disney," in Movie (London), Spring 1977.

Canemaker, J., "Disney Animation: History and Technique," in Film News (New York), January-February 1979.

Canemaker, J., in Millimeter (New York), February 1979.

Coleman, John, in New Statesman (London), 30 March 1979.

Stuart, A., in Films and Filming (London), April 1979.

Andrault, J. M., in Revue du Cinéma (Paris), November 1979.

Prouty, Howard H., in Magill's Survey of Cinema 2 , Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1980.

Starburst (London), vol. 3, no. 2, 1980.

Mallow, S., "Lens Cap: Finding Fantasia ," in Filmmakers Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), March 1980.

Braun, E., in Films (London), August 1982.

Soundtrack! (Los Angeles), September 1982.

Adler, Dick, "Hippo's Revenge: A Behind-the-Cels Look at Fantasia on the 50th Anniversary of What They Called Walt's Folly," in Los Angeles Magazine , September 1990.

Adler, Dick, "The Fantasy of Disney's Fantasia ," in Chicago Tribune , 23 September 1990.

Alexander, M., "Disney Sweeps the Dust off Fantasia at 50," in New York Times , 30 September 1990.

Solomon, Charles, "It Wasn't Always Magic," in Los Angeles Times , 7 October 1990.

Phinney, K., "Shot by Shot," in Premiere (New York), November 1990.

Review, in Listener , vol. 125, no. 3197, 3 January 1991.

Heuring, D., and G. Turner, "Disney's Fantasia: Yesterday and Today," in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), February 1991.

Magid, Ron, "Fantasia-stein," in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), vol. 71, no. 10, October 1991.

Barron, J., "Who Owns the Rights to 'Rites'?" in New York Times , no. 142, 22 January 1993.

Review, in Séquences (Haute-Ville), no. 178, May-June 1995.

Evans, G., "Disney Dishes New Look for Fantasia in 1998," in Variety (New York), no. 358, 6/12 February 1995.

Lyons, M., " Fantasia 2000 ," in Cinefantastique (Forest Park), no. 9, 1998.

* * *

According to Deems Taylor, writing in 1940 (although the story was later denied by Disney sources), Fantasia first began as a comeback vehicle for Mickey Mouse after the Disney Studio had turned from modest cartoon production to large-scale animation features. Certainly Disney had used the Silly Symphony format to introduce additional cartoon figures—Pluto in 1930, the Three Pigs in 1933, and then Donald Duck in 1934, who went on to challenge Mickey's top billing. Also in 1934 Disney began work on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs , a considerable gamble that came to be regarded as "Disney's Folly," but went on to turn a profit of $8 million in its first release in 1937 and earned a special Oscar from the Motion Picture Academy. Pinocchio followed the success of Snow White , introducing Jiminy Cricket as an ingenuous narrator. At this point, then, in 1938, Disney began thinking about a new role for Mickey.

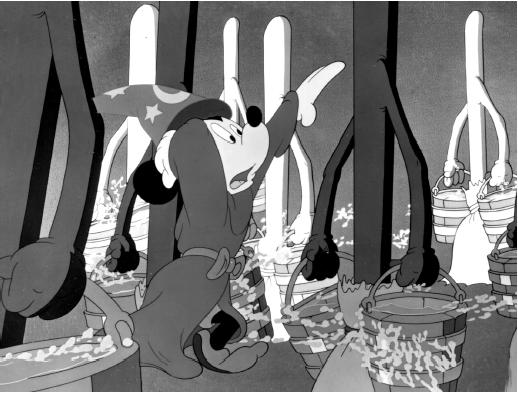

Disney's solution was to make Mickey the lead figure of a special cartoon rendering of "The Sorcerer's Apprentice", a fairy tale that had been set to music by the French composer Paul Dukas. Needing musical advice, Disney broached the project to the conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra, Leopold Stokowski, who was interested not only in the Dukas/Mickey idea but also in extending the project to an animated concert feature. Disney then began thinking in terms of "The Concert Feature" that was to become Fantasia . Whether the idea to expand was Disney's or Stokowski's has also been disputed.

At any rate, Deems Taylor, the radio voice of the Metropolitan Opera, was brought in to provide further advice and to handle the narrative transitions among the concert film's various "movements," involving eight different musical compositions. Disney presumably saw the project as a challenging experiment in animated technique rather than an opportunity to use animation merely as a means of popularizing classical music for the masses. In the Bach Toccata and Fugue portion, for example, Disney artists were encouraged to experiment visually and boldly, in ways never before imagined. This sequence, early in the film, signals its experimentalism, departing from the usual Disney style and moving in abstract directions, imitating the techniques of Oscar Fischinger, who was originally to direct that sequence but left the project before completing it, after discovering the studio had altered his original designs. Other experiments are elsewhere in evidence, as when the sound track is visualized through animation midway through the film, recalling the abstract experiments of Len Lye and anticipating those of Norman McLaren. More conventional Disney whimsy is elsewhere in evidence, however, and there is perhaps the danger of vulgarizing the music through the imposed visual patterns. In fact, the sequences are diverse and uneven.

The film has been criticized for its "ponderous didacticism" (the visualization of the "paleontological cataclysm" in the Stravinsky Rite of Spring sequence, for example, and the simplistic contrasts of the final sequences—Moussorgsky's Night on Bald Mountain against Schubert's Ave Maria , with Good triumphing over Evil in a finale of Christian tranquility) and praised for those sequences in which Disney contented himself with being Disney and avoided self-conscious attempts at being "artistic."

Fantasia came to Disney at a time when risks were being taken. After the demonstrated success of "Disney's Folly," animation began on Fantasia early in 1938. The production cost $2,280,000, including $400,000 for the music alone. Disney began thinking in terms of wide-screen production, multiplane Technicolor, and "Fantasound," representing a major technical innovation involving the use of stereophonic sound and employing a new four-track optical stereophonic system. The achievement of "Fantasound" was something of a compromise: according to Peter Finch, Disney "developed a sound system utilizing seven tracks and thirty speakers," but the system was "prohibitively expensive" and only installed in a few theatres. The score was recorded at the acoustically splendid Academy of Music in Philadelphia.

For the first time, moreover, Disney became his own distributor with Fantasia , since, as Variety reported, the film was so different as to require a different sales approach. It premiered on 13 November 1940, at the Broadway Theatre in New York, and was not an immediate success. Its original running time, with an intermission, was about 130 minutes, later cut to 81 minutes. It was reissued in 1946, but it would only build its audience strength over time. By 1968, for example, it had earned $4.8 million in North American markets, more than doubling its original investment, and finally taking its place among the top 200 grossing films.

In musical terminology, a fantasia is "a free development of a given theme." Disney's achievement, though often impressive and no doubt ahead of its time, has nonetheless had its detractors. Stravinsky was not pleased that his music had been restructured and that the instrumentation had been changed. "I will say nothing about the visual complement," Stravinsky remarked, "as I do not wish to criticize an unresisting imbecility . . . "The film succeeds best when it is at its most playful—the hippopotamus ballerinas in the "Dance of the Hours" sequence, for example, which Richard Schickel has described as "a broad satirical comment on the absurdities of high culture." The visuals for Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony strain contrivedly for a mythic charm in an Arcadian setting populated by fabulous creatures. Far more interesting are the animated dances from Tchaikovsky's Nutcracker Suite, and the whimsical treatment of Ponchielli's "Dance of the Hours" or Mickey's struggle with the dancing brooms in "The Sorcerer's Apprentice," the conceptual core of the picture. John Tibbetts has written that the results of Mickey's "union with high art were questionable for some, just as Walt's collision with the likes of Stravinsky, Beethoven, and Moussorgsky raised (or lowered) many a brow."

Disney's undertaking Fantasia brings to mind an artisan who has only a superficial knowledge of religion undertaking to sculpt a monumental pieta out of sand as the tide moves in, threatening to erode it. Some passers-by will no doubt pause to watch out of curiosity, but the spectacle will not for most of them constitute a conversion. If anything, Fantasia does not teach a musical lesson, but it often fascinates and delights the eye.

Reviewing Fantasia in 1940, Otis Ferguson called it "a film for everybody to see and enjoy," despite its "main weakness—an absence of story, of motion, of interest." Bosley Crowther was less harsh, remarking that the images often tended to overwhelm the music, but praising the film for its "imaginative excursion" and concluding that it was a milestone in motion picture history. Despite its sometimes elaborate pretensions and its many innovations, the boldness of its concept quite overrides the "disturbing jumble" of its achievement. It is, indeed, a "milestone" in the history of animated film.

—James Michael Welsh

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: