Memorias Del Subdesarrollo - Film (Movie) Plot and Review

(Memories of Underdevelopment)

Cuba, 1968

Director: Tomás Gutiérrez Alea

Production: Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematograficos (ICAIC); black and white, 35mm; running time: 104 minutes. Released 1968. Filmed in Havana.

Producer: Miguel Mendoza; screenplay: Tomás Gutiérrez Alea and Edmundo Desnoes, from the novel by Edmundo Desnoes; photography: Ramón Suárez; editor: Nelson Rodríguez; sound engineers: Eugenio Vesa, Germinal Hernández, and Carlos Fernández; production designer: Julio Matilla; music: Leo Brower, conducted by Manuel Duchezne Cuzán, recorded by Medardo Montero; optical effects: Jorge Pucheux; costume designer: Elba Perez; animation: Roberto Riquenes.

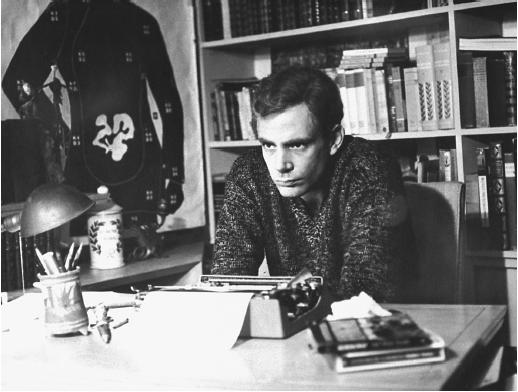

Cast: Sergio Corrieri ( Sergio ); Daisy Granados ( Elena ); Eslinda Núñez ( Noemi ); Omar Valdés; René de la Cruz; Yolanda Farr; Ofelia Gonzáles; José Gil Abad; Daniel Jordan; Luis López; Rafael Sosa.

Awards: Warsaw Festival, Mermaid Prize, 1970.

Publication

Script:

Gutiérrez Alea, Tomás, and Edmundo Desnoes, Memories of Underdevelopment: The Revolutionary Films of Cuba , edited by Michael Myerson, New York, 1973; also contained in Memories of Underdevelopment: Tomas Gutierrez Alea, Director, Inconsolable Memories: Edmundo Desnoes, Author , New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1990.

Books:

Nelson, L., Cuba: The Measure of a Revolution , Minneapolis, 1972.

Chanan, Michael, The Cuban Image , London, 1985.

Burton, Julianne, editor, Cinema and Social Change in Latin America: Conversations with Filmmakers , Austin, 1986.

Sánchez Oliva, Iraida, editor, Viewer's Dialectic: Tomás Gutiérrez Alea , translated by Julia Lesage, Havana, 1988.

Gutiérrez Alea, Tomás, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea: los filmes que no filmé , Ciudad de La Habana, 1989.

Gutiérrez Alea, and Edmundo Desnoes, Memories of Underdevelopment/Inconsolable Memories , introduction by Michael Chanan, New Brunswick, 1990.

Articles:

Douglas, M. E., "The Cuban Cinema: Filmography," in Take One (Montreal), July-August 1968.

Murphy, Brian, in Films and Filming (London), September 1969.

Allen, Don, in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1969.

Engel, Andi, "Solidarity and Violence," in Sight and Sound (London), Autumn 1969.

Bullita, Juan M., in Hablemos de Cine (Lima), no. 54, 1970.

Adler, Renata, "Three Cuban Cultural Reports with Films Some-where in Them," in A Year in the Dark , Berkeley, 1971.

Hamori, O., in Filmkultura (Budapest), January-February 1972.

Murphy, W., in Take One (Montreal), April 1972.

Torres Diaz, D., "Cine Cubano en EEUU," in Cine Cubano (Havana), no. 189–90, 1974.

"The Alea Affair," in Film 73/74 , edited by David Denby and Jay Cocks, Indianapolis, 1974.

Lesage, Julia, "Images of Underdevelopment," in Jump Cut (Chicago), May-June 1974.

Martin, Marcel, in Ecran (Paris), December 1974.

"Three on Two: Henry Fernandez, David I. Grossvogel, and Emir Rodriguez Monegal on Desnoes and Alea," in Diacritics: A Review of Contemporary Cinema , Winter 1974.

Lieberman, S., "Women: The Memories of Underdevelopment ," in Women and Film (Berkeley), Summer 1975.

Burton, Julianne, in Center for Inter-American Relations Review , Fall 1976.

Kernan, Margot, "Cuban Cinema: Tomás Gutiérrez Alea," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Winter 1976.

Burton, Julianne, "Individual Fulfillment and Collective Achievement: An Interview with Tomás Gutiérrez Alea," in Cineaste (New York), January 1977.

Burton, Julianne, in Cineaste (New York), Summer 1977.

Kavanagh, Thomas M., "Dialectics and the Textuality of Class Conflict," and "Revolutionary Cinema and the Self-Reflections on a Disappearing Class" by Albert Michales, in Journal of Latin American Lore , vol. 4, no. 1, 1978.

Fernandez, Enrique, "Witnesses Everywhere: The Rhetorical Strategies of Memories of Underdevelopment ," in Wide Angle (Athens, Ohio), Winter 1980.

Gutiérrez Alea, Tomás, " Memorias del subdesarrollo : Notas de trabajo," and "Se llamaba Sergio" by Edmundo Desnoes, in Cine Cubano (Havana), no. 45–46.

Burton, Julianne, "Modernist Form in Land in Anguish and Memories of Underdevelopment ," in Post Script (Jacksonville, Florida), Winter 1984.

Alexander, W., "Class, Film Language, and Popular Cinema," in Jump Cut (Berkeley), March 1985.

Gutiérrez Alea, Tomás, "The Viewer's Dialectic III," in Jump Cut (Berkeley), no. 32, April 1986.

Lopez, A. M., "Parody, Underdevelopment, and the New Latin American Cinema," in Quarterly Review of Film and Video (New York), no. 1–2, 1990.

Oroz, Silvia, "Mémoires du sous-developpement," an interview with Tomas Gutiérrez Alea, in Revue de la Cinématheque (Montreal), no. 10, February-April 1991.

Thompson, F., "Metaphors of Space: Polarization, Dualism and Third World Cinema," in Screen (Oxford), no. 1, 1993.

"Tomas Gutiérrez Alea: Interview with Cuban Director," in UNESCO Courier , July-August 1995.

Beer, A., "Plotting the Revolution: Identity and Territory in Memories of Underdevelopment ," in CineAction (Toronto), no. 43, 1997.

* * *

The self and society, private life and history, individual psychology and historical situation—this is the core of Memories , and film has rarely (if ever) been used so effectively to portray this relationship. The dialectic of consciousness and context is presented through the character of Sergio, a wealthy but alienated member of the bourgeoisie who stays in Cuba after the triumph of the revolution and whose experiences, feelings, and thoughts in being confronted by the new reality form the basis of the film.

The formal inventiveness of the film has its origin in the dialectical resonance created through the juxtaposition of various cinematic forms, a characteristic of revolutionary Cuban cinema at its best. Here, the film begins by re-working the book which inspired it, taking the form of the novel—Sergio's subjective revolutionary Cuba, presented in documentary footage. Through this formal juxtaposition, the film "objectifies" the internal monologue of Sergio—criticizing and contextualizing his psychological subjectivism and confronting his attempts to retreat into his pre-revolutionary psychology and ways of seeing with the "fact of history" presented by the revolutionary situation.

Visually, the film's dialectic is presented through the use of three forms of cinematic structure. Documentary and semi-documentary footage is used to depict the "collective consciousness" of the revolutionary process, a consciousness that is pre-eminently historical. This footage presents us with the background of the revolution and establishes the historical context of the film's fictional present by placing it between the 1961 exodus in the aftermath of the failed Bay of Pigs invasion and the defensive preparations for the Missile Crisis of 1962. Fictional footage is used in two ways. The majority of the fictional sequences are presented in the traditional form of narrative cinema, in which the camera functions as omniscient narrator. However, at times the camera presents us with Sergio's point-of-view, the way in which his consciousness realizes itself in his forms of perception—what he looks at and how he sees it. Thus, the film shows and creates an identification with what it is simultaneously criticizing. Through this juxtaposition of visual forms, and through the visual contradiction of Sergio's reflections, the film insists that what we see is a function of how we believe, and that how we believe is what our history has made of us.

Sergio's way of seeing was formed in pre-revolutionary Cuba. As a member of the educated elite, he developed a disdain for Cuban reality and a scorn for those who believe that it could be changed. Critical of his bourgeois family and friends (who are, however, capable of making the commitment to leave Cuba), he is nonetheless unable to overcome his alienation and link himself to the revolution. The "ultimate outsider," he attempts to content himself by colonizing and exploiting women—a metaphor for the colonization of Cuba. His personal fate is finally and paradoxically irrelevant, for as the film ends the camera moves out from his individual vision to the larger revolution beyond.

The film "shocked" U.S. critics when released there in 1973, and they described it variously as "extremely rich," "hugely effective," "beautifully understated," and "a miracle." No "miracle" at all, but simply one of the finest examples of revolutionary Cuban cinema, Memories has also received a warm reception from Cuban audiences, some film-goers returning to see it again and again. Memories ' complex structure and dialectical texture merit such repeated viewings, for it transforms the now familiar themes of alienation and the "outsider" by placing them within a revolutionary setting. We identify with and understand Sergio, who is capable of moments of lucidity. However, we also understand that his perspective is neither universal nor timeless but a specific response to a particular situation. Memories of Underdevelopment insists that such situations are not permanent and that things can be changed through commitment and struggle. History is a concrete, material process which, ironically, is the salvation of the Sergios.

—John Mraz

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: