The Matrix - Film (Movie) Plot and Review

USA, 1999

Directors: Andy Wachowski and Larry Wachowski

Production: Village Roadshow Productions, Grouch II Film Partnership, and Silver Pictures; distributed by Warner Brothers; color, 35mm; running time: 136 minutes; sound mix: DTS, Dolby Digital, SDDS. Released March 1999, USA. Filmed in Sydney, Moore Park, and Waterloo, Australia, and in Istanbul, Turkey; cost: $63 million.

Producers: Bruce Berman (executive), Dan Cracchiolo (co-producer), Carol Hughes (associate), Andrew Mason (executive), Richard Mirisch (associate), Barrie Osborne (executive), Joel Silver, Erwin Stoff (executive), Andy Wachowski (executive), Larry Wachowski (executive); screenplay: Andy Wachowski, Larry Wachowski; cinematography: Bill Pope; assistant directors: Colin Fletcher, Bruce Hunt, James McTeigue, Toby Pease, Tom Read, Noni Roy, Jeremy Sedley, Paul Sullivan; editor: Zach Staenberg; supervising sound editor: Dane Davis; art directors: Hugh Bateup, Michelle McGahey; production designer: Owen Paterson; costume designer: Kym Barrett; original music: Don Davis; sound effects editors: Julia Evershade, David Grimaldi, Eric Lindemann; casting: Mali Finn, Shauna Wolifson; special effects supervisors: Steve Courtley, Brian Cox; visual effects supervisors: Lynne Cartwright (Animal Logic), John Gaeta; digital effects supervisor: Rodney Iwashina; Bullettime composite supervisor: John Sasaki; stunt coordinator: Glenn Boswell; set designer: Godric Cole; music supervisor: Jason Bentley; kung fu choreographer: Yuen Wo Ping.

Cast: Keanu Reeves ( Thomas A. Anderson/Neo ); Laurence Fishburne ( Morpheus ); Carrie-Anne Moss ( Trinity ); Hugo Weaving ( Agent Smith ); Gloria Foster ( Oracle ); Joe Pantoliano ( Cypher/Mr. Reagan ); Marcus Chong ( Tank ); Julian Arahanga ( Apoc ); Matt Doran ( Mouse ); Belinda McClory ( Switch ); Ray Anthony Parker ( Dozer ); Paul Goddard ( Agent Brown ); Robert Taylor ( Agent Jones ); David Aston ( Rhineheart ); Marc Gray ( Choi ); Ada Nicodemou ( DuJour ); Denni Gordon ( Priestess ); Rowan Witt ( Spoon Boy ); Fiona Johnson ( Woman in Red ); Andy Wachowski ( Window cleaner , uncredited); Larry Wachowski ( Window cleaner , uncredited).

Awards: Academy Awards for Best Editing (Zach Staenberg), Best Effects, Sound Effects Editing (Dane A. Davis), Best Effects, Visual Effects (Steve Courtley, John Gaeta, Janek Sirrs, Jon Thum), and Best Sound (David E. Campbell, David Lee, John T. Reitz, Gregg Rudloff), 2000; Academy of Science Fiction, Horror, and Fantasy Films Awards for Best Science Fiction Film, Best Director (Andy and Larry Wachowski), Best Actor (Keanu Reeves), Best Costume Design

Publications

Script:

Wachowski, Andy, Larry Wachowski, Geof Darrow, Phil Osterhouse, Steve Skroce, and Spencer Lamm (editor), The Matrix: The Shooting Script and Complete Storyboards , New York, 2000.

Articles:

Palermo, Chandra, "Ghost in the Machine," in Cinescape , vol. 5, no. 2, March 1999.

McCarthy, Todd, "Silly F/X, Matrix Are For Kids," in Variety , vol. 374, no. 6, 29 March 1999.

Schwarzbaum, Lisa, "Techno Prisoners," in Entertainment Weekly , no. 480, 9 April 1999.

Essex, Andrew, "Matrix Mania," in Entertainment Weekly , no. 485, 14 May 1999.

Graham, Bob, "Reeves Lost in The Matrix /Skillful Effects Serve Pretentious Sci-Fi Yarn," in The San Francisco Chronicle , 24 September 1999.

Wright, Richard, "The Matrix Rules," in Film-Philosophy Internet Salon , http://www.film-philosophy.com , vol. 5, no. 3, January 2000.

Hutchings, Peter, "The Matrix," in Scope: An Online Journal of Film Studies , http://www. nottingham.ac.uk/film/journal/filmrev/the_matrix.htm , May 2000.

* * *

Three years after impressing critics with their Hollywood debut, Bound —a visually-stunning, highly suspenseful, lesbian neo-noir— Chicago-based brothers Andy and Larry Wachowski conceived of, wrote, and directed The Matrix , a science-fiction blockbuster that managed to effectively fuse (a là Star Wars ) pop-philosophical themes with skillfully choreographed action sequences and state-ofthe-art special effects.

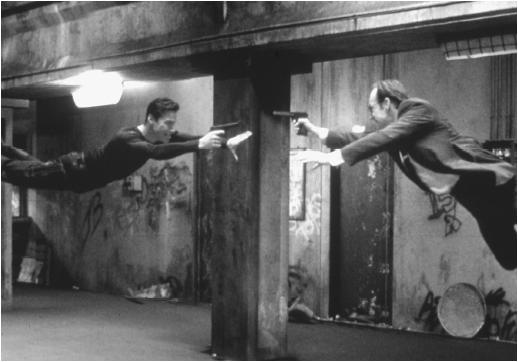

The film stars Keanu Reeves (in a role that may have resuscitated his flagging career) as a dutiful company man who doubles at night as a hacker named Neo. Neo's Cartesian-esque scepticism concerning the true nature of reality is validated after a beautiful mystery woman, Trinity (Moss), introduces him to legendary zen-hacker Morpheus (Fishburne). Accepting Morpheus's invitation to take a mind/brain opening techno-drug trip, Neo discovers that the world in which he previously "existed" is nothing but a computer-generated Virtual Reality program controlled by the very artificial intelligence machines developed by mankind years ago. It seems that the machines, which require endless supplies of electrical current to survive, keep the entire human population (save for a smattering of rebels and one underground city) in a state of perpetual hallucination; lying unconscious in automated incubators, people are deceived into believing that they are actually living productive lives, while in reality vampiric computers are siphoning off their precious mojo. Morpheus is certain that Neo is the Messianic "One" who, according to legend, will show up one day to save the human race from eternal subjugation. Although initially dissuaded by a surprisingly domestic soothsayer (Foster), Neo manages to summon the inner fortitude necessary to defeat the waspy A.I. defense squad with the help of John Wooian martial arts-ballet, Sam Peckinpah-inspired slow motion gunfighting, and repeated self-affirmations.

The Matrix stands as the most successful entry in the budding scifi subgenre of Virtual Reality pictures. Other entries include John Carpenter's They Live! (1988), Paul Verhoeeven's Total Recall (1990), Brett Leonard's Lawnmower Man (1992), Katheryn Bigalow's Strange Days (1995), Alex Proyas's Dark City (1998), Josef Rysnak's The Thirteenth Floor (1999), and David Cronenberg's eXistenZ (1999). Metaphysical musings, justified paranoia, and a constant questioning of authority are staples of all these films, which find nottoo-distant relatives in Peter Weir's The Truman Show (1998) and Gary Ross's Pleasantville (1998). Separating The Matrix from the rest of the pack are its epic pretensions, apocalyptic overtones, and breathtaking visuals. New technologies such as "Bullettime" super slo-mo photography, wire enhanced gymnastics, and Woo-Ping Yuen ( Black Mask , Fist of Legend )-choreographed Kung Fu fight scenes together served to raise the bar significantly for big-budget Hollywood action sequences. At the time of its release, producer Joel Silver gushed that "The style and the visual effects within [ The Matrix ] are something that has never been seen before, plus we have fighting styles and photographic techniques used in this movie that weren't possible even six months ago." Some of the fight scenes were so distinctive that spoofs turned up in the Rob Schneider vehicle, Deuce Bigalo: Male Gigolo (1999), as well as in one of the popular 1–800-CALL-ATT commercials starring David Arquette. Perhaps Peter Hutchings summed it up best when he wrote that The Matrix "replace[s] what in Woo is possible if unlikely with what is completely impossible."

The romanticized, even glorified depiction of violence in The Matrix came under attack after a pair of teenage boys, dressed in black trenchcoats not unlike the one worn by Neo, went on a shooting spree at their high school in Littleton, Colorado, a mere sixteen days after the film opened. Twelve students and one teacher were left dead; dozens more were seriously injured. Distraught parents and outraged politicians cited The Matrix 's numerous fight scenes—scenes in which the heroes possess a seemingly inexhausible supply of guns and ammo, move with acrobatic grace, and suffer little if any pain or negative consequences—as stimulants to the real-life massacre. (It is worth noting that the Wachowski brothers are former comic book writers, a pop literary genre in which scenes such as these are ubiquitous.) Although debate over the possible effects of cinematic violence on impressionable adolescents has raged for decades, the Littleton shootings brought the issue to the fore, and Hollywood had no choice but to respond with vague public statements and the temporary shelving of some controversial projects (the title of Kevin Williamson's Killing Ms. Tingle , about a nasty high school teacher who gets imprisoned by a few of her students, was changed just before its release to the far less indelicate, far less interesting, Teaching Ms. Tingle ).

One of the most fascinating things about The Matrix is the manner in which the film attempts to negotiate, with only moderate success, between progressive messages of non-conformity and self-realization, and the generic imperatives imposed by Hollywood's conservative studio system. Roger Ebert put the point succintly when he wrote that "It's cruel, really, to put tantalizing ideas on the table and then ask the audience to be satisfied with a shoot-out and a martial arts duel." Other critics praised the Wachowski brothers for beginning their film with an extended fight scene starring Trinity, only to note with disappointment her relegation to "Neo's love interest" status for the rest of the picture. The Matrix 's mixed messages reappear at the level of narrative. Considering that what remains of post-war planet Earth is a bleak, inhospitable "desert of the real," and that the virtual world in which Neo grew up is not without its advantages, it is not entirely clear what the human resistance hopes to gain by its struggles.

In the final analysis, The Matrix stands as a textbook example of what has been called "postmodern" art, in which allusions to other texts (cinematic and otherwise) dominate, and nothing is referred to besides other representations. From the Bible to The Wizard of Oz , from Sleeping Beauty to Alice in Wonderland , from The Wild Bunch to Hard Target , The Matrix quotes from a multitude of sources, and in so doing adds an ironic twist to a film that is ostensibly concerned with exposing the limitations of simulated modes of experience.

—Steven Schneider

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: