The Misfits - Film (Movie) Plot and Review

USA, 1961

Director: John Huston

Production: Seven Arts Productions; black and white, 35mm and 16mm; running time: 125 minutes.

Producer: Frank E. Taylor; screenplay: Arthur Miller; photography: Russell Metty; editor: George Tomasini; assistant director: Carl Beringer; art directors: Stephen Grimes, Bill Newberry; music: Alex North; sound recording: Phil Mitchell.

Cast:

Clark Gable (

Gay Langland

); Marilyn Monroe (

Roslyn Taber

); Montgomery Clift (

Perce Howland

); Eli Wallach (

Guido

); Thelma Ritter (

Isabelle Steers

); Kevin McCarthy (

Raymond Taber

).

Publications

Script:

Garret, G.P., and others, Film Scripts 3 , New York, 1972.

Books:

Kaminsky, Stuart, John Huston: Maker of Magic , London, 1978.

Madsen, Axel, John Huston , New York, 1978.

Goode, James, The Making of The Misfits , Indianapolis, 1986.

McCarthy, John, The Films of John Huston , Secaucus, New Jersey, 1987.

Studlar, Gaylyn, editor, and David Desser, Reflections in a Male Eye: John Huston & the American Experience , Washington, D.C., 1993.

Cooper, Stephen, editor, Perspectives on John Huston , New York, 1994.

Brill, Lesley, John Huston's Filmmaking , New York, 1997.

Cohen, Allen, John Huston: A Guide to References and Resources , London, 1997.

Articles:

Variety (New York), 1 February 1961.

Cieutat, M., Positif (Paris), October 1961.

Oms, Marcel, Positif (Paris), September 1961.

Hart, Henry, Films in Review (New York), February 1961.

Lejeune, C.A, Films and Filming (London), June 1961.

Monthly Film Bulletin (London), July 1961.

Cieutat, Michel, " Les Misfits ," in Positif (Paris), no. 260, October 1982.

Listener , vol. 116, no. 2967, 3 July 1986.

"Miller + Huston = Les Misfits ," in Cinéma (Paris), no. 422, 30 December 1987.

Lippe, R., "Montgomery Clift: A Critical Disturbance," in CineAction (Toronto), no. 17, Summer 1989.

Miller, A., "Snips About Movies," in Michigan Quarterly Review , vol. 34, no. 4, 1995.

Shoilevska, Sanya, "Alex North's Score for The Misfits ," in Cue Sheet (Hollywood), vol. 7, no. 2, April 1996.

Jacobowitz, F., and R. Lippe, "Performance and the Still Photograph: Marilyn Monroe," in CineAction (Toronto), no. 44, 1997.

* * *

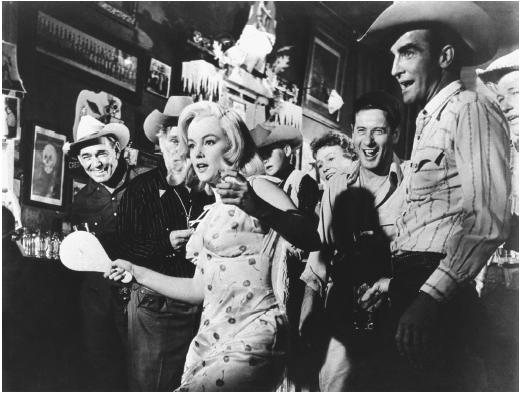

Some thirty years after its release, The Misfits remains an impressive and affecting film but nonetheless a failure. The film, which is based on a screenplay written by Arthur Miller expressly as a homage to his wife, Marilyn Monroe, shies away from probing too deeply into its material and never manages to integrate its various thematics into an organic whole. Monroe's character, Roslyn, is the centre of the film and the character's impact on the men she meets gives the film its structure and narrative movement. In regard to Monroe/Roslyn, the film is highly reflexive and cannot but be read in part as a meditation on Monroe's star image, persona and presence.

The first time Monroe appears on-screen, she is attempting unsuccessfully to memorize the lines she needs to say in a divorce court hearing; as she rehearses, her face is seen reflected in a mirror as she puts finishing touches on her made-up face. To anyone even slightly familiar with Monroe's star image, the introductory sequence signals that the film is to be read as being about Marilyn Monroe. As the film progresses, there are other references to Monroe's public persona—like the actress, Roslyn was abandoned early on by her parents and grew up searching for love and security. Of the various references to Monroe, the strongest and most significant is the character's femininity and her almost exquisite sensitivity to human experience. Monroe/Roslyn is presented as an essence of the "feminine." The image is in keeping with the direction Monroe's screen persona and presence was taking in the late 1950s—she was no longer the dumb blonde but the innocent; whereas earlier in her career, she embodied physicality, she now is presented as representing the spirit of a life-force. The film underscores this conception of Monroe/Roslyn by having each of the principal male characters comment on her ability to feel, to intuitively respond to and empathize with human life and nature. The Misfits was Monroe's first dramatic film as a major star and was intended to consolidate her image as a serious person (New York and the Actor's Studio, a film with Olivier, the marriage to Arthur Miller) and actor.

With so much emphasis placed on Monroe and her femininity, it is highly fitting that her co-star in The Misfits is Clark Gable. Gable's star persona had been built on his masculine appeal. If Monroe was the 1950s archetypal female, Gable was the traditional archetypal male. As iconic figures the pairing of the two has a certain logic although their respective screen personas do not particularly mesh. While The Misfits is about Monroe, it is equally a meditation on both heterosexual relations and the conflict between the feminine and the masculine. As conceived by Miller and the film's director, John Huston, the feminine and the masculine are taken on face value. There is no consideration that an individual person may embody feminine and masculine traits or that the concepts themselves are cultural constructions. Montgomery Clift's presence and his characterization are the closest the film comes to acknowledging the possibility of a person having both a feminine and masculine identity but the character he plays is intended to be contrasted to Gable and Eli Wallach, a friend of Gable's who is gradually revealed to be irredeemably embittered, cynical and a misogynist; Gable and Wallach are "men" and not the man-child Clift is presented as being.

In The Misfits a masculine presence is interchangeable with a male's heterosexual orientation and Gable's "manly" image is further enhanced in that he is a cowboy. It is Gable's mature (that is, aging) cowboy which is used by the film to both place the Monroe character and provide a lament for the passing of a "genuine" masculine ethos which has been eroded by urbanization, women, and the death of the West and the male world of freedom, action, and mastery. In regard to Monroe and Gable's relationship, the film has two primary concerns: although Monroe is extremely attuned to other people's feelings and needs, she doesn't fully comprehend until late in the narrative that Gable is in emotional pain; and, secondly, as the mustang hunt dramatizes, while Gable is willing to acknowledge that he and the West belong to a bygone era, he needs to maintain his self-respect and not be "broken" ie emasculated. The Misfits moves to a climactic confrontation between Monroe and Gable over his sensitivity and hurt and it is Monroe who must give way if their relationship is to have a future.

The Misfits somewhat uneasily places its struggle between the female and male within the context of the crisis of the nuclear family; Roslyn had experienced an unhappy childhood, Gable's Gay has had an unsuccessful marriage and he and his children have a strained relationship, and Clift's Perce feels alienated from his mother who has chosen a second husband/lover over his affections. In the film's "happy ending" resolution, Monroe and Gable drive off together with her letting him know that she is now ready to have a child.

If the film's "troubled-family" thematic points back to the 1950s, The Misfits also looks forward to the 1960s and beyond. In addition to its self-conscious presentation of Monroe and, for that matter, Gable and Clift, the film is an early 1960s attempt to critically address the Western, the genre's values and its contemporary status. It is also a (post)modern film in the privileging of digression and ambience over narrative. And, in embryonic form, Monroe's identity raises issues directly relevant to feminism; she also aligns herself to what are essentially environmental and animal rights issues.

Although the film lacks a strong narrative drive, Huston's direction is taut and Russell Metty's elegantly sombre and sparse black and white images provide the feel of a spontaneous and almost documentary-like approach to the material. The Misfits lends itself to readings from numerous critical perspectives but it is perhaps most meaningfully a film concerned with stardom and in particular its complex relation to both the star and her or his audience. As the film illustrates, Monroe hadn't really resolved the split between her being perceived as a sex symbol (the paddle-ball sequence) and as a serious performer. And, the fact that The Misfits is Monroe's and Gable's final film and one of Clift's last efforts, makes it an inescapably sad film.

—Richard Lippe

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: