La Primera Carga Al Machete - Film (Movie) Plot and Review

(The First Charge of the Machete)

Cuba, 1969

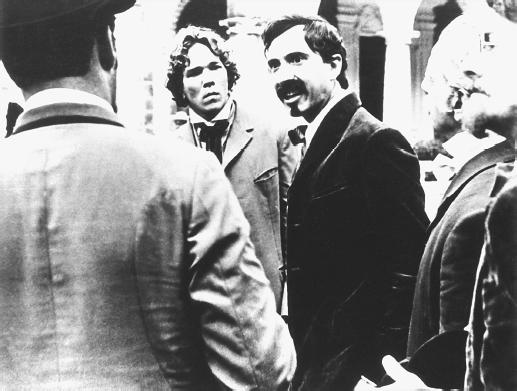

Director: Manuel Octavio Gómez

Production: Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC); black and white, 35mm, Panoramic; running time: 84 minutes. Released 1969. Filmed in Cuba.

Screenplay: Manuel Octavio Gómez, Alfredo L. Del Cueto, Jorge Herrera, and Julio García Espinosa; editor: Nelson Rodríguez; sound: Raúl Garcia; music: Leo Brouwer; songs: Pablo Milanés; costume designer: Maria Elena Molinet.

Cast:

Adolfo Llauradó; Idalia Anreus; Eslinda Nuñez; Ana

Viñas.

Publications

Books:

Nelson, L., Cuba: The Measure of a Revolution , Minneapolis, 1972.

Chanan, Michael, The Cuban Image , London, 1985.

Burton, Julianne, editor, Cinema and Social Change in Latin America: Conversation with Filmmakers , Austin, Texas, 1986.

Articles:

Hablemos de Cine (Lima), no. 54, 1970.

Mikko, Pyhala, "Cuba," in International Film Guide , London, 1971.

Díaz Torres, Daniel, in Cine y revolución en Cuba , edited by Santiago Alvarez and others, Barcelona, 1975.

Burton, Julianne, "Popular Culture and Perpetual Quest: An Interview with Manuel Octavio Gómez," in Jump Cut (Berkeley), May 1979.

Colina, Enrique I., in Cine Cubano (Havana), nos. 56–57.

Lopez Morales, E., " La primera cargap A la luz del tiempo," in Cine Cubano (Habana), no. 122, 1988.

Quiros, O., "Critical Mass of Cuban Cinema: Art as the Vanguard of Society," in Screen (Oxford), vol. 37, no. 3, 1996.

* * *

Even within the context of revolutionary Cuban cinema—distinguished for its innovations in bringing history to the screen— First Charge is a whole new kind of historical film. Produced as a part of a cycle dedicated to the celebration of "One Hundred Years of Struggle," the film fuses the political and the poetic into a reconstruction of the 1868 uprising against Spanish colonials and in so doing redefines historical cinema.

The experimental nature of First Charge is immediately apparent in the richness of its formal structure. The film is designed to appear as if the technological capabilities (and resulting aesthetic) of cinema verité had been available in 1868. Light hand-held cameras and portable sound equipment produce "on-the-spot" interviews and follow the Cuban rebels into the very center of the battle. This eminently modern "TV documentary" style is complimented, however, by a high-contrast film that resembles ancient newsreel footage and by a manner of posing individuals at the beginning of sequences as if they were in old historical photos. The clash of aesthetics at once so up-to-the-minute and so archaic results in the formal "dialectical resonance" for which Cuban cinema has attained such renown.

This formal juxtaposition, and the various techniques contained within it, has a meaning beyond mere experimentation for its own sake. Manuel Octavio Gómez uses this confrontation of past and present to insistently remind viewers that they are seeing an interpretation of the historical event, not the event itself. The high-contrast film also functions metaphorically, for it connotes the extremes of the struggle and the reality of sharply opposed interests, in which compromise was impossible. The use of contrast is set up against the grey tones employed in the official pronouncements of the Spanish, which are intended to convey a false impression of tranquility. The hand-held camera and the provocative interviewing style also have connotative functions, for they take on the form of participating in and helping to precipitate the struggle. Gómez's rejection of the narrative structure traditional in historical cinema is important as well, for, in place of characters with whom one identifies, the film's central protagonist is the machete—the work tool which became a weapon in 1868 and the weapon of 1868 which is today the tool of Cuba's economic struggle.

Gómez combined extensive historical research with his use of such deliberately anachronistic devices. Cuban and Spanish archives were mined for materials dealing with the struggle, and historical photographs, etchings, and documentary footage were studied in depth. The film's dialogues are constructed entirely from documents, books, speeches, reports, letters, and anecdotes from the period, and, although it was not possible to reconstruct the language patterns of 1868, the actors were required to immerse themselves in this historical material.

Audiences inside and outside of Cuba responded favorably to the film, although some people were put off by the exaggerated expressionism of the visual style. At times—most notably in the final battle—the combination of extreme high-contrast film and the widely careening hand-held camera of Jorge Herrera reduce the screen image to a swirling mass of abstract patterns. One critic saw the technique as "obsessive and vampire-like" in detracting from the story-line; Gómez himself acknowledged that the "brusque and violent" camera movements "molest" viewers. However, Gómez defends his film's style as part of the struggle against the "routinization" of audience and filmmaker. If First Charge does not quite attain the goals set for it by Gómez, that is because he has aimed so high.

—John Mraz

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: