Salvatore Giuliano - Film (Movie) Plot and Review

Italy, 1961

Director: Francesco Rosi

Production: Lux Film and Vides-Galatea (Italy); black and white, 35mm; running time: 125 minutes, some sources list 135 minutes. Released 1961. Filmed in Sicily.

Producer: Franco Cristaldi; screenplay: Francesco Rosi, Suso Cecchi D'Amico, Enzo Provenzale, and Franco Solinas, based on official court records and journalistic reports on the career of Salvatore Giuliano; photography: Gianni Di Venanzo; editor: Mario Serandrei; sound: Claudio Maielli; art directors: Sergio Canevari and Carlo Egidi; music: Piero Piccioni; costume designer: Marilù Carteny.

Cast: Frank Wolff ( Gaspare Pisciotta ); Salvo Randone ( President of Viterbo Assize Court ); Federico Zard ( Pisciotta's defense counsel ); Pietro Camarata ( Salvatore Giuliano ); Fernando Cicero ( Bandit ); Sennuccio Benelli ( Reporter ); Bruno Ekmar ( Spy ); Max Cartier ( Francesco ); Giuseppe Calandra ( Minor official ); Cosimo Torino ( Frank Mannino ); Giuseppe Teti ( Priest of Montelepre ); Ugo Torrente.

Awards:

Berlin Film Festival, Best Direction, 1962.

Publications

Books:

Rondi, Gian Luigi, The Italian Cinema Today 1952–1965 , New York, 1966.

Wlaschin, Ken, Italian Cinema Since the War , Cranbury, New Jersey, 1971.

Bolzoni, Francesco, I film di Francesco Rosi , Rome, 1986.

Ciment, Michel, Le Dossier Rosi: Cinéma et politique , Paris, 1976; revised edition, 1987.

Kezich, Tullio, Salvatore Giuliano , Acicatena, Italy, 1991.

Testa, Carlo, editor, Poet of Civic Courage: The Films of Francesco Rosi , Westport, 1996.

Articles:

Films and Filming (London), December 1962.

Bean, Robin, in Films and Filming (London), June 1963.

Lane, John, in Films and Filming (London), August 1963.

"Francesco Rosi: Interview," in Film (London), Spring 1964.

Thomas, John, in Film Society Review (New York), September 1966.

Ravage, Maria-Teresa, in Film Society Review (New York), October 1971.

Crowdus, Gary, and D. Georgakas, "The Audience Should Not Be Just Passive Spectators," in Cinearte (New York), no. 1, 1975.

Netzeband, G., "Eisenstein, Rosi, Kieslowski und andere," in Film und Fernsehen (Berlin), no. 12, 1979.

Baker, F. D., "Solo lo psicologo del film e non del personaggio: Colloquio con Francesco Rosi," in Cinema Nuovo (Turin), October 1979.

"Rosi Issue" of Cinema (Zurich), vol. 28, no. 2, 1982.

Elbert, L., in Cinemateca Revista (Montevideo), November 1983.

Domecq, J.-P., in Positif (Paris), April 1984.

Ciment, Michel, "Rosi in a New Key," in American Film , vol. 9, September 1984.

Rosi, Francesco, in Filmkultura (Budapest), January 1986.

Dibilio, P., "Quand Rosi filmait Giuliano," in Cinéma (Paris), no. 424, 13 January 1988.

"Spéciale première," in Revue du Cinéma (Paris), no. 435, February 1988.

Crowdus, G., "Francesco Rosi: Italy's Postmodern Neorealist," in Cineaste (New York), vol. 20, no. 4, 1994.

Klawans, Stuart, and Howard Feinstein, "Illustrious Rosi," in Film Comment (New York), vol. 31, no. 1, January-February 1995.

Restivo, Angelo, "The Economic Miracle and Its Discontents: Bandit Films in Spain and Italy," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), vol. 49, no. 2, Winter 1995–1996.

"La Sicilia al presente storico: Salvatore Giuliano ," in Castoro Cinema (Milan), no. 31/32, 2nd edition, March 1998.

* * *

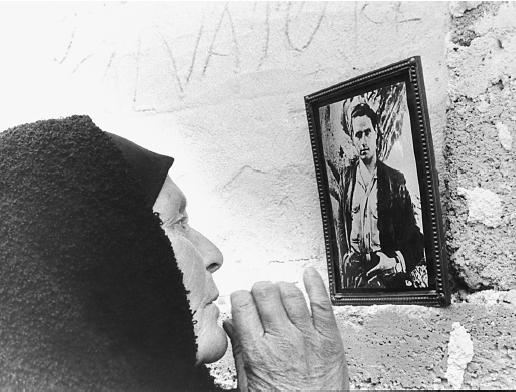

Salvatore Giuliano, a Sicilian bandit who became a force in that island's violent political affairs from the end of World War II until his violent death in 1950, is the subject of the third feature film by Francesco Rosi, former assistant director to Luchino Visconti. But in a real sense it is Sicily—the texture of its land and the interwoven social and political forces which shaped the career of this bandit—that is the true subject of the film.

In many ways Salvatore Giuliano produces the effect of documentary. The scenario is based on extensive research into official court records as well as historical and journalistic reports surrounding the

The non-fictional subject is the basis of a complex structure which relies more on selection of events and reconstruction than on invention. The major structuring device is a voice-over narration, spoken by Rosi himself in the Italian version. This device, along with a few printed titles, accounts for much of the film's documentary impact and serves to specify space and time in the major narrative sections.

The structure alternates events following the bandit's death in 1950 with flashbacks chronicling his career from the end of World War II. Within both the present and the flashback segments, the development is chronological but sharply elliptical. Within the flashbacks, events are selected around certain themes in Sicilian politics and Giuliano's career—the Separatist movement, kidnapping, the attack on a leftist peasant gathering.

The voice-over, with its verbal overload of information may contribute as much as the temporal structure to the film's ambiguity. The various sources of power in Sicily—government, Separatists, police, army—are all eventually linked with the mafia, a connection more often implied by juxtaposition of image and voice-over than by direct statement.

Salvatore Giuliano is concerned with Sicily not only in terms of its politics. The film was shot on location, using Sicilian non-professionals as actors. Sweeping camera movements describe the uneven terrain that concealed and protected the bandits from their opponents.

Rosi systematically withholds critical information. The bandit himself is on view as a corpse in the first sequence and then appears briefly several times in the flashbacks, his identity often obscured. And yet Rosi took pains to select an actor who resembled the real bandit. Giuliano's murderer is the closest approximation to a developed character, although he emerges from the background very late in the film.

The lack of emphasis on characters is one clear distinction between this 1961 film and Italian neorealism. There is also, despite the location shooting and the careful research that contributed to the film, a new scepticism regarding the status of photographic reality. In the opening scene, a city official reads a fastidiously detailed description of the death scene, its precision revealing absolutely nothing. In the course of the film, the viewer is shown that these apparent circumstances mask a complicated system of deception.

—Ann Harris

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: