Det Sjunde Inseglet - Film (Movie) Plot and Review

(The Seventh Seal)

Sweden, 1957

Director: Ingmar Bergman

Production: Svensk Filmindustri; black and white, 35mm; running time: 96 minutes. Released 16 February 1957, Stockholm. Filmed in

Producer: Allan Ekelund; screenplay: Ingmar Bergman, from his dramatic sketch Wood Painting ; photography: Gunnar Fischer; editor: Lennart Wallin; sound: Aaby Wedin and Lennart Wallin; special sound effects: Evald Andersson; sets: P. A. Lundgren; music: Erik Nordgren; costume designer: Manne Lindholm.

Cast: Bengt Ekerot ( Death ); Nils Poppe ( Joff ); Max von Sydow ( The Knight, Antonius Blok ); Bibi Andersson ( Mia ); Inga Gill ( Lisa ); Maud Hansson ( Tyan, the witch ); Inga Landgré ( Knight's wife ); Gunnal Lindblom ( The girl ); Berto Anderberg ( Raval ); Anders Ek ( Monk ); Ake Fridell ( Plog, the smith ); Gunnar Olsson ( Church painter ); Erik Strandmark ( Skat ); Benkt-Åke Benktsson ( The merchant ); Gudrum Brost ( Woman at the inn ); Ulf Johansson ( Leader of the soldiers ); Lars Lind ( The young monk ); Gunnar Börnstrand ( Jöns, the squire ).

Awards: Cannes Film Festival, Special Prize, 1957.

Publications

Script:

Bergman, Ingmar, The Seventh Seal , in Four Screenplays of Ingmar Bergman , New York, 1960; also published separately, London and New York, 1963.

Books:

Béranger, Jean, Ingmar Bergman et ses films , Paris, 1959.

Höök, Marianne, Ingmar Bergman , Stockholm, 1962.

Chiaretti, Tommaso, Ingmar Bergman , Rome, 1964.

Donner, Jörn, The Personal Vision of Ingmar Bergman , Bloomington, Indiana, 1964.

Nelson, David, Ingmar Bergman: The Search for God , Boston, 1964.

Steene, Birgitta, Ingmar Bergman , New York, 1968.

Gibson, Arthur, The Silence of God: Creative Response to the Films of Ingmar Bergman , New York, 1969.

Wood, Robin, Ingmar Bergman , New York, 1969.

Sjögren, Henrik, Regi: Ingmar Bergman , Stockholm, 1970.

Young, Vernon, Cinema Borealis: Ingmar Bergman and the Swedish Ethos , New York, 1971.

Steene, Birgitta, Focus on the Seventh Seal , Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1972.

Björkman, Stig, and others, editors, Bergman on Bergman , New York, 1973.

Ranieri, Tino, Ingmar Bergman , Florence, 1974.

Kaminsky, Stuart, editor, Ingmar Bergman: Essays in Criticism , New York, 1975.

Bergom-Larsson, Maria, Ingmar Bergman and Society , San Diego, 1978.

Kawin, Bruce, Mindscreen: Bergman, Godard, and the First-Person Film , Princeton, 1978.

Marion, Denis, Ingmar Bergman , Paris, 1979.

Manvell, Roger, Ingmar Bergman: An Appreciation , New York, 1980.

Mosley, Philip, Ingmar Bergman: The Cinema as Mistress , Boston, 1981.

Petric, Vlada, editor, Film and Dreams: An Approach to Bergman , South Salem, New York, 1981.

Cowie, Peter, Ingmar Bergman: A Critical Biography , New York, 1982.

Livingston, Paisley, Ingmar Bergman and the Ritual of Art , Ithaca, New York, 1982.

Steene, Birgitta, Ingmar Bergman: A Guide to References and Resources , Boston, 1982.

Jones, William G., editor, Talking with Bergman , Dallas, 1983.

Lefèvre, Raymond, Ingmar Bergman , Paris, 1983.

Slayton, Ralph Emil, Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal: A Criticism , Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1983.

Dervin, Daniel, Through a Freudian Lens Deeply: A Psychoanalysis of Cinema , Hillsdale, New Jersey, 1985.

Gado, Frank, The Passion of Ingmar Bergman , Durham, North Carolina, 1986.

Bergman, Ingmar, Laterna Magica , Stockholm, 1987; as The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography , London, 1988.

Cohen, James, Through a Lens Darkly , New York, 1991.

Bjorkman, Stig, Torsten Maans, and Jonas Sima, Bergman on Bergman: Interviews with Ingmar Bergman , Cambridge, 1993.

Cohen, Hubert I., Ingmar Bergman: The Art of Confession , New York, 1993.

Long, Robert Emmet, Ingmar Bergman: Film & Stage , New York, 1994.

Tornqvist, Egil, Between Stage and Screen: Ingmar Bergman Directs , Amsterdam, 1995.

Blackwell, Marilyn J., Gender and Representation in the Films of Ingmar Bergman , Rochester, 1997.

Michaels, Lloyd, editor, Ingmar Bergman's Persona , New York, 1999; revised edition, Cambridge, 2000.

Articles:

Dyer, Peter John, in Sight and Sound (London), Spring 1958.

Whitebait, William, in New Statesman (London), 8 March 1958.

Powell, Dilys, in Sunday Times (London), 9 March 1958.

Rohmer, Eric, "Avec Le Septième Sceau Bergman nous offre son Faust," in Arts (Paris), 23 April 1958.

Mambrino, Jean, "Traduit du silence," in Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), May 1958.

Hart, Henry, in Films in Review (New York), November 1958.

Allombert, Guy, in Image et Son (Paris), February 1959.

Young, Colin, in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Spring 1959.

Archer, Eugene, "The Rack of Life," in Film Quarterly (Berkeley), Summer 1959.

Holland, Norman, "The Seventh Seal: The Film as Iconography," in Hudson Review (New York), Summer 1959.

Jarvie, Ian, "Notes on the Films of Ingmar Bergman," in Film Journal (Melbourne), November 1959.

Sarris, Andrew, in Film Culture (New York), no.19, 1959.

Time (New York), 14 March 1960.

Simon, John, "Ingmar, the Image-Maker," in Mid-Century (New York), December 1960.

Napolitano, Antonio, "Dal settimo sigillo alle soglie della vita," in Cinema Nuovo (Turin), May-June 1961.

Furstenau, Theo, "Apocalypse und Totentantz," in Die Zeit , 16 February 1962.

Cowie, Peter, in Films and Filming (London), January 1963.

Steene, Birgitta, "The Isolated Hero of Ingmar Bergman," in Film Comment (New York), September 1965.

Scott, James F., "The Achievement of Ingmar Bergman," in Journal of Aesthetics and Arts (Cleveland, Ohio), Winter 1965.

Bergman, Ingmar, in Film Comment (New York), Summer 1970.

Steene, Birgitta, "The Milk and the Strawberry Sequence in The Seventh Seal, " in Film Heritage (Dayton, Ohio), Summer 1973.

Helman, A., "Ingmar Bergman albo parabola pytan odwiecznych," in Kino (Warsaw), August 1974.

Wimberly, Darryl, in Cinema Texas Program Notes (Austin), 15 September 1977.

Malmkjaer, P., in Kosmorama (Copenhagen), Spring 1978.

Peary, Danny, in Cult Movies 2 , New York, 1983.

Pressler, M., "The Idea Fused in the Fact: Bergman and The Seventh Seal," in Literature/Film Quarterly (Salisbury, Maryland), April 1985.

Winterson, J., "Bloodied with Optimism," in Sight & Sound (London), vol. 1, May 1991.

Trasatti, S., "Bergman, il paradosso di un 'Ateo cristiano,"' in Castoro Cinema (Florence), November-December 1991.

" Det Sjunde inseglet Section" in Avant Scène du Cinéma (Paris), March 1992.

Lucas, Tim, in Video Watchdog (Cincinnati), vol. 33, 1996.

Merjui, Darius, "The Shock of Revelation," in Sight & Sound (London), vol. 7, no. 6, June 1997.

* * *

The Seventh Seal is one of the films in Ingmar Bergman's mature, highly individualized style, coming after an initial period he considers merely an imitative apprenticeship, in which he made films in the style of other directors. It was derived from a dramatic sketch, Wood Painting , which Bergman had written in 1954 for his drama students in Malmö. The Seventh Seal was made on a very low budget in 35 days.

In his late thirties, Bergman was still struggling with religious doubts and problems after having been reared very strictly in the Protestant Lutheran tradition, his father having been a prominent Swedish pastor. The Seventh Seal , which Bergman has termed an oratorio, is the first of three films (the others being The Face and The Virgin Spring ) made at this time in which he tried to purge the uglier aspects of religious practice and persecution, as well as confront the absence of any sign of response from God to human craving for help and reassurance. As the film makes clear at the beginning, the title refers to God's book of secrets sealed by seven seals; only after the breaking of the seventh seal will the secret of life, God's great secret, be revealed. In Bergman on Bergman he is quoted as saying, "For me, in those days, the great question was: Does God exist? or doesn't God exist?. . . If God doesn't exist, what do we do then? . . . What I believed in those days—and believed in for a long time—was the existence of a virulent evil, in no way dependent upon environmental or hereditary factors . . . an active evil, of which human beings, as opposed to animals, have a monopoly." He regards the 1950s as a period of personal convulsion, the remnants of his faith altering with a strengthening scepticism.

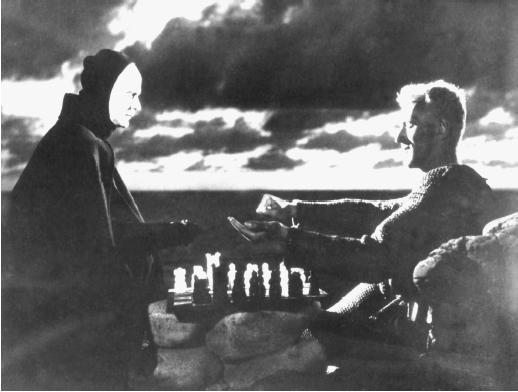

In The Seventh Seal , Antonius Blok, a 14th-century knight, returns home with his earthy, sensual squire, Jöns, after a decade of crusading in the Holy Land. He finds his native country plague-stricken and the people, haunted by a sense of guilt, given over to self-persecution, flagellation, and witch-hunting, a movement induced by a fantastic and sadistic monk, Raval. The Knight, God's servant-at-arms, finds that he has lost his faith and can no longer pray. In the midst of his spiritual turmoil, he is suddenly confronted by the personification of Death, a figure cloaked and implacable, who coldly informs him that his time has come. The Knight, unable to accept demise when in a state of doubt, wins a brief reprieve by challenging Death to a game of chess, the traditional ploy adopted by those seeking more time on earth, for Death is supposedly unable to resist such a challenge.

The film, Bergman has said, is "about the fear of death." Bergman had been steeped since childhood in the kind of imagery portrayed in this film, with its legendary concepts and simple pictorial forms; he had looked endlessly at the mural paintings that decorate the medieval Swedish churches. A painter of such images appears in the film, contriving studies of death to frighten the faithful. The stark but theatrical Christian imagery comes to life in The Seventh Seal . The Knight wins a brief reprieve, but Death still stalks his native land as the plague takes hold, and continues to haunt him with constant reappearances. The Knight demands:

Is it so cruelly inconceivable to grasp God with the senses? Why should he hide himself in a midst of half-spoken promises and unseen miracles? . . . What is going to happen to those of us who want to believe but aren't able to? . . . Why can't I kill God within me? Why does he live on in this painful and humiliating way even though I curse him and want to tear him out of my heart? . . . I want knowledge, not faith. . . . I want God to stretch out his hand toward me, reveal himself to me. . . . In our fear, we make an image and that image we call God.

But death has no answers, and God is silent. As for Jöns, he is faithful to his master, but cynical about the horrors of the Crusades: "Our crusade," he says, "was such madness that only a genuine idealist could have thought it up . . . . This damned ranting about doom. Is that good for the minds of modern people?" He prefers the simplicity of drink and fornication. To him Christianity is just "ghost stories."

In total contrast to the Knight's fearful dilemmas concerning faith and self-persecution is the position of Joff, a poor travelling entertainer and his beautiful young wife Mia. Joff, in his simplicity of heart, has continual visions of the Virgin and Child. Although Mia laughs lovingly at his excitement following the vision, she is happy to share his unquestioning faith. Only with these unpretentious people does the Knight find solace, "Everything I have said seems meaningless and unreal while I sit here with you and your husband," he says. Mia gives him milk and wild strawberries to eat, the latter symbols of spring or rebirth. It is, as Brigitta Steene suggests in her book on Bergman, a kind of private Eucharist which momentarily redeems the Knight from his doubts. It is only to be expected that Joff is hunted and persecuted by the puritanical and guilt-ridden religious community he seeks innocently to amuse.

At the close, when the chain-dance of Death tops the horizon, it is Joff and Mia who are spared by the Knight's intervention when he distracts Death while they escape. The Knight and his Lady have to accept death, and the squire can do nothing but go along with them. In a program note released with the film, Bergman wrote: "In my film the crusader returns from the Crusades as the soldier returns from war today. In the Middle Ages men lived in terror of the plague. Today they live in fear of the atomic bomb. The Seventh Seal is an allegory with a theme that is quite simple: man, his eternal search for God, with death as his only certainty."

Bergman has turned against this group of films, especially The Virgin Spring whose motivations he now finds "bogus." With its sparse, stylized, thematic dialogue, its austere sound effects, and its dignified melancholy music, The Seventh Seal survives as a compelling, if obsessive film, visually beautiful but permeated by the lighter as well as the darkest aspects of religious experience. It remains a powerful study in the cruelty of the religious impulse once it has soured in the human consciousness and merged with the darker aspects of the psyche. Bergman, at this spiritually troubled time in his life, was concerned with, "the idea of the Christian God as something destructive and fantastically dangerous, something filled with risk for the human being and bringing out in him the dark destructive forces instead of the opposite." Later, by 1960, he had adopted a more humanist position, and "life became much easier to live."

—Roger Manvell

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: