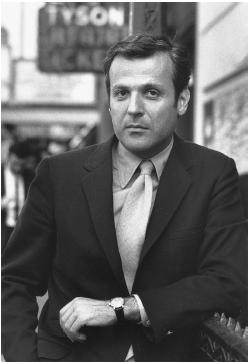

William Goldman - Writer

Writer. Nationality: American. Born: Chicago, Illinois, 12 August 1931; brother of the writer James Goldman. Education: Attended Highland Park High School; Oberlin College, Ohio, B.A. 1952; Columbia University, New York, M.A. 1956. Military Service: U.S. Army, 1952–54: corporal. Family: Married Ilene Jones, 1961 (divorced), two daughters. Career: Writer: first novel published 1957; author of two plays with James Goldman, Blood, Sweat, and Stanley Poole , 1961, and A Family Affair , 1962; 1964—first film as writer, Masquerade. Awards: Academy Award, Writers Guild Award, and British Academy Award, for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid , 1969; Academy Award and Writers Guild Award, for All the President's Men , 1976. Address: 50 East 77th Street, New York, NY 10021, U.S.A.

Films as Writer:

- 1964

-

Masquerade (Dearden) (co)

- 1966

-

Harper ( The Moving Target ) (Smight)

- 1969

-

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (Hill)

- 1972

-

The Hot Rock ( How to Steal a Diamond in Four Uneasy Lessons ) (Yates)

- 1974

-

The Stepford Wives (Forbes)

- 1975

-

The Great Waldo Pepper (Hill)

- 1976

-

All the President's Men (Pakula); Marathon Man (Schlesinger)

- 1977

-

A Bridge Too Far (Attenborough)

- 1978

-

Magic (Attenborough)

- 1979

-

Mr. Horn (Starrett); Butch and Sundance: The Early Days (Lester) (idea)

- 1987

-

Heat (Richards); The Princess Bride (R. Reiner)

- 1990

-

Misery (R. Reiner); The Lions of Salvo (de Palma)

- 1992

-

Year of the Comet (Yates); Memoirs of an Invisible Man (Carpenter) (co); Chaplin (Attenborough) (co)

- 1993

-

Last Action Hero (McTiernan) (co)

- 1994

-

Maverick (Donner)

- 1996

-

The Chamber (Foley) (co); The Ghost and the Darkness (Hopkins)

- 1997

-

Absolute Power (Eastwood); Fierce Creatures (Schepisi and Young) (uncredited)

- 1999

-

The General's Daughter (West) (co)

Films Based on Goldman's Writings:

- 1963

-

Soldier in the Rain (Nelson)

- 1968

-

No Way to Treat a Lady (Smight)

Publications

By GOLDMAN: fiction—

The Temple of Gold , New York, 1957.

Your Turn to Curtsy, My Turn to Bow , New York, 1958.

Soldier in the Rain , New York, 1960.

Boys and Girls Together , New York, 1964.

No Way to Treat a Lady , New York, 1964.

The Thing of It Is . . . , New York, 1967.

Father's Day , New York, 1971.

The Princess Bride , New York, 1973.

Marathon Man , New York, 1974.

Wigger (for children), New York, 1974.

Magic , New York, 1976.

Tinsel , New York, 1979.

Control , New York, 1982.

The Color of Light , New York, 1984.

The Silent Gondoliers , New York, 1984.

Heat , New York, 1985, as Edged Weapons , London, 1985.

Brothers , New York, 1986.

William Goldman: Four Screenplays , New York, 1997.

William Goldman: Five Screenplays, All the President's Men, Harper, The Great Waldo Papper, Magic & Maverick , New York, 1998.

By GOLDMAN: other writings—

With James Goldman, Blood, Sweat and Stanley Poole (play), New York, 1962.

With James Goldman, A Family Affair (play), New York, 1962.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (screenplay), New York, 1969.

The Season: A Candid Look at Broadway (nonfiction), New York, 1969.

The Great Waldo Pepper (screenplay), New York, 1975.

The Story of A Bridge Too Far, New York, 1977.

Adventures in the Screentrade: A Personal View of Hollywood and Screenwriting , New York, 1983.

With Mike Lupica, Wait till Next Year: The Story of a Season When What Should've Happened Didn't and What Could've Gone Wrong Did , New York, 1988.

Hype and Glory (nonfiction), New York, 1990.

The Big Picture: Who Killed Hollywood? And Other Essays , New York, 2000.

Which Lie Did I Tell? More Adventures in the Screen Trade , New York, 2000.

By GOLDMAN: articles—

Films Illustrated (London), July 1976.

Filmmakers Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), October 1977.

In The Craft of the Screenwriter , by John Brady, New York, 1981.

Films (London), May 1984.

Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), February 1991.

Positif (Paris), no. 361, March 1991.

Disaster Movies , no. 38, New York, 1992.

Cinema 66 , no. 20, New York, 1993.

Sins of Omission , no. 6, New York, 1993.

"Butch Cassidy and the Nazi Dentist," no. 5, Esquire , 1994.

The Pig and the Hunk , no. 8, New York, 1996.

"Tracking The Ghost and the Darkness ," in Premiere (Boulder), November 1996.

"From Brando to Paltrow," in Premiere (Boulder), December 1996.

Film en Televisie + Video (Brussels), July 1997.

"William Goldman on Norman Jewison," in The Toronto Star , 18 April 1999.

"The Gray '90s: Nobody Knows Anything," in Premiere (Boulder), November 1999.

On GOLDMAN: book—

Andersen, Richard, William Goldman , Boston, 1979.

On GOLDMAN: articles—

American Film (Washington, D.C.), January/February 1976.

Cinéma (Paris), August/September 1977.

Cinéma (Paris), August/September 1978.

National Film Theatre Booklet (London), April 1984.

Stone, Botham, in American Screenwriters, 2nd series , edited by Randall Clark, Detroit, 1986.

Radio Times (London), 19 February 1994.

Feeney, Mark, "The Goldman Standard: Oscar-Winning Screenwriter Says It's Easy: Work Hard, Stay Scared, and Above All Be Lucky," in The Boston Globe , 8 March 2000.

Welkos, Robert W. "Profile: He Knows They Don't Know," in The Los Angeles Times , 2 April 2000.

Sragow, Michael, "Famous Screenwriters School," in The New York Times Book Review , 9 April 2000.

* * *

William Goldman is a master craftsman of streamlined scripts with well-delineated characters and crisp dialogue. For Goldman, screenwriting is carpentry. "The single most important thing contributed by the screenwriter," he once said, "is the structure." Accordingly, Goldman's scripts are fast-paced models of plot design.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid was an important screenplay even before it was produced. In 1967 it sold for the then unheard-of price of $400,000, setting an industrial precedent that helped American screenwriters gain recognition and clout. The film was extremely popular, but suffered critically in comparison with Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch , released a few months earlier. Where The Wild Bunch was a gritty, intensely graphic revisionist Western, Butch Cassidy appeared lightweight, flip, and coy. And Butch Cassidy 's freeze-frame ending (which came directly from Goldman's script) seemed tame and retrograde compared to The Wild Bunch 's apocalyptic bloodbath. But for all its cuteness, Butch Cassidy was revisionist too. Goldman's heroes were imperfect (Sundance cannot swim, and Butch, notorious leader of the Hole in the Wall Gang, confesses he has never killed anyone) and drawn on a human rather than heroic scale (Butch and Sundance spend most of the film running away from the railroad agents, strenuously avoiding the obligatory Western confrontation). Goldman parodied train robberies, bank holdups, and tightlipped face-offs. He made a joke of the gathering-of-the-posse scene (de rigueur since The Great Train Robbery ) by writing one in which the local marshal fails to persuade the townsfolk to rush out after Butch and Sundance. ("It's up to us to do something!" exhorts the marshal. "What's the point?" answers one uninterested citizen.) Perhaps most revisionist of all was Goldman's arch, smart-alecky dialogue. Having his characters speak like witty urbanites was an experiment that might have failed, but it worked, and its originality was no small part of the film's charm. If The Wild Bunch madeus think about violence in Westerns, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid made us question Western conventions.

Although Goldman has adapted other authors' works as well as his own, he is not, by his own admission, ruthless enough when the source is his. This may account for the absence of Goldman's usually hard-driving plotting in Marathon Man and Magic , both adapted from his best-selling novels. Szell's torturing of Babe with a dental drill is unforgettable, but the main action in Marathon Man is muddled. Magic develops some keen moments of tension, but it fizzles where it should pop, and pales badly in comparison with its generic ancestor, Michael Redgrave's ventriloquist sequence in Dead of Night. But in adapting others' works for the screen Goldman is expert. Indeed, it seems the longer and more intricate the original, the better his final script. His adaptations for A Bridge Too Far and All the President's Men , both based on nonfiction books about complex historical events, are clean and economical translations, especially considering the problems he faced.

In A Bridge Too Far Goldman was required to make commercially palatable what was essentially a noncommercial property. Cornelius Ryan's book documented a crucial but (in the United States) little-known Allied operation that defies simple summarization (unless it would be "We lost"). Goldman cut through the book's tangled historical web and provided an easily understood, straight-line narrative by making the film, as he says, "the ultimate cavalry-to-the-rescue story": the Allies need to take a series of bridges and relieve 35,000 soldiers who have parachuted in behind enemy lines. But the loss suffered by the Allies when they came up one bridge short of their objective dictated a deflated ending, which no doubt had something to do with the film's disappointing reception.

In All the President's Men Goldman had to find a way to interest audiences in a talky political story, lacking in action and climactic confrontations, with an ending viewers already knew. Goldman's solution was to model the film on late 1940s-early 1950s investigative reporter films noir (Goldman's script preface specified that the film should have "a black-and-white feel") and give it racehorse pacing (another prefatory script note: "This film is written to go like a streak"). He structured the film as a dramatic progression of clues uncovered by the giant-killing investigators, Woodward and Bernstein, and built a solid foundation for a gripping thriller.

Goldman is a pragmatic professional about his work and about the baroque process of going from script to screen. In Adventures in the Screen Trade Goldman looks at the movie business sans rose-colored glasses and comes up with screenwriting rules of thumb such as what he considers to be the key movie industry fact: "NOBODY KNOWS ANYTHING." And there is this clear-eyed observation, which may explain why Goldman continues to describe himself as a novelist who writes screenplays rather than the other way around. This thoroughly professional screenwriter feels that in the final analysis screenwriting—because of built-in industrial limitations—will ruin a serious writer. "I truly believe," Goldman writes, "that if all you do with your life is write screenplays, it ultimately has to denigrate the soul. . . . Because you will spend your always-decreasing days . . . writing Perfect Parts for Perfect People."

During the first half of the 1980s, Goldman went through a fallow period when none of his scripts were produced. However, these doldrums ended in 1986, when Goldman sold his screenplay of The Princess Bride (based on his 1973 novel of the same name). He remained busy throughout the decade of the 1990s (a period whose films Goldman has characterized as the most lackluster in the history of American cinema) and beyond. In the spring of 2000, he published two nonfiction books. Which Lie Did I Tell? More Adventures in the Screen Trade was a sequel to Goldman's popular 1983 memoir, Adventures in the Screen Trade. The second book, The Big Picture: Who Killed Hollywood? And Other Essays collects short pieces that Goldman originally wrote for Premiere and other popular magazines.

—Charles Ramirez Berg, updated by John McCarty, further updated by Justin Gustainis

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: