Ray Harryhausen - Writer

Special Effects Technician and Director. Nationality: American. Born: Los Angeles, California, 19 June 1920. Education: Attended Los Angeles City College. Military Service: Served in the Signal Corps during World War II. Career: Animator for Puppetoons series for George Pal in early 1940s; 1953—first film as special effects technician, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms ; developed model animation process Dynamation; 1955—began partnership with Charles H. Schneer; 1980s—retired. Awards: Gordon E. Sawyer Award for Technical Achievement, 1992.

Films as Director and Producer:

(shorts)

- 1946

-

Mother Goose Presents Humpty Dumpty ( Little Miss Muffet ; Old Mother Hubbard ; The Queen of Hearts ; The Story Book Review )

- 1949

-

Story of Little Red Riding Hood ; Mighty Joe Young (Schoedsack) (asst)

- 1951

-

The Story of Hansel and Gretel ( Rapunzel )

- 1953

-

The Story of King Midas

Films as Special Effects Technician:

- 1953

-

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (Lourié)

- 1955

-

It Came from beneath the Sea (Gordon); The Animal World (Allen)

- 1956

-

Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (Sears)

- 1957

-

20 Million Miles to Earth (Juran) (+ co-sc)

- 1958

-

The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad (Juran) (+ story)

- 1960

-

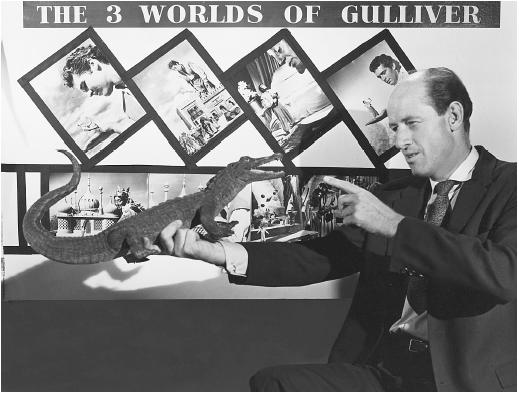

The Three Worlds of Gulliver (Sher)

- 1961

-

Mysterious Island (Endfield)

- 1963

-

Jason and the Argonauts (Chaffey) (+ assoc pr)

- 1964

-

First Men in the Moon (Juran)

- 1966

-

One Million Years B.C. (Chaffey)

- 1969

-

The Valley of Gwangi (O'Connolly) (+ assoc pr)

- 1973

-

The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (Hessler) (+ assoc pr)

- 1977

-

Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (Wanamaker) (+ assoc pr)

- 1981

-

Clash of the Titans (Davis) (+ co-pr)

- 1986

-

The Puppetoon Movie (Warren)

Film as Actor:

- 1985

-

Spies Like Us (Landis) (as Dr. Marston)

- 1994

-

Beverly Hills Cop III (Landis) (as Bar Patron)

- 1997

-

Flesh and Blood (Newsom) (as himself)

- 1998

-

Mighty Joe Young (Underwood) (as Gentleman at the Party)

Publications

By HARRYHAUSEN: book—

Film Fantasy Scrapbook , South Brunswick, New Jersey, 3 vols., 1974–81.

By HARRYHAUSEN: articles—

Kinoscope , vol. 3, no. 1, 1968.

L'Incroyable Cinéma (Salford, Warwickshire), Autumn 1971.

Cinema TV Today (London), 28 July 1973.

Film (London), October 1973.

Cinema Papers (Melbourne), January 1974.

Special Visual Effects , Spring 1974.

Millimeter (New York), April 1974.

Film Review (London), September 1975.

Horror Elite , September 1975.

Film Making , May 1976.

Filmmakers Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), September 1977.

Cinefantastique (New York), Fall 1977.

Film Comment (New York), November/December 1977.

Ecran Fantastique (Paris), no. 12, 1980.

Starburst (London), no. 35, 1981.

Ecran Fantastique (Paris), no. 20, 1981.

American Cinematographer (Hollywood), June 1981.

American Film (Washington, D.C.), June 1981.

Cinefex (Riverside, California), July 1981.

Photoplay (London), October 1981.

Positif (Paris), December 1981.

Filmcritica (Rome), April 1982.

Cinema e Cinema (Bologna), January/March 1983.

Movie Maker (Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire), September 1983.

Revue du Cinéma (Brussels), May 1992.

Filmfax (Evanston), September-October 1995.

On HARRYHAUSEN: articles—

Midi-Minuit Fantastique (Paris), June 1963.

Cinéma (Paris), no. 113, 1967.

Photon (New York), no. 25, 1974.

Take One (Montreal), vol. 4, no. 8, 1974.

Cinefantastique (New York), Spring 1974.

In The Saga of Special Effects , by Ron Fry and Pamela Fourzon, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1977.

Vampir (Nuremberg), March 1977.

Starburst (London), no. 27, 1980.

Banc-Titre (Paris), January 1980.

Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), November 1980.

Cinefantastique (New York), Winter 1980.

National Film Theatre Booklet (London), July 1981.

Cinefantastique (New York), Fall 1981.

Films in Review (New York), October 1981.

Cinefantastique (New York), December 1981.

Classic Images (Muscatine, Iowa), January 1984.

Movie Maker (Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire), March 1985.

American Cinematographer , vol. 73, 1992.

Entertainment Weekly (New York), 23 September 1994.

Outré (Evanston), vol. 1, no. 4, 1995.

Scarlet Street (Glen Rock), vol. 23, 1996.

* * *

From the 1950s until his retirement in the 1980s, Ray Harryhausen set the standards for stop-motion animation effects in film. Influenced as a child by Willis O'Brien's King Kong , Harryhausen contacted O'Brien in the late 1940s and worked with him on Mighty Joe Young , finally doing most of the animation for that production. He also worked with George Pal in the Puppetoons series of children's short films.

His big break came when he provided, for a minimal budget, the special effects for The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms . The rhedosaurus that attacked an amusement park was impressive, and it established Harryhausen's reputation. Three low-budget, black-and-white science-fiction films followed. In It Came from beneath the Sea Harryhausen created a giant octopus with five tentacles that attacked San Francisco and wrapped itself around the Golden Gate bridge; the fluid motion of the octopus and its integration with live-action shots made it a believable fantasy. This film was also Harryhausen's first collaboration with the producer Charles Schneer, a working relationship that lasted for a quarter of a century. Although the second of these films, Earth vs. the Flying Saucers , was made primarily to capitalize on the paranoia of the 1950s, Harryhausen's special effects brought some originality to what was otherwise a standard plot and mediocre characterization. In this film Harryhausen was challenged to make interesting an inanimate, virtually featureless, spaceship, and he succeeded in conveying menace while giving almost no views of the aliens. The opening sequence, when a flying saucer swoops down behind a car on a lonely desert highway is a classic example of alien paranoia. The most interesting of the three films is 20 Million Miles to Earth , in which a Venusian Ymir grows rapidly and menaces the Italian countryside. Like King Kong in many ways, the Ymir is Harryhausen's most sympathetic monster. These early black-and-white films, even with their low budgets, often have a more unified plot and adult point of view than the later family films, which were technically more advanced but episodic. In his last strictly science-fiction film, First Men in the Moon , Harryhausen tackled the challenges of widescreen and color to bring H. G. Wells's period novel successfully to the screen. Willis O'Brien had made The Lost World , and Harryhausen also created prehistoric creatures for his heroes to battle in Mysterious Island , One Million Years B.C. , and The Valley of Gwangi . Gwangi failed to be the box-office success that its creators expected from its unique combination of cowboys and dinosaurs.

Harryhausen's most popular films have been the "voyage" productions with Gulliver and Sinbad. All of these are episodic narratives with interchangeable plots in which the hero sets sail to aid a beautiful girl, right a wrong, or achieve some personal goal; but each film has outstanding examples of animation—the skeleton fight in The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad , the six-armed Kali of The Golden Voyage of Sinbad , the Minotaur or troglodyte in Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger . Harryhausen focused on Greek mythology in two films, although mythological elements and figures show up in a number of other productions. With Jason and the Argonauts he came closest to capturing the power of myth; in the creaking movements of the statue Talos, in the attack of the harpies, and in Jason's fight with seven skeletons, he captures this sense of awful magic without reducing it to a child's point of view.

No one who works in science-fiction or fantasy films can escape the influence of Ray Harryhausen, and works as diverse as Flesh Gordon and The Empire Strikes Back draw upon techniques he perfected. Yet Harryhausen, for a number of reasons, has often been seen as a technician rather than as an artist. First, he has worked exclusively in the science-fiction/fantasy genres, an area considered unimportant by many film critics and scholars. Further, his biggest box-office successes have been directed toward children and have avoided the darker sides of fantasy that can enrich and give depth to the genre. Last, episodic scripts, often with banal dialogue and uninspired acting, have detracted from his special effects work. Yet Harryhausen's animation scenes are unique, and long after the weaker parts of the films have faded away, the best of them remain in the viewer's mind to exemplify a special kind of cinema magic.

—Leonard G. Heldreth

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: