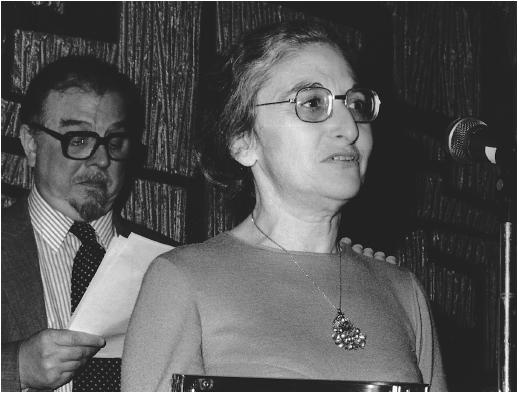

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala - Writer

Writer. Nationality: American. Born: Cologne, Germany, of Polish parents, 7 May 1927; emigrated to England as a refugee, 1939; naturalized, 1948; became U.S. citizen, 1986. Education: Attended Hendon County School, London; Queen Mary College, University of London, M.A. in English literature 1951. Family: Married Cyrus Jhabvala, 1951, three daughters. Career: Lived in India, 1951–75; published her first novel, To Whom She Will , 1955; began her association with producer Ismail Merchant and director James Ivory, by scripting The Householder , 1963; moved to New York, 1975. Awards: Booker Prize, 1975; Best Adapted Screenplay British Academy Award, for Heat and Dust , 1983; Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium Academy Award, Writers Guild of America Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium, for A Room with a View , 1986; New York Film Critics Circle Best Screenplay, for Mr. and Mrs. Bridge , 1990; Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium Academy Award, for Howards End , 1992; Writers Guild of America Laurel Award for Screenwriting Achievement, 1994; Writers Award Gotham Award, 1997. Address: 400 East 52nd Street, New York, NY 10022, U.S.A.

Films as Writer for Director James Ivory:

- 1963

-

The Householder

- 1965

-

Shakespeare Wallah

- 1968

-

The Guru

- 1970

-

Bombay Talkie

- 1975

-

Autobiography of a Princess (co)

- 1977

-

Roseland

- 1978

-

Hullabaloo over Georgie and Bonnie's Pictures

- 1979

-

The Europeans

- 1980

-

Jane Austen in Manhattan

- 1981

-

Quartet

- 1983

-

Heat and Dust

- 1984

-

The Bostonians

- 1986

-

A Room with a View

- 1990

-

Mr. and Mrs. Bridge

- 1992

-

Howards End

- 1993

-

The Remains of the Day

- 1995

-

Jefferson in Paris

- 1996

-

Surviving Picasso

- 1998

-

A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries (co-sc)

- 2000

-

The Golden Bowl

Other Films as Writer:

- 1982

-

The Courtesans of Bombay (Merchant) (doc)

- 1988

-

Madame Sousatska (Schlesinger) (co-sc)

Publications

By JHABVALA: fiction—

To Whom She Will , London, 1955, as Amrita , New York, 1956.

The Nature of Passion , London, 1956.

Esmond in India , London, 1958.

The Householder , London, 1960.

Get Ready for Battle , London, 1962.

Like Birds, Like Fishes and Other Stories , London, 1963.

A Backward Place , London, 1965.

A Stronger Climate: Nine Stories , London, 1968.

An Experience of India , London, 1971.

A New Dominion , London, 1972, as Travelers , New York, 1973.

Heat and Dust , London, 1975.

How I Became a Holy Mother and Other Stories , London, 1976.

In Search of Love and Beauty , London, 1983.

Out of India: Selected Stories , New York, 1986.

Three Continents , London, 1987.

Poet and Dancer , London, 1993.

Shards of Memory , London, 1995.

East into Upper East: Plain Tales from New York and New Delhi , Washington, D.C., 1998.

Travelers , Washington, D.C., 1999.

By JHABVALA: other books—

Meet Yourself at the Doctor (nonfiction), London, 1949.

Shakespeare Wallah (screenplay), London, 1973.

Autobiography of a Princess (screenplay), London, 1975.

By JHABVALA: articles—

Sight and Sound (London), Winter 1978–79.

Interview (New York), December 1983.

On JHABVALA: books—

Williams, H. M., The Fiction of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala , Calcutta, 1973.

Shahane, Vasant A., Ruth Prawer Jhabvala , New Delhi, 1976.

Gooneratne, Yasmine, Silence, Exile, and Cunning: The Fiction of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala , New Delhi, 1983.

Pym, John, The Wandering Company , London, 1983.

Sucher, Laurie, The Fiction of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala , London, 1989.

Bailur, Jayanti, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala: Fiction & Film , 1992.

Chakravarti, Arauna, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala: A Study in Empathy & Exile , Delhi, 1998.

On JHABVALA: articles—

" Quartet Issue" of Avant-Scène (Paris), 1 October 1981.

Film Dope (Nottingham), July 1983.

Firstenberg, J., "A Class Act Turns Twenty-Five," in American Film , September 1987.

Variety (New York), 28 October/3 November, 1996.

Yunis, Alia, "Ruth Prawer Jhabvala: Writer With a View," in Script (Baldwin, Maryland), vol. 5, no. 6, 1996.

* * *

Since the 1960s, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala has enjoyed a unique position among screenwriters as one of the principal collaborators in Merchant Ivory Productions, the independent film company headed by the Indian producer Ismail Merchant and the American director James Ivory. Jhabvala has supplied the scripts for a majority of the company's productions, in a happy blend of narrative styles and thematic concerns that has proven so seamless it is often difficult to tell where the writer's influence ends and the filmmaker's begins.

Jhabvala was born in Germany and emigrated with her parents to England in 1939. She later married the architect Cyrus Jhabvala and moved with him to India, where she lived for 24 years. (She eventually was to divide her time between India and New York City.) Her life in India became the source of many of her richest earliest works, and fostered within her a fascination with the country that she shares with Ivory. Beginning with The Householder , an adaptation of one of her own novels, Jhabvala wrote a series of films for Merchant Ivory Productions which helped establish both the company itself and James Ivory's reputation as a director. All of these films are set in India and deal with cultural clashes of one kind or another, a theme that would become a hallmark of the company's output. The best known of the group, Shakespeare Wallah , follows the fortunes of a British touring theatrical company, sadly out of place in modern India yet determined to hang on to their traditional way of life. Conflicts between East and West, tradition and change, or simply different strata of the same society recur throughout the Jhabvala-Ivory collaborations, with the stories' characters trying—and often failing—to reconcile themselves to their differences in culture and class.

Ivory's films are exquisite, leisurely portraits of minutely observed people and places, and Jhabvala's screenplays lend themselves admirably to the director's style. Subtle nuances of dialogue reveal shifts in a character's thoughts or emotions, while the story is allowed to unfold through delicately sketched character interaction rather than dynamic physical activity. The themes that mark the team's earliest films were applied on a more diverse scale in their collaborations between the mid-1970s and mid-1980s, with The Europeans , adapted from Henry James's novel, exploring the conflicts between British and American culture; The Bostonians , again adapted from James, examining the problematic interplay between men and women; and Roseland depicting the gulf between reality and imagination in its stories of the people who frequent an outmoded New York ballroom. Autobiography of a Princess and Heat and Dust find Jhabvala and Ivory returning again to the Anglo-Indian cultural conflict, with a particular emphasis on the differences between present-day India and the India of the British Raj.

Merchant-Ivory's 1986 adaptation of E. M. Forster's A Room with a View introduced new audiences to the style of filmmaking that had won them a hitherto select—but devoted—following. Its story of a young Englishwoman's emotional and sexual awakening in the face of the beauty and passion of Florence was ideally suited to Ivory's and Jhabvala's long-standing concerns. The latter's witty, literate script is alive with carefully shaded characterizations. The same can be said for Howards End , also based on Forster, which explores class distinctions in 1910 England (and is considered the penultimate Merchant-Ivory-Jhabvala collaboration); and The Remains of the Day , adapted from Kazuo Ishiguro's novel, about an efficient, mindlessly selfless professional servant, in which most of the narrative occurs between the world wars. Less successful (but no less ambitious) were Mr. and Mrs. Bridge (about the manner in which the passage of time affects a Midwestern couple); Jefferson in Paris (chronicling Thomas Jefferson's experiences while serving as the U.S. ambassador to France); and Surviving Picasso (the based-on-fact account of Francoise Gilot, a young artist who becomes the lover of an egotistical, womanizing Pablo Picasso). Jhabvala's final Merchant-Ivory film of the 1990s, A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries , is an improvement over their most recent collaborations. Based on the autobiographical novel by Kaylie (daughter of James) Jones, it is the heartfelt, though somewhat episodic, account of a famed expatriate novelist and his familial bonds. Despite its flaws, A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries is a rarity in contemporary cinema in that it offers a portrait of a loving, non-dysfunctional family.

In the 1990s, the ever-thinning line between Hollywood and the world of independent cinema may be best symbolized by Merchant-Ivory's inking a three-film pact with the Walt Disney Company. Nonetheless, despite their artistic lapses, Merchant-Ivory—and Jhabvala—have sustained the conviction that the tradition of the intelligent, thoughtful film, brimming with observations on the complexities of human nature—a conviction that seems so out of place in contemporary Hollywood—remains safe and alive in their hands.

—Janet Lorenz, updated by Rob Edelman

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: