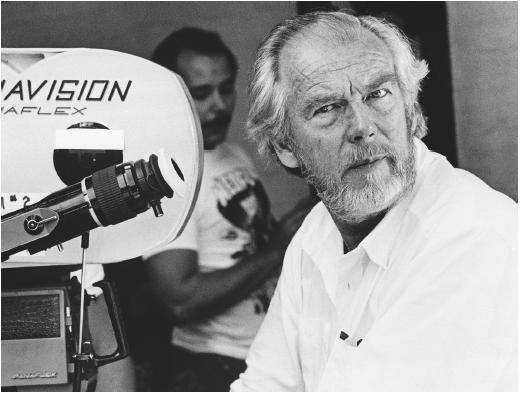

Sven Nykvist - Writer

Cinematographer and Director.

Nationality:

Swedish.

Born:

Moheda, 3 December 1922.

Family:

Father of the director-writer Carl-Gustav Nykvist.

Career:

Assistant cameraman from early 1940s; 1945—first film as

cinematographer; 1953—first of many films for Ingmar Bergman,

The Naked Night

; 1956—co-directed first film,

Gorilla

; 1996—cinematographer for TV mini-series

Enskilda samtal.

Awards:

Best Cinematography Academy Award and National Society of Film Critics

Best Cinematography Award, for

Cries and Whispers

, 1972; Jury Specialbagge Guldbagge Award, 1973; Best Cinematography Cesar

Award, for

Black Moon

, 1975; Best Cinematography Academy Award, Best Cinematography British

Academy Award, Best Cinematography British Society of Cinematographers,

Los Angeles Film Critics Association Best Cinematography, for

Fanny and Alexander

, 1982; Cannes Film Festival Best Artistic Contribution, for

The Sacrifice

, 1986; Best Cinematography Independent Spirit Award, for

The Unbearable Lightness of Being

, 1988; Camerimage Lifetime Achievement Award, 1993; American Society of

Cinematographers Lifetime Achievement Award, 1996; Camerimage Special

Award (shared with Ingmar Bergman), 1998.

Films as Cinematographer:

- 1941

-

The Poor Millionaire (asst)

- 1945

-

Barnen från Frostmofjället ( The Children of Frostmofjället ) (Husberg) (asst); Gomorron Bill (Falk-Winner); Tretton stolar ( Thirteen Chairs ) (Larsson)

- 1946

-

Saltstänk och krutgubbar (Bauman)

- 1947

-

Maj på Malö (Bauman); Lata Lena och blåögda Per (Wallén)

- 1949

-

Lång-Lasse i Delsbo (Johansson); Hin och smålänningen (co); Bohus bataljon (Cederstrand-Spjuth); Sjösalavår ( Spring at Sjösala ) (Wallén)

- 1950

-

Loffe blir polis (Ahrle) (co)

- 1951

-

Rågens rike (Johansson)

- 1952

-

Under Södra Korset ( Under the Southern Cross ) (+ co-d, co-sc—doc); Nar syrenerna blommar ( When Lilacs Blossom ) (Johansson)

- 1953

-

Barabbas (Sjöberg) (co); Vägen till Kolckrike (Skoglund); > Gycklarnas afton ( The Naked Night ; Sawdust and Tinsel ) (Bergman) (co)

- 1954

-

Salka Valka (Mattsson); Karin Mansdotter (Sjöberg); Storm over Tjurö (Mattsson)

- 1955

-

Sista ringen (Skoglund); Den underbara lögnen (Road)

- 1956

-

Gorilla (+ co-d); Nattbarn ( Children of the Night ) (Hellström); Flickan i frack ( Girl in a Dressing Gown ) (Mattsson); Blänande hav (Skoglund); Alskling på vågen (Bauman) (co); Ett kungligt äventyr (Birt); Den tappre soldaten Jönsson (Bergström)

- 1957

-

En drömmares vandring ( A Dreamer's Walk ) (Lindgren); Gäst i eget hus (Olin); Synnöve Solbakken (Hellström)

- 1958

-

Damen i svart ( Lady in Black ) (Mattsson); Laila—Liebe unter der Mitternachtssonne ( Make Way for Lila ) (Husberg)

- 1959

-

Får jag låna din fru? (Mattsson)

- 1960

-

Jungfrukällan ( The Virgin Spring ) (Bergman); Domaren ( The Judge ) (Sjöberg); De sista stegen ( A Matter of Morals ) (Cromwell)

- 1961

-

Sasom i en spegel ( Through a Glass Darkly ) (Bergman)

- 1963

-

Nattsvardsgästerna ( Winter Light ; The Communicants ) (Bergman); Tystnaden ( The Silence ) (Bergman)

- 1964

-

För att inte talla om all dessa kvinnor ( All These Women ; Now about All These Women ) (Bergman); Att älska ( To Love ) (J. Donner); Alskande par ( Loving Couples ) (Zetterling)

- 1965

-

Lianbron ( The Vine Bridge ) (+ d)

- 1966

-

Persona (Bergman)

- 1968

-

Vargtimmen ( Hour of the Wolf ) (Bergman); Skammen ( The Shame ) (Bergman)

- 1969

-

Riten ( The Ritual ; The Rite ) (Bergman); En passion ( The Passion of Anna ; Passion ) (Bergman)

- 1970

-

Erste Liebe ( First Love ) (Schell)

- 1971

-

Beröringen ( The Touch ) (Bergman); The Last Run (Fleischer); One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (Wrede)

- 1972

-

Viskningar och rop ( Cries and Whispers ) (Bergman); Siddhartha (Rooks)

- 1973

-

Scener ur ett äktenskap ( Scenes from a Marriage ) (Bergman)

- 1974

-

The Dove (Jarrott); Ransom ( The Terrorists ) (Wrede); Trollflöjten ( The Magic Flute ) (Bergman)

- 1975

-

Black Moon (Malle)

- 1976

-

Ansikte not ansikte ( Face to Face ) (Bergman); Le Locataire ( The Tenant ) (Polanski)

- 1977

-

Das Schlangenei ( The Serpent's Egg ) (Bergman)

- 1978

-

En och en ( One Plus One ) (+ co-d); Pretty Baby (Malle); King of the Gypsies (Pierson); Herbstsonate ( Autumn Sonata ) (Bergman)

- 1979

-

Hurricane (Troell); Starting Over (Pakula)

- 1980

-

Willy and Phil (Mazursky); Aus dem Leben der Marionetten ( From the Life of the Marionettes ) (Bergman)

- 1981

-

The Postman Always Rings Twice (Rafelson)

- 1982

-

Fanny och Alexander ( Fanny and Alexander ) (Bergman); Cannery Row (Ward)

- 1983

-

Un Amour de Swann ( Swann in Love ) (Schlondörff); La Tragédie de Carmen ( The Tragedy of Carmen ) (Brook); Star 80 (Fosse)

- 1984

-

Efter Repetitioner ( After the Rehearsal ) (Bergman)

- 1985

-

Agnes of God (Jewison)

- 1986

-

Offret ( The Sacrifice ) (Tarkovsky)

- 1988

-

The Unbearable Lightness of Being (Kaufman); Another Woman (W. Allen); Katinka ( Vid Vgen ; Ved Vejen ) (von Sydow)

- 1989

-

Crimes and Misdemeanors (W. Allen); "Oedipus Wrecks" ep. of New York Stories (W. Allen)

- 1991

-

Buster's Bedroom (Horn)

- 1992

-

Chaplin (Attenborough)

- 1993

-

What's Eating Gilbert Grape (Hallström); Sleepless in Seattle (N. Ephron)

- 1994

-

With Honors (Keshishian); Only You (Jewison); Mixed Nuts (N. Ephron)

- 1995

-

Something to Talk About (Hallström); Kristin Lavransdotter (Ullmann)

- 1996

-

Enskilda samtal ( Private Conversation ) (Ullmann—mini for TV)

- 1998

-

Celebrity (Allen)

- 1999

-

Curtain Call (Yates)

Other Films:

- 1977

-

A Look at Liv (Kaplan) (doc) (ro as Himself)

- 1992

-

The Ox (d, sc)

- 1992

-

Visions of Light: The Art of the Cinematographer (Glassman, McCarthy, Samuels) (doc) (ro as Interviewee)

- 1995

-

Lumiere et compagnie ( Lumiere and Company ) (various) (ro)

- 1997

-

Liv Ullmann scener fra et liv (Hambro) (doc) (ro as Interviewee)

- 2000

-

Ljuset haller mig sallskap ( Light Keeps Me Company ) (Carl-Gustav Nykvist) (doc) (ro as Interviewee)

Publications

By NYKVIST: articles—

"Photographing the Films of Ingmar Bergman," in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), October 1962.

"A Passion for Light," in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), April 1972.

Chaplin (Stockholm), no. 5, 1973.

Deutsche Kameramann (Munich), September 1974.

On The Magic Flute in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), August 1975.

On Face to Face in Filmmakers Newsletter (Ward Hill, Massachusetts), May 1976.

Filmkritik (Munich), May 1976.

Millimeter (New York), July/August 1976.

On Cannery Row in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), April 1981.

Millimeter (New York), May 1981.

On Location (Hollywood), November 1983.

American Film (Washington, D.C.), March 1984.

Stills (London), June/July 1984.

Eyepiece (London), July/August 1984.

Positif (Paris), May 1986.

Positif (Paris), February 1988.

American Cinematographer (Hollywood), March 1989.

Film Comment (New York), September/October 1989.

Time Out (London), 7 April 1993.

On NYKVIST: articles—

Filmwoche , 8 July 1961.

Chaplin (Stockholm), December 1965.

Film in Sweden , no. 1, 1968.

Film World (Bombay), October/December 1968.

Focus on Film (London), Winter 1970; corrections in no. 13, 1973.

Eder, R., in New York Times , 7 April 1976.

Denby, D., in New York Times , 25 April 1976.

On From the Life of the Marionettes in Film (London), 15 November 1982.

Curtin, J., in New York Times , 12 June 1983.

Block, Bruce A., in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), April 1984.

Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), no. 385, June 1986.

Film Dope (Nottingham), July 1992.

Chaplin (Stockholm), vol. 34, no. 6, 1992/1993.

Filmkultura (Budapest), July 1993.

Fisher, B., "ASC salutes Sven Nykvist," in American Cinematographer (Hollywood), February 1996.

Edmunds, M., "A master lenser looks back," in Variety (New York), 17–23 February 1997.

Fujiwara, Chris, "Soulful Eye," in Boston Phoenix , 18–25 May 2000.

* * *

Sven Nykvist's color cinematography on the films of the director Ingmar Bergman has won him praise, awards—and endless imitators. Nykvist was the director of photography on all of Bergman's films and most of his television productions from The Virgin Spring through Fanny and Alexander and After the Rehearsal. So well does Nykvist's cinematography fit Bergman's later films that it is difficult to untangle their mutual influence on each other's work.

When he was part of Bergman's tightly knit 18-person crew, Nykvist's responsibilities included lighting and actually working the camera, as well as designing the cinematography for the production. This may account for the decline in quality (from superb down to excellent) when Nykvist works on American films, and must delegate part of his duties among the crew. Nevertheless, there is also clearly a symbiotic matching of tastes and temperaments between himself and Bergman that Nykvist has not shared with other directors. Both Swedes are the sons of pastors, both had difficult childhoods (Nykvist's parents were African missionaries, and left him at home in Sweden for much of his childhood), and both fondly recall an early fascination with the power of film and light over the imagination.

Nykvist's pioneering with natural light sources complements Bergman's penchant for location shooting and minimalist shot compositions ("two faces and a teacup"). While Nykvist builds upon the Swedish tradition of filmmaking in his style, he has brought the national tradition of stark psychological landscape into international favor with color cinematography that achieves iconographical beauty by eschewing the distracting prettiness generally associated with color film. Initially, Nykvist was reluctant to move from black and white to color because color's tendency to prettify subjects and emphasize detail made it difficult to show something as convincingly "ugly." When color became a commercial necessity, Nykvist and Bergman got off to a false start in Now about All These Woman , released in 1964, which made them run for cover back to black and white until they shot Passion in 1969. By ignoring much of the conventional wisdom about using color film, Nykvist finally managed to bring an iconographical style to Cries and Whispers , his fourth color film for Bergman.

Nykvist emphasizes that he strives for realism, but his use of the term is misleading. He portrays psychological truth rather than social realism, and his heavy reliance on natural light and geometrically precise shot composition gives his work the convincing quality of a dream, not a documentary. Nykvist explains that light is the key to his cinematography, and that light is a character in Bergman's films. The significance of an actor's actions often is determined by subtle differences in lighting. This fascination with light is probably linked to both men's experience of Sweden's sunless winters and unblinking summer sun. On Cries and Whispers the two men spent weeks simply gauging the natural light at different times of day inside the house which served as the main interior for the film. This careful preproduction work in terms of light is typical of their style.

Although each of Nykvist's films for Bergman has its own unique look, Nykvist typically favors a soft bounce lighting. Careful positioning of highlights prevents the usual flattening effect of such lighting, and gives actors a rounded, three-dimensional look which is flattering. He uses a minimum of color saturation, and sets and costumes are usually chosen in muted tones. In his Hollywood films, the demands of directors and time schedules has sometimes forced him to experiment with technical gimmicks. He steered away from them in Bergman films, however, relying instead on a dogged determination to wait until the natural light was right to shoot. One exception to this is Bergman's fantasy The Magic Flute , shot in a studio, in which Nykvist used a good many colored filler and key lights and a strong backlight rather than his usual bounce lighting; yet he still preferred to manipulate the light rather than use extensive lab work or distorting lenses and filters. More typical of his style is his bravura camerawork on Scenes from a Marriage , which included ten-minute takes with as many as 20 zooms per take, plus complex camera movements. His ability to track an actor precisely and sensitively during a long take is phenomenal, and most of Scenes from a Marriage was shot with only one camera, held, of course, by Nykvist. Despite his technical mastery and careful preplanning, he relies heavily on instinct and a feel for shots, and approaches his work more as an artist than a technician.

For decades, foreign cinematographers had little chance of working in American films. The easing of union regulations in the 1970s, however, allowed European directors of photography an increasing visibility in the American film industry. Since then, Nykvist has photographed a variety of American films, from Agnes of God to What's Eating Gilbert Grape. And over the years, he has worked for other filmmakers, including Louis Malle, Roman Polanski, Andrei Tarkovsky, Volker Schlöndorff, Philip Kaufman, Lasse Hallstrom, Nora Ephron, Liv Ullmann (in which he maintained his Bergman connection), and Woody Allen, and directed his own films. Particularly notable is his work with Allen on Another Woman, Crimes and Misdemeanors, Celebrity , and the "Oedipus Wrecks" episode of New York Stories. But Nykvist still remains synonymous with Ingmar Bergman, with their collaboration producing the cinematographer's most innovative, influential, and renowned work. In Light Keeps Me Company , a documentary directed by Nykvist's son, Carl-Gustav, Bergman noted, "Sven and I saw things alike, thought things alike; our feeling for light was the same. We had the same basic moral positions about camera placement."

—Patricia Ferrara, updated by Rob Edelman

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: